The Smoke and What Follows

The bodies won't stand.

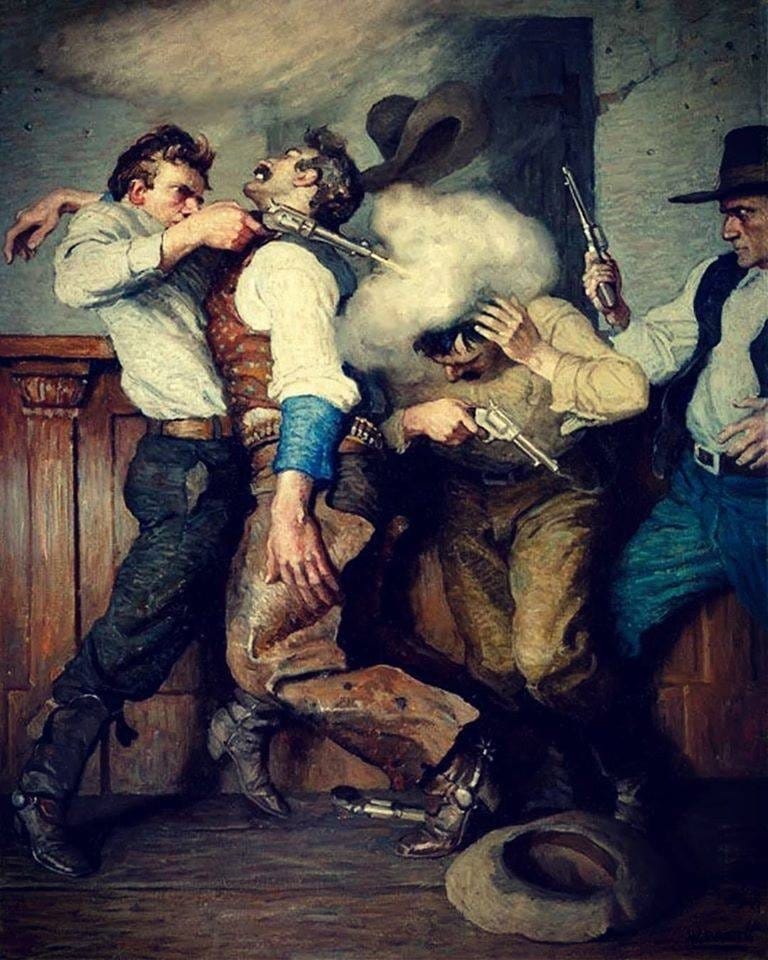

In N.C. Wyeth's Gunfight, painted in 1916, four men occupy a saloon interior in what should be a moment of Western heroism. But there's no clear geometry to the violence. No upright victor. One man's knees are already buckling. Another has his arm wrapped around an opponent's neck, not in control but in mutual collapse. A hat has come off—not dramatically flung but simply gone, the way objects leave hands when hands stop being instruments of will. The pistols are firing, smoke fills the middle distance, but what the smoke does isn't dramatize. It erases. It interrupts sightlines. Behind it, a fourth figure watches from a doorway, his role in the scene as illegible as everyone else's.

What's striking isn't the action but the absence of readable force. The bodies aren't opposing each other along clean vectors. They're interpenetrating—slumped, folded, grabbing at each other in ways that make it impossible to say who's winning. The painting has a staged quality, the composition of an illustrator trying to create narrative clarity. But the bodies betray that intent. They refuse heroic posture. What's left is something more like anatomy: flesh under pressure, limbs becoming liabilities, men in configurations that violate the upright masculine form we associate with agency.

There's an almost boneless quality to the tangle of bodies, a physical intimacy that resembles nothing so much as Tom of Finland's homoerotic drawings—not in content but in structure. Both depict male bodies stripped of autonomous control, rendered through contact and constraint rather than individual posture. Tom of Finland eroticizes this loss of sovereignty. Wyeth may have been attempting pulp adventure, but what the painting actually documents is the collapse of the very grammar it's trying to use.

The date matters. 1916. Wyeth painted this romanticized Western gunfight while Verdun and the Somme were in their second year. While European trenches were demonstrating what violence actually looked like at industrial scale: anonymous, mechanized, bodies disappearing into mud. Wyeth was clinging to nineteenth-century mythology—individuated combat, legible adversaries, conflict that could be narrativized at the scale of bodies-with-agency. History was already demonstrating that this grammar had collapsed. The painting is less wrong than anachronistic, reaching for a structure of violence that was being actively invalidated elsewhere.

