The Constitutional Turducken

Or, The Right To Bear Arms And Why We Can't Have Nice Things

"Unfortunately, [the academics] agree because they are all studying the same part: the anus."

—David Yamane, sociologist of Gun Culture 2.0

I. Ambient

You pull into the lot fifteen minutes after opening. Already full. The cars gleam under November daylight like beetles arranged in perfect rows. You know this pattern. You've always known this pattern.

The gas pumps first. Ritual. You watch the numbers climb and your mind performs its own small ceremony—the spread between Chevron and here, the miles-per-gallon whispering back your week's movements. These calculations anchor you. They prove the machine beneath you still obeys physics. That something, at least, remains predictable.

Inside, the doors yawn open and you enter the hum.

Not music. Not crowd noise. Something underneath both. A frequency that lives in the concrete and fluorescent tubes. You don't fight it. You learned long ago to swim through sound rather than against it, moving between currents of shopping cart wheels, susurration of conversations and "where's Dad?," and the low thunder of the walls and ceilings respiring.

The aisles stretch longer than they should. Geometry bends here, though no one else seems to notice. A woman stands perfectly still before a monument to bulk olive oil, her face slack, eyes fixed on a point six inches beyond the bottles. You give her distance. Some people get caught in the undertow.

You navigate by ear. The scrape of a cart's bad wheel tells you someone's approaching from your six. A child's rising whine becomes a waypoint. The sudden silence near the rotisserie chickens means a cluster has formed, a congregation you'll route around without conscious thought.

Then you see him.

The man with the flatbed cart. Two dozen pumpkin pies stacked like some offering to a god of abundance and mathematics. You think: more pi than a geometry class. The joke arrives unbidden, a small bright coin your mind tosses up to keep the darkness at bay. Eyes connect, nods exchanged. Molecules bounce, inert.

At the checkout, a parent marshals three children and an overflowing cart. Their hands move in practiced patterns—cereal box, juice container, bulk paper towels—each item a small negotiation with chaos. You watch and think: That's me in another timeline. The thought doesn't hurt. It simply is, like a frequency you can suddenly hear but have always been there.

The food court seethes. Too many bodies. Too much want concentrated in too small a space. The $1.50 hot dog, your usual reward for completing the consumerist speed run, will have to wait. Will have to remain theoretical. You turn toward the exit instead.

Outside, the daylight feels thin, unconvincing.

You load the car. Fifteen pounds of brown rice, four pounds of tofu, two jars of marinara, and so on. At least eight meals accounted for. Two hundred dollars translated into continuity, into future moments when you won't have to decide, won't have to scramble. The math grounds you the way the gas pump math did. Small ceremonies against randomness.

Driving home, you think about the word petty. How it shrinks harm until it can be carried by someone else. How random does the same—transforms presence into absence, specificity into atmosphere. But you were there. Your body moved through that space. Nothing was random because you were perceiving it. Nothing was petty because you felt its weight.

The rice in your trunk knows what those grains have always known: that we provision against the dark not because we can prevent it, but because the act itself—the choosing, the carrying, the storing away—makes us human-sized again. Makes the world something we can touch.

You've been doing this longer than you care to admit. The calculations, the ear-navigation, the small bright coins. It's not paranoia when local businesses close due to "petty theft" and "random violence." When the MAX station actually does have a memorial to murder victims. When "this is just another day" is something a neighbor actually says about a parking garage shooting. The grief isn't sharp anymore. It's the hum rhyming with the road noise—always there, barely noticed, part of the infrastructure.

On the right, you pass the Grocery Outlet that made the news last week. The owners considering shutting down the store, because the staff feel unsafe. An understatement considering how people have been stabbed and menaced with guns over pastries. On the other side of the street is the gastropub you'd been thinking of trying at some point. Further down the road is where the hustlers would walk in the summer months, clad in string bikinis or too-short shorts.

You pull into your driveway.

The engine ticks as it cools.

The unloading starts.

A couple of miles from here, in a parking garage behind a 24-hour gym, someone's blood has already been washed away. A stone's throw from that garage, a MAX train pulls into a station where men once fell, stabbed to death for intervening in a racist haranguing. The city holds these moments in its concrete the way your body carries over the frequency of the warehouse.

