The Dungeon as Mirror: A Systems Theory of Bounded Play

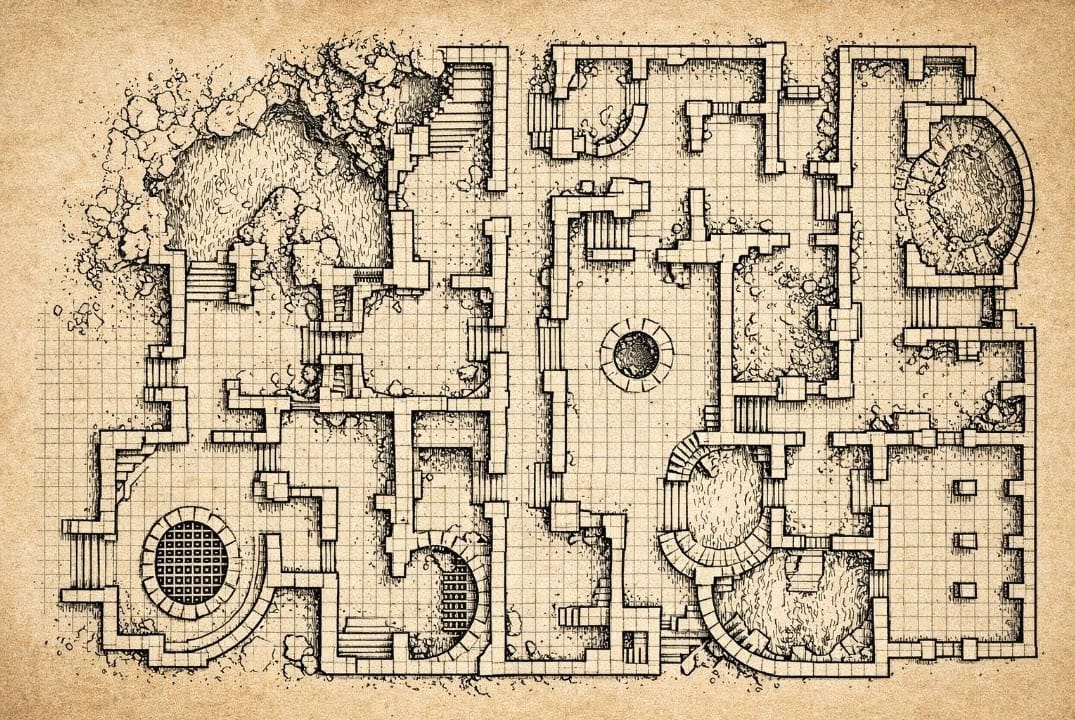

It started with a dungeon map—corridors branching into chambers, chokepoints narrowing into passages, the whole thing rendered in that particular style of competent anonymity that machine learning produces so effortlessly.

I. The Map Without a Key

The image appeared in a Facebook group dedicated to AI-generated art. It could have been a tomb. It could have been a sewer. It could have been the basement of a particularly ambitious wizard.

What it was, in the most literal sense, was geometry. Constraint made visible. A skeleton of friction waiting for flesh.

The question that surfaced wasn't "what monsters live here?" or "where's the treasure?" Those are the questions dungeon maps are supposed to provoke. Instead, the question was stranger: What else could this be?

Not a ruin. Not a crypt. Not the lair of something that needed slaying. What if the same corridors and chambers belonged to a civic archive? A transit interchange? A hospital wing sealed mid-operation? A regional tax authority?

The moment you ask that question, something shifts. The dungeon stops being a genre artifact and becomes a system—a bounded structure that exists to do work. And once you see it that way, you can't unsee it.

II. The Job to Be Done

Every dungeon, whether drawn on graph paper in 1974 or generated by neural networks in 2024, answers the same implicit question: What is the work to be done here?

The traditional answer is simple: the dungeon exists to be explored, looted, and survived. Players want portable advantage—gold, magic items, experience points—and the dungeon exists to make that acquisition non-trivial. Rooms are friction. Monsters are quality control. Traps are loss functions. The whole apparatus converts risk and coordination effort into future optionality.