But even attempting to paint that old structure, Wyeth couldn't make it work. The bodies insisted on something else.

I knew Austin Thomerson as a friend-of-a-friend, a "guitar guy" and a "2A guy" I'd never met. He was killed in November 2019 during an armed robbery at a pawn shop on Bellaire Boulevard in Houston. Two masked men entered around 7:50 PM. Thomerson, who was also armed and had a concealed carry license, intervened. He was shot multiple times and pronounced dead at the hospital. One suspect was arrested nine months later in Louisiana. At least two others remain unidentified.

The news reports provide these facts. What they don't provide—what they can't provide—is anything about the seconds when it happened. What Thomerson saw when the door opened. What assessment he made about the employees, one or both of whom he likely knew. Whether he drew first or was responding to weapons already aimed. Where everyone was positioned. How much time elapsed between the robbers entering and shots being fired. The surveillance video exists but has not been released publicly.

What I know is this: Thomerson frequented pawn shops across Houston looking for guitars. According to a friend interviewed after his death, "That's really the main reason he carried a gun was that he knew that those were dangerous, could be dangerous situations, and he wanted to be prepared as he could for something like that to happen." This wasn't impulsive heroism. This was someone who had thought about risk, made a calculated decision about environments he chose to enter regularly, and carried accordingly.

He died anyway.

Not because he was untrained—I don't know his training background beyond the license requirement. Not because he made an obvious tactical error—I don't have access to positioning, timing, or sequence. Not because intervention is inherently wrong—I don't know if the employees were in immediate mortal danger. What happened in those seconds is inaccessible to me, and largely inaccessible to public discourse. What we have is aftermath: bodies, ballistics, arrest records, news coverage, and five years of people like me writing about what it means.

That conversion—from event to meaning—happens fast. In gun culture forums, Thomerson becomes a case study. Active Self Protection channels might analyze the surveillance footage frame by frame, extracting tactical lessons: positioning errors, initiative disadvantage, the problem of drawing on drawn guns. In gun control discourse, he becomes evidence that "good guys with guns" don't stop crime. On social media, he's reduced to comment-section shorthand: "Poor bastard," "Should've been a witness," "Died protecting others," "Proof that training matters," "Proof that it doesn't."

Everyone wants the death to mean something. To yield transferable knowledge. To prove a point. Stalin supposedly said that one death is a tragedy, a million deaths a statistic. Social media inverts this: one death becomes a statistic immediately—deployed, weaponized, converted into data supporting whatever framework the speaker already held. The individual dissolves into argument.

I'm trying not to do that.

Around the time Thomerson was killed, I was training at the Clackamas County Sheriff's Public Safety Training Center outside Portland. I'd completed the basic handgun course, the concealed carry class, and was practicing toward the next level—trying to consistently place shots in three-inch groups at seven yards. The instructor told me that was roughly the baseline for advancing.

The training is good. The facility is professional. The curriculum is designed for measurable outcomes: students who can safely handle firearms, place accurate shots, understand use-of-force law. After decades of operation, the center has maintained zero negligent discharges in civilian courses. This is an accomplishment. It means the system works for what it's designed to do.

What it's not designed to do—what no institutional training can do without destroying its own pedagogical function—is simulate the actual phenomenology of a defensive encounter. In one class I assisted, I said off-handedly: "It's ludicrously easy to shoot someone, and it's infinitely harder to do so as an armed citizen who will be held to account for every shot fired." The first part is mechanically true. Students who have never touched a gun can, within hours, place twelve rounds in the A-zone of a target at various distances without safety violations. The second part is about everything that happens after—the legal scrutiny, the civil liability, the moral weight, the years of processing that follow seconds of action.

In February 2020, I did my first IDPA competition. One stage simulated a pawn shop robbery—half a dozen cardboard bad guys. They didn't shoot back. Later, I did a video simulator scenario at a local range: a convenience store holdup with a second assailant sneaking in from the side. You could see him in the security mirror. The mirror existed for pedagogical reasons. It preserved legibility. It made the scenario teachable.

Real violence doesn't annotate itself. It doesn't provide mirrors or telegraphed entrances. And the cardboard never shoots back.

This isn't a criticism of training. Training produces genuine competency within bounded systems. Students learn weapon manipulation, sight alignment, trigger control, malfunction clearance. They internalize safety protocols. They study use-of-force law. All of this matters. All of this improves outcomes in many defensive situations.