You carry your provisions inside.

Random. Petty. The words dissolve like breath in pre-winter air.

You were there. That changes everything. And nothing.

II. The Sorting Mechanism

Three days earlier, I stood in a different kind of sorting mechanism.

The Multnomah County Courthouse opens at 7:30 AM. I arrived at 6:45, having paid twenty dollars to Uber to avoid the bus. The institution kept its own hours. No explanations provided.

When the doors finally opened, I entered a jury assembly room that resembled a terminal for departures to unspecified destinations. Rows of seats bolted to floors. A large screen displaying names, courtroom numbers, times. I had entered a sorting mechanism.

I'd been summoned twice before, both times in Houston, more than a decade past. The first time: waiting, dismissal, a taqueria meal, a cute dog spotted through a car window. The second time: summer heat, a criminal case involving a truck driver and a traffic violation. The evidence consisted of an officer's statement. I, aggregated with eleven others, voted guilty. The decision took minutes. The mechanism accepted the input and produced its output. The truck driver's name was forgotten, along with his offense.

This time I understood more about the machine. Not enough to refuse entry—one simply does not refuse—but enough to observe with greater attention.

By Day Three, I was Juror 37 in a roster of forty. When the charges were read, I realized one of my red lines had been crossed. I made that clear to the judge, prosecutor, defense attorney, defendant, and the other thirty-nine panelists.

Then came the question: "Do you have strong opinions on guns?"

My hand went up.