This is not metaphor. It is mechanism.

Gary Gygax, whether he knew it or not, built a cybernetic system. The dungeon resists. It adapts (through restocking). It maintains homeostasis (through wandering monsters that punish dawdling). It has feedback loops and failure modes. It does work.

Stafford Beer, the management cybernetician who gave us the Viable System Model and the aphorism "the purpose of a system is what it does," would have recognized the dungeon immediately. Not as fantasy. As diagnosis.

III. The Portability of Value

Here is where the analysis sharpens into something uncomfortable.

Classic Dungeons & Dragons had a specific economic contract: the rewards were portable. Gold traveled. Magic items traveled. Experience points compounded into capabilities that functioned outside the dungeon. You could leave richer than you entered, and "richer" meant something in the world beyond the dungeon's walls.

This matters more than it appears to.

A system that produces portable value is a system you can exit. The dungeon might kill you, but if you survive, you take something with you. The friction was real, but so was the payoff. The conversion rate between danger and advantage was legible and fair.

Now consider what happened when dungeons went digital.

The first computer RPGs tried to preserve this contract. Grid-based movement, fog of war, resource attrition, lethal mistakes—these were attempts to emulate tabletop uncertainty in a deterministic medium. But the machine quietly changed the deal. Rules became authoritative rather than negotiated. Outcomes became certain rather than argued. The dungeon stopped being a conversation and became a verdict.

Then came the action RPGs, and the dungeon's job shifted again. Now it existed to deliver enemies at pace, sustain flow state, and emit loot continuously. Constraint moved from decision-making to execution speed. Death became a time tax rather than an existential event. The dungeon became a slot machine corridor—and it worked brilliantly, for that mode of play.

Then came the MMORPGs, and the contract changed entirely.

IV. The Dungeon as Service

In World of Warcraft and its descendants, the dungeon is not a place in the world. It is a queue endpoint. It has known rewards, known difficulty bands, known completion times. It is instanced, repeatable, role-legible, and failure-tolerant.

Its job is no longer conversion of risk into portable advantage.

Its job is retention.

The rewards in an MMORPG dungeon are carefully calibrated to function only inside the system. Gear scores matter only in the next dungeon. Currencies buy upgrades that enable harder content that drops better currencies. The loop closes. Value stops being portable and becomes positional—meaningful only relative to other players, other content, other metrics internal to the game.

This is not a criticism. It is a description of a business model. Systems that scale cannot afford to let value escape. Every piece of portable advantage is a reason to stop playing. The dungeon must therefore produce rewards that require continued presence to matter.

The player doesn't leave richer.

The player leaves viable—for the next session.

V. Dungeon Keeper and the View from the Control Room

In 1997, Bullfrog Productions released Dungeon Keeper, a game that inverted the camera. Instead of playing the adventurers, you played the dungeon's operator. You dug corridors, placed traps, recruited monsters, and managed the logistics of evil.

It was very funny. It was also, quietly, a management simulator.

The dungeon in Dungeon Keeper is still a bounded system converting effort into value. The inputs just changed. Instead of player skill and risk tolerance, the inputs are gold, space, labor, and time. Instead of adventurers extracting treasure, adventurers are environmental hazards—load spikes that stress-test your infrastructure.

And here is the reveal that the game makes explicit:

The dungeon must continue.

There is no win state where you say, "The dungeon has fulfilled its purpose. Let's shut it down responsibly." That option doesn't exist. Growth is mandatory. Expansion is survival. Stagnation is vulnerability.

You are not playing a villain.

You are playing a middle manager in a system optimized for its own perpetuation.

VI. The Triad of Outcomes

Once you recognize that some dungeons (and some institutions) are optimized for continuation rather than completion, a troubling pattern emerges.