But training operates in a domain where variables are controlled so they can be taught. The range maintains clear firing lines, known distances, predictable target behavior. Even "stress inoculation" drills—shoot-and-move exercises, timed strings, competitive pressure—are bounded by the fact that everyone goes home afterward. The simulator can introduce complexity, but only complexity that remains legible enough to debrief. The mirror shows the second threat because without that affordance, the scenario becomes unteachable.

What training cannot simulate without ceasing to be training is the zone where those bounds dissolve: multiple armed adversaries with initiative advantage, positioning you didn't choose, incomplete information processed under time compression that precludes deliberation, and consequences that are immediate and irreversible. Not because instructors are incompetent, but because making that zone fully representable would destroy the institutional structure that makes learning possible.

We want lessons. We want transferable knowledge. We want to believe that with sufficient preparation, the gap between range performance and lived violence can be closed. This is human and reasonable. It's also a kind of comfort-seeking.

The thing about the Wyeth painting that a 2009 blogger missed—the thing that makes it useful here—is that it accidentally documents what it was trying to mythologize. The blogger, an illustrator himself, praised the painting's composition: "It brings you into the fight, into the adventure, and does what a good illustration ought to do. It makes you want to finish the story."

But I don't want to finish the story. I want to stay in the moment the painting can't help but show: the moment when bodies stop being protagonists and become just bodies, when the smoke obscures rather than clarifies, when the clean geometry of heroism collapses into something that more closely resembles mutual catastrophe than victory.

That's the moment training can't reach. Not because training is inadequate, but because the moment itself resists the frameworks we use to make it legible.

Here's the sequence:

First: violence.

Then: accounting.

During the violence—during the boneless tangle of bodies, the smoke, the seconds when outcome remains undetermined—there are no moral categories operating. There's only momentum, mass, positioning, timing, and whatever processing the nervous system can accomplish under conditions of extreme compression. No justice. No lessons. No roles. Just physics and flesh and incomplete information.

When the smoke clears, accounting begins.

Bodies get tagged: victim, perpetrator, armed citizen, bystander. District attorneys decide whether to charge. Grand juries determine if force was justified. Civil attorneys assess liability. News coverage assigns narrative roles. Social media converts the incident into data points. The gun community extracts tactical lessons. Policy advocates deploy the case as evidence. Families grieve whatever category their person got assigned.

The accounting is inexorable and extends indefinitely. Thomerson's decision and action occurred within seconds. The processing—legal, social, moral, tactical—continues five years later. One suspect arrested nine months after the event. Others still unidentified. This essay written half a decade later. The asymmetry is absolute: seconds of violence, years of accounting.

What justice cannot access is the phenomenology of the event itself. What Thomerson saw and assessed in real time. Whether the employees were in immediate danger. Whether drawing was tactical error or moral necessity or both or neither. Even if the surveillance video were released, it would only provide surrogate legibility—a view from camera position, time-stamped and reviewable. Not the experience of being inside the event when outcome was still undetermined and categories had not yet formed.

This is not an argument against intervention. Thomerson made his choice with available information in circumstances I cannot reconstruct. It's not an argument against training—preparation improves outcomes in many encounters, and Thomerson chose to prepare specifically because he'd assessed the risk of the environments he frequented.

It's just an acknowledgment: there exists a zone where the frameworks we use to think about violence—legal, tactical, moral—may not survive contact with the thing itself. And no amount of preparation guarantees they will.

Not because preparation is futile. Because the zone is real.

Honest discussion of armed citizenship requires admitting that no framework fully survives contact with lived violence, and that pretending otherwise is comfort-seeking. Not malice. Not propaganda. Comfort.

The Wyeth painting as romantic adventure. The range curriculum with its measurable outcomes. The simulator mirror that telegraphs the second threat. The IDPA cardboard that doesn't return fire. The Active Self Protection frame-by-frame analysis. The statistical arguments about defensive gun use prevalence. The social media conversion of individual deaths into immediate argumentation.

All of these are comfort technologies. They make violence legible, extractable, teachable, deployable. They are necessary for instruction, for law, for social functioning, for political discourse. But they are not the thing itself.

They are what we build after the smoke clears.

The bodies in Wyeth's painting remain tangled. One man's knees are buckling. The smoke obscures the middle distance. A hat lies on the floor. Someone in the doorway watches, his role unclear.

Then the painting ends, and we—viewers, critics, bloggers, essayists—begin the work of saying what it means.

But during the moment Wyeth tried to capture, before accounting could begin, there were just bodies doing what bodies do when projectiles are involved and control has been lost. No heroes. No villains. No lessons yet.

Just the smoke, and what it hides, and what follows after.