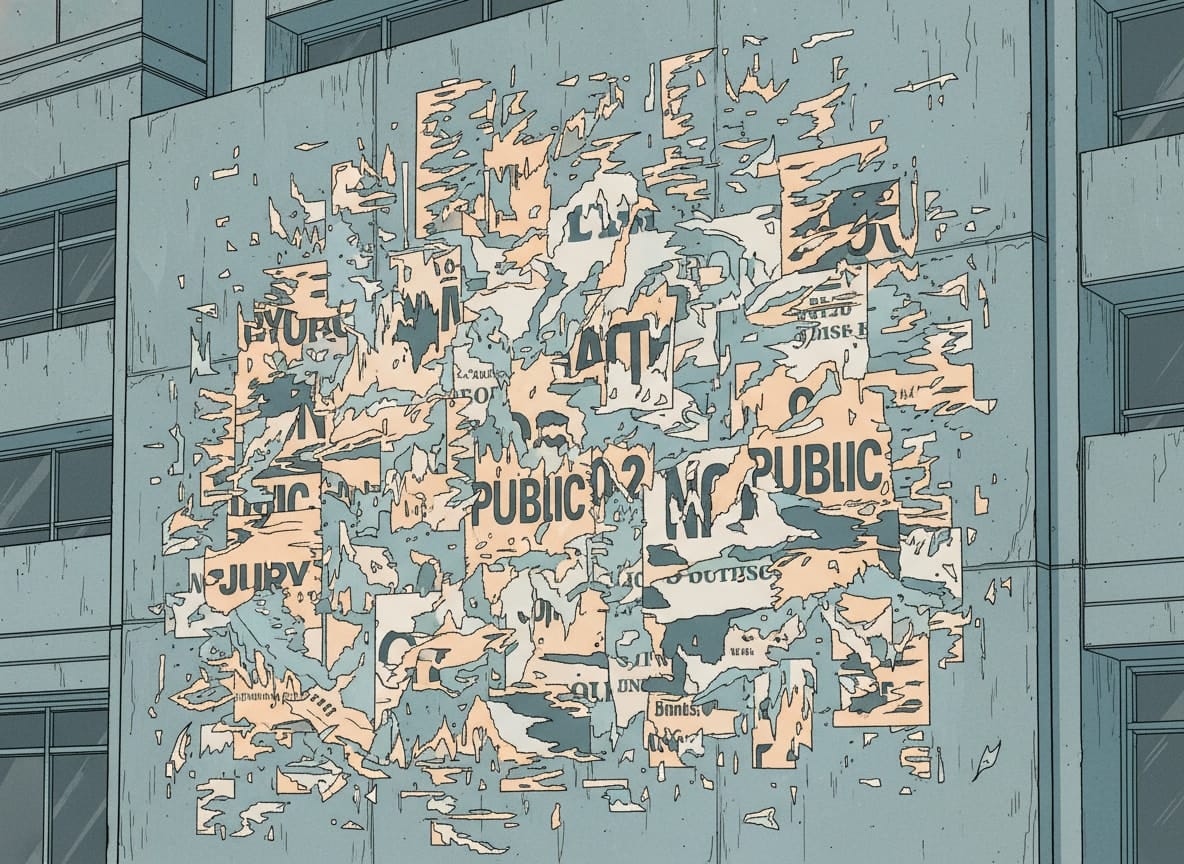

The phrase arrives before I can stop it: constitutional turducken. It's been sitting in my head for years—history, law, culture, violence, all compressed together like birds stuffed inside birds, impossible to separate, equally impossible to digest. Now it's about to come out of my mouth in a courtroom.

What followed was an unsolicited TED talk that the prosecutor mercifully cut short. But I'd already said enough:

The American debate on firearms isn't just complicated. It is incendiary. The Second Amendment on which the right of civilians to keep and bear arms is predicated is an unusual chimera of statements that binds citizens, weapons, and militias together with 18th-century legalese in a way that's either brilliant or monstrous depending on your perspective.

The Dred Scott decision that disenfranchised an entire population rests on the inflammatory pillar that Black citizens would be able to pack heat, no militias required. While that ruling was overturned, Heller made the decoupling precedent, while McDonald and Bruen further whittled a square peg to be forced into a round hole, with the National Firearms Act as a coat of lacquer by prohibiting automatic weapons and explosives.

I also mentioned that I volunteer as a range coach with the Clackamas County Sheriff's Office, teaching people not to be the next Alec Baldwin, because shooting someone is ludicrously easy while proper firearm handling requires training.

The defense attorney stopped his voir dire at juror #36. He was done. Perhaps he sensed that given the charges and the red line I'd articulated, I might be first in line with the nails and the hammer, impartiality be damned.

I could see it happening in real-time. The mental calculus: This one's too complicated. Too many edges. Democratic activist but gun rights advocate. Range coach but knows a murder victim. Understands Dred Scott and worked against gun control. He'll deliberate in six dimensions and we can't predict which one he'll prioritize. Not to mention that he's biased AF.

A short time later the remaining pool was dismissed. I had not been selected.

The mechanism needs molecules it can model. I'm a molecule that expresses depending on temperature, pressure, and what other molecules are in the chamber. Too volatile. Too reactive. Unable to sublimate cleanly into a simple verdict.

The machine was right to reject me. I would have been a disaster in that jury box—not just because I couldn't be fair, but because I couldn't be simple. And simplicity is what twelve-person deliberation requires. You can't spend three days unpacking constitutional turduckens when someone's liberty is at stake.

There's a tacit understanding that not getting picked for a jury is a form of "losing." You spent three days in service of the state, paid for transit and downtown parking, ate overpriced salads, floated in the fuel tank—and the machine rejected you.

But that's not losing. That's not winning either. It's the mechanism working as designed: identifying molecules too volatile for the reaction it needs. Some of us are too charged. Some of us are too candid. The machine can't use us, but it needed to test us first.

That is literally showing up, as a citizen should.

Sociologist David Yamane describes the academic study of guns as examining only one part of the elephant. In his "spicier take," delivered at an academic symposium in November 2025, he specified which part: the anus.

I got ejected from jury duty for touching too many parts at once: history, civil rights, personal trauma, professional training, political activism. The mechanism couldn't process that much complexity.

Neither can the paradigm.

Yamane identifies what he calls the "dominant paradigm" in gun studies today: "American gun culture is founded on settler colonialism, that it is racist, sexist, and homophobic in its historical foundations and remains so at its contemporary core. Because of this, it is aligned with right-wing politics and threatens to undermine civil society and democracy."

He's careful to note that the formation of this paradigm represents "real progress"—not because its conclusions are necessarily correct, but because having any paradigm at all allows for organized scholarly debate rather than scattered noise.

But paradigms are double-edged. They help organize complexity by filtering out noise. They also prevent researchers from recognizing assumptions that differ from their own.