When you engage seriously with such a system, there are only a few stable outcomes—attractors toward which trajectories tend to flow, though not the only destinations possible:

You are slain by the monster. This is failure in the literal sense. In dungeon terms, you die or retreat. In institutional terms, you burn out, are expelled, or are quietly broken. The system doesn't need to hate you for this to happen. It just needs to apply pressure consistently.

You live with the monster. This is accommodation. You don't approve, exactly, but you adapt. You learn which fights aren't worth having. You internalize the constraints as "how things are." The monster remains. You just stop charging it.

You become the monster. This is absorption. You don't just adapt—you are recruited into continuity. You start enforcing rules you once questioned. You justify actions in the system's language. You measure success by the system's metrics because those are the only ones that count.

Systems can also be mutated, parasitized, symbiosed with, or terminated. But in systems designed for continuation, the triad represents the states toward which most trajectories bend—which is why they feel inevitable from the inside, even when they are not.

VII. The Overlook Hotel Problem

In Stephen King's The Shining, the Overlook Hotel is not a haunted house in the simple sense. It is a self-stabilizing institution.

It doesn't attack you. It hosts you. It accommodates your presence. It offers you a job, a purpose, a role in its continued operation. Jack Torrance doesn't get possessed so much as promoted.

This is the nightmare scenario for anyone who enters a system believing they can change it from within.

The Overlook doesn't need to stop interventionists. It just needs to absorb them into its operating rhythm. You came to manage it; you become maintenance. You came to understand it; you become an archivist. You came to disrupt it; you become an enforcer of continuity.

The system doesn't trap you with bars.

It traps you with responsibility.

You stay because the boiler needs watching. Because the books need balancing. Because the place would fall apart without you.

Congratulations. You are now indispensable to something that should probably not exist.

VIII. What Kind of Theory Is This?

At this point, a clarification is necessary.

What has been developed here is not a universal ontology of play. It is not a claim that all dungeons work this way, or that all games are secretly capitalist, or that fun is an illusion masking exploitation.

This is a failure-oriented systems diagnostic.

It works best when applied to systems optimized for continuation, systems that obscure their exit conditions, systems where success metrics are endogenous. It explains why MMORPG dungeons feel different from tabletop ones, why Dungeon Keeper is secretly a management sim, and why institutional reform so often fails.

It does not explain gift economies, ritual play, pastoral games, or experiences that are valuable precisely because they don't scale. Some dungeons are not mirrors or rehearsals at all—they are playgrounds, and their value lies in being forgotten. The framework has no purchase there, and that is as it should be.

The thesis is forensic, not taxonomic. It tells you how certain dungeons go wrong—not what all dungeons are.

IX. The Value Trichotomy

To make the analysis precise, we need a sharper definition of value.

Value is that which allows the agent to reduce future constraint, either inside or outside the system.

This gives us three useful distinctions:

Internal value reduces constraint within the system. Gear score, access, authority, reputation inside the dungeon—these matter only as long as you keep playing.

External value reduces constraint after exit. Gold, skills, stories, relationships, changed conditions—these travel with you when you leave.

Terminal value ends the relevance of the system entirely. Closure, sufficiency, collapse, walking away—these make the question of "winning" moot.

Classic D&D prioritized external value. MMORPGs prioritize internal value. Games like MÖRK BORG often offer terminal value: the experience ends the question rather than answering it.

And Intervention Mode—the attempt to change what a system does rather than merely survive it—becomes legible as a fight over where value points.

Systems that absorb intervention do so by converting external and terminal value claims into internal value rewards. "You want to change things? Here's a promotion. Here's access. Here's influence—inside the system, where it counts." The committee seat, the title, the access badge: these are the coins of telos inversion, where the system's means quietly become its ends.

The reformer becomes the administrator.

The revolutionary becomes the bureaucrat.

The dungeon continues.

X. The Counterexample: Systems That Persist Without Devouring

Not every bounded system that endures becomes an Overlook. The difference lies in a single design principle: external telos with recognized sufficiency.

A system oriented toward something beyond itself—and capable of treating "enough" as success—resists the drift toward self-perpetuation. It can persist without devouring because continuation is a means, not an end.