Yamane's work is based on a different premise: that guns are normal and normal people use guns. This violates the paradigm's assumptions so thoroughly that he's frequently met with resistance to this language of normality.

I recognize this resistance. I felt it in the courtroom when I tried to explain that I teach gun safety and know a murder victim. That I worked against Oregon's Measure 114 as a Democratic Party activist. That I understand the Second Amendment's racist foundations and believe civil rights require armed self-defense for marginalized communities.

The sorting mechanism ejected me because I couldn't be simplified. The academic paradigm would do the same.

But the turducken doesn't care about academic paradigms or jury selection. It exists whether we can process it or not.

The turducken isn't just about the Second Amendment's syntax. It's about how everything—history, law, culture, economics, bodies—has compressed into a single improbable mass. You can't extract one bird without destroying the whole dish.

Let's examine the layers we've been eating for centuries.

III. The Six Layers

Layer One: The Text

"A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

This is where it starts: twenty-seven words of 18th-century grammar that nobody agrees on. Does the militia clause limit the right, or merely explain it? Are "the people" individual citizens or the collective body politic? What does "bear" mean—carry, or use in militia service? What arms? What infringement?

Yamane notes that paradigms organize complexity by focusing attention. The dominant paradigm focuses on the historical context: militias as instruments of settler colonialism and slave patrols. That focus is not wrong. But it renders other readings invisible—including the reading that animated the Reconstruction amendments, where Black citizens and Republicans argued that the Second Amendment should protect the right of freed slaves to arm themselves against white supremacist violence.

Both readings exist in the text. The turducken's outer layer contains both birds.

Layer Two: The History (Who Gets To Be Armed)

In 1857, the Supreme Court delivered the Dred Scott decision. Chief Justice Roger Taney wasn't arguing about whether the Second Amendment protected an individual right—he was assuming it did. The problem, in his view, was that citizenship would give Black people the right "to keep and carry arms wherever they went." This was listed among the "catastrophic, unthinkable consequences" of recognizing Black humanity.

The logic was explicit: Armed Black citizens were so unacceptable that denying them citizenship altogether was justified. Taney's fear of armed Black people was treated as self-evidently disqualifying.

This is the firearm pillar that the entire structure rests on: The right was individual. And it was racially exclusive by design.

This is the history the paradigm sees clearly. And it's correct to see it. The Second Amendment emerged from a world where:

- Armed white men = militia = civilization = citizenship

- Armed Black people = insurrection = existential threat

- Armed Native peoples = savagery = targets for extermination

- Armed women = category error, not even imagined

The question of who gets to be armed has always been the question of who gets to be fully human.

But the history doesn't end with exclusion.

The Reconstruction Congress (1866-1868) saw Dred Scott clearly and meant to reverse it. When they drafted the 14th Amendment, they explicitly intended to protect freedmen's right to keep and bear arms. Congressional debates referenced the Second Amendment repeatedly. Southern states were passing Black Codes to disarm freedmen—forbidding them to own guns, requiring expensive licenses, criminalizing possession. Congress designed the 14th Amendment to stop this.

Representative Samuel McKee of Kentucky argued that the freedmen needed constitutional protection because "the right to keep and bear arms" was being systematically denied to them. Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan insisted that the 14th Amendment would enforce "the personal rights guaranteed by the first eight amendments"—explicitly including the Second Amendment—against state infringement.

This wasn't abstract. It was tactical. Armed freedmen could defend themselves against Klan violence, resist re-enslavement, and exercise the citizenship that Dred Scott had denied them. The right to keep and bear arms was understood as essential to Black liberation.

When Justice Clarence Thomas wrote his concurrence in McDonald v. Chicago (2010)—the case that incorporated the Second Amendment against state governments—he quoted these Reconstruction debates extensively. The 14th Amendment, he argued, was designed to ensure that freedmen could exercise the same gun rights that Dred Scott had denied them. The Second Amendment became national law specifically to protect Black citizens from disarmament.

This is the civil rights argument for gun access. And it's historically accurate.

It's also incomplete.

Because in 2021, in Massachusetts—which has both a magazine ban and a firearms licensing requirement—Black persons were charged with firearm offenses at 8.3 times the rate of white persons. Carrying a firearm without a license (the exact offense the 14th Amendment was meant to prevent): 7.5x disparity. Possession of a large-capacity magazine: 29% of charges against Black defendants, who comprise 12.4% of the state's population. Possession of ammunition without the proper license: 9.6x disparity.

These aren't accidents. They're patterns. The same patterns appear in Oregon, where I live. The same patterns would have appeared under Measure 114, Oregon's 2022 ballot measure requiring permits to purchase firearms—which is why I opposed it.

The 14th Amendment was meant to arm Black citizens. Modern enforcement disarms them—or more accurately, criminalizes them for being armed. Taney's nightmare came true: Black citizens got the right to keep and carry arms. Then we built an enforcement regime that arrests them for exercising it at eight times the rate of white citizens.

When California passed the Mulford Act in 1967, banning open carry, it was a direct response to Black Panthers legally carrying rifles while cop-watching in Oakland. Ronald Reagan, then governor, said: "There's no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying loaded weapons."

He meant Black citizens. Armed white citizens remained unproblematic.

You can't extract the racism from the civil rights argument. You can't separate the exclusion from the liberation. You can't untangle Dred Scott from the 14th Amendment from the Mulford Act from the Massachusetts data.

The question of who gets to be armed is simultaneously:

- A tool of white supremacy (Dred Scott)

- A tool of Black liberation (Reconstruction)

- A tool of racist enforcement (Mulford Act, Massachusetts)

- A civil rights issue (14th Amendment history)

- An ongoing disparity (current data)

This is Layer 2 of the turducken. All of it's true. All of it's cooked together. None of it can be separated.

What the paradigm often misses: recognizing all of this at once. Gun control advocates point to Dred Scott and the Mulford Act—correctly. Gun rights advocates point to the 14th Amendment and Reconstruction—also correctly. But acknowledging that both histories are real means acknowledging that there's no clean policy solution that doesn't replicate one injustice while trying to fix another.

When I worked against Measure 114, I wasn't defending gun rights in the abstract. I was saying: "I've read the Massachusetts data. I know what permit requirements produce in practice. Black residents will be charged at 8.3 times the rate of white residents, just like they are in every other state with similar laws. The 14th Amendment was supposed to prevent this. We're about to do it anyway."

This is the same layer of the turducken. The racism and the civil rights argument aren't opposites. They're compressed together, inseparable, equally true, impossible to digest.

Layer Three: The Courts (Reinterpretation)

For most of American history, the Second Amendment barely mattered. The Supreme Court mentioned it in passing a few times, always in the context of militias. Then came District of Columbia v. Heller (2008).

Justice Scalia, writing for a 5-4 majority, performed a feat of legal archaeology. He dug through 18th-century texts to argue that the right to bear arms was always individual, that the militia clause was merely explanatory, "prefatory" rather than limiting. The right belonged to "the people," meaning individual citizens, for "lawful purposes," primarily self-defense in the home.

McDonald v. Chicago (2010) incorporated this right against state governments. New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022) established that gun regulations must be consistent with the nation's "historical tradition" of firearm regulation—a test that essentially requires judges to conduct historical seances, asking: "Would this law have been acceptable in 1791? How about 1868?"

Each decision stuffed a new bird inside the old one, claiming continuity while fundamentally changing the dish. The militia disappeared. Individual self-defense became paramount. "Historical tradition" became the test, even though "tradition" includes centuries of racist enforcement.

Think about what this means: a nation with 3D-printed guns, bump stocks, and 20-30 million AR-15s is being governed by legal tests that ask "what would James Madison think?" The Supreme Court has decided that the only legitimate gun regulations are ones that would have been acceptable to men who owned other human beings and believed women couldn't vote. This isn't conservative jurisprudence. It's historical cosplay with lethal consequences.

And it worked. The cultural shift that followed Bruen wasn't accidental. It was structural.

The paradigm sees this as judicial activism in service of right-wing politics. That's not wrong. But it misses how Heller also created space for civil rights arguments that had been impossible under the militia-centric reading. If the Second Amendment protects individual self-defense, then marginalized communities have a constitutional argument for armed resistance to state violence.

Both readings exist in the case law. Another layer of our mutant poultry loaf

Layer Four: The Culture (Normalization)

In May 2025, the newsletter Open Source Defense published an essay titled "Gun rights are winning and nobody has realized it."