Consider the volunteer fire department in a small town. It is bounded (membership, jurisdiction, resources). It persists across generations. It converts effort into value (safety, community, competence). But its success is measured not by its own continuation but by the absence of catastrophe in the community it serves. When there are no fires, the department has succeeded—even though it has produced nothing internal to show for it.

This doesn't mean such systems are immune to pathology. Volunteer organizations have politics; people burn out; "we need you" can become its own trap. But these systems are less able to absorb reformers into administrators, because they lack the resources and because their purpose keeps pointing outward.

The same logic applies to certain libraries, mutual aid networks, and open-source projects maintained by small groups who explicitly refuse to scale. These are fragile systems. They persist through commitment rather than incentive. And crucially, they define sufficiency as a valid outcome.

The diagnostic framework developed here applies to systems that have inverted their telos—systems where continuation has become the purpose rather than the means. The volunteer fire department reminds us that bounded systems can persist without becoming traps, provided they remain oriented toward something beyond themselves.

This is not a loophole. It is a design principle.

XI. Rehearsal and Performance

There is, however, an escape clause even for systems that have begun to drift.

Dungeons can function as rehearsals—spaces where you practice decision-making under pressure, explore power fantasies safely, test coordination and trust and risk tolerance. A rehearsal is bounded, iterative, forgiving, and inward-facing. You learn the chords. You get tight. You stop when you're tired.

But a rehearsal only matters if there is a performance.

A gig is public, time-bounded, fragile, exposed to judgment, and followed by dispersal. Crucially: you don't live at the venue. You show up. You play. You leave. The night ends.

A dungeon functions as rehearsal only if it produces something portable:

- Portable skill: judgment, coordination, risk sense

- Portable narrative: stories that reframe identity or possibility

- Portable relationships: trust, solidarity, shared language

- Portable confidence: "we've done something like this before"

- Portable clarity: knowing what you will not tolerate again

A dungeon fails as rehearsal when success requires permanent presence, when competence only works inside the system, when meaning collapses on exit, when growth is the only form of validation.

That is the Overlook failure mode. That is telos inversion made habitable.

A good rehearsal tightens the set, surfaces failure safely, ends on time, and leaves you hungry to play elsewhere.

A bad rehearsal never ends, confuses preparation with purpose, replaces gigs with optimization, and quietly becomes the band's entire world.

XII. The Design Question

All of which brings us to the question that matters—not for game designers only, but for anyone who finds themselves inside a bounded system that seems to demand continued presence.

The question is not: Can you beat the dungeon?

The question is: Does this experience teach you how to leave?

A system that teaches you how to leave is a system that produces external or terminal value. It gives you something you can take with you. It has an ending that is not failure. It treats sufficiency as a valid outcome.

A system that prevents you from learning how to leave is a system optimized for its own continuation. It converts your effort into internal value. It makes exit feel like loss. It offers you responsibility instead of freedom.

The most dangerous dungeon is not the one that kills you.

It is the one that convinces you there's nowhere else worth playing.

XIII. The Mirror and the Door

It started with a dungeon map, generated by AI, aesthetically competent, and fungible in almost every functional way.

It ended with a question about institutions, absorption, and the conditions under which bounded systems become traps.

The connection is not metaphorical. The dungeon is a bounded system that converts effort under constraint into value. So is a corporation. So is a platform. So is a career. So is any structure that asks for your presence and offers rewards calibrated to keep you present.

The difference between a dungeon and a trap is not danger. Danger can be survived, learned from, even enjoyed.

The difference is exit.

A dungeon with a door you remember is a challenge. A dungeon that makes you forget there ever was a door is something else: a home you never chose, maintained by labor you no longer question, in service of purposes you can no longer name.

The map is just geometry. The key is knowing you came in through a door—and that the door still exists, even when the system would prefer you forget.

The mirror can be walked away from.

But only if you remember it was never meant to be a house.

The dungeon awaits. The question is whether you're entering to play—or to stay.