Their evidence:

- Multi-decade polling trend toward support for gun rights, even among non-gun-owners

- Concealed carry laws expanding to all 50 states (shall-issue or permitless)

- Gun control groups retreating from "ban handguns" to "gun safety" messaging

- The AR-15 going from controversial tactical rifle to "just a rifle"

By November, they updated the thesis: "Gun rights are winning. Now everybody has realized it. That means this is when the real work starts."

The numbers are stark: We estimate that between 20 and 30 million AR-15-style rifles are in civilian hands. In 2021, 67.5% of rifles sold were AR-15s. Everything else—every AK variant, every bolt-action rifle, every .22 plinker—had to split the remaining 32.5%.

To put this in perspective: according to SEMA's most recent Vehicle Landscape Report, there are currently 16.1 million Ford F-Series pickups on the road in the United States. The F-150 has been America's bestselling vehicle for 47 consecutive years. Everyone knows what one looks like. They're infrastructure—ambient, unremarkable, everywhere.

There are more AR-15s in civilian hands than F-150s on American roads.

When something becomes more common than the most popular vehicle in the country, you can't call it a "fringe weapon" anymore. You can't treat it as exceptional. It's not just a "scary black gun" carried by "tacticool weekend warriors." It's the rifle. It's what people buy when they buy a rifle, the way they buy an F-150 when they buy a truck.

The F-150 is involved in thousands of fatal crashes every year. We don't ban F-150s. We don't require special permits to own one. We accept them as infrastructure, as tools that some people need and others want, as objects that are simultaneously useful and dangerous.

The AR-15 has achieved the same status. Whether that's good or bad depends entirely on whether you think the F-150 comparison is reassuring or horrifying.

Twenty-nine states now have permitless carry. The other twenty-one are shall-issue, meaning authorities must issue a permit if you meet objective criteria. The entire United States is at least shall-issue. May-issue—where authorities had discretion to deny permits—no longer exists after Bruen. Even Everytown for Gun Safety, the major gun control organization, now offers firearms training courses.

The paradigm interprets this as cultural threat—the normalization of violence, the arming of right-wing extremism, the undermining of civil society. That interpretation captures something real. But it misses how normalization works.

Yamane’s provocation—“Guns are normal and normal people use guns”—isn’t a political statement at all. It’s a statistical one. When 67.5% of rifles sold are AR-15s, the AR-15 is normal in the same way the Ford F-150 is normal: typical, ubiquitous, unremarkable in the marketplace.

And yet that marketplace is anything but unregulated. It exists inside a lattice of prohibitions on automatic fire, short barrels, destructive devices, armor-piercing ammunition, and a long history of defining which bodies are allowed to lawfully bear arms in the first place. Normality and regulation aren’t opposites here; they’re the two rails the system runs on.

The paradigm can’t process this without immediately reading pathology or false consciousness into it. But normal doesn’t mean good or healthy or harmonious. It simply means prevalent, embedded, taken for granted—a fact of the landscape, not a judgment about it.

The turducken has been fully cooked. Most people just haven't noticed the taste.

Layer Five: The Economics (Geographic Disparity)

What does normal looks like on the ground?

In rural Montana, permitless carry. Walk into a store with a visible holster, nobody blinks.

In New York City, a 12+ month ordeal to get a carry permit. Pay fees, take courses, get fingerprinted, justify your need, wait for bureaucratic processing, maybe get approved.

In Portland, Oregon—my city—the Hollywood District parking garage where someone was shot and killed on a Friday morning. The Grocery Outlet considering closure because staff have been stabbed and menaced with guns over pastries. The MAX train station where two men were stabbed to death for intervening when another passenger was harassing women.

This is the economic geography of gun saturation. Zip codes determine whether you swim in guns or never see one. Whether carry is unremarkable or unthinkable. Whether gun violence is ambient background noise or shocking aberration.

The paradigm sees this disparity as injustice—urban areas suffering the consequences of lax rural gun laws. That's not wrong. But it misses how the disparity also means that lived experience of guns varies so wildly that people literally cannot imagine each other's reality.

Someone in rural Montana cannot imagine needing permission to carry. Someone in Manhattan cannot imagine not needing permission. Both are living in normal, just different normals.

But the geographic disparity goes deeper than carry laws. Gun death isn't one phenomenon. It's several phenomena wearing the same statistical trenchcoat.

Chicago, 2023: 617 homicides. Victims overwhelmingly Black (78%), male (83%), young (median age 28). Deaths overwhelmingly by handgun, in public spaces—streets, alleys, parking lots. Guns overwhelmingly obtained through informal networks: straw purchases, thefts, loans from family or friends. The deaths generated headlines, vigils, activist campaigns. They became symbols in the national gun debate.

Montana, 2023: Gun deaths overwhelmingly suicide (82%). Victims overwhelmingly White (90%+), male (80%+), middle-aged or older (median age 45-55). Deaths overwhelmingly by rifle or shotgun, in private residences—bedrooms, garages, barns, trucks parked in empty fields. Guns overwhelmingly legally owned, often for decades. The deaths generated obituaries, not headlines. They became invisible in the national debate.

These aren't variations on a theme. They're structurally different crises that happen to use the same tool.

The dominant paradigm sees Chicago and correctly identifies: systemic racism, over-policing, economic abandonment, concentrated poverty, guns flowing through networks of desperation. All true. The gun is the mechanism of harm, but the causes run deeper.

When you apply that same lens to Montana, you get: economic collapse, opioid crisis, social isolation, healthcare deserts, the dissolution of community infrastructure. Also all true. The gun is still the mechanism. But suggesting gun control as the primary intervention feels like treating a symptom while the patient bleeds out from something else.

This creates a policy nightmare:

- Universal background checks might marginally reduce straw purchases in Chicago (and in neighboring states). They do nothing about the Montana grandfather who's owned his deer rifle for 40 years and decides tonight's the night.

- Safe storage laws might reduce the Chicago child who finds a gun in a nightstand. They do nothing about the intentional homicide in a parking garage or the Montana suicide in a barn.

- Assault weapon bans focus on AR-15s, which are statistically a tiny fraction of gun deaths.

Chicago homicides use handguns. Montana suicides use whatever's available—rifles, shotguns, doesn't matter.

- Red flag laws could theoretically address both, if implemented perfectly. But they require someone to notice warning signs and take action. In isolated rural communities, there's no one to notice. In urban contexts where calling police on your neighbor is unthinkable, there's no trust to act. Structurally difficult to deploy.

The geographic sorting shapes the politics:

Urban voters experience guns as ambient threat from strangers. They see gun control as common-sense safety regulation.

Rural voters experience guns as tools and inheritance. They see gun control as urban elites criminalizing their way of life.

Both are responding to their actual lived reality. The turducken is that these realities are incompatible but equally valid from within their respective contexts.

A Chicago activist sees guns as instruments of community destruction, tools that kill neighbors and children, objects that should require permits, registration, training, waiting periods—anything to slow the pipeline.

A Montana rancher sees guns as inheritance and autonomy, tools for hunting and self-reliance, objects that have been in the family for generations and never hurt anyone until Grandpa used one on himself.

Both have shaped their politics from direct experience. Both would find the other's position incomprehensible.

The paradigm calls this pathology. I call it Saturday.

Layer Six: The Consequences (Who Dies)

Anna worked as the manager of a local game store that two of my friends own. Her husband and father of their four kids shot her in the head. Twice.

I didn't know Anna outside the context of the shop. But when I heard the news, it felt as if a curtain had shut out the sky.

On November 21, 2025—two days after I was dismissed from jury duty—a man named Daniel Snegirev allegedly shot two people in the Hollywood District parking garage. One died. One survived. Snegirev was arrested at a Tigard hotel after an hours-long manhunt.

The three men knew each other. Nothing was taken. "This feels personal," said a family member.

And then there are the children. Yes, invoking dead kids is like using them as rhetorical human shields. But they're still there. And dead.

Firearms have been the leading cause of death for children and teens in the United States since 2020.

In 2023, there were 2,566 firearm-related deaths among ages 1–17. That's not accidents—though those happen too, about 5% of the total, when a child finds a gun in a nightstand or glove compartment. The majority is homicide (63%) and suicide (30%).

Most of these guns come from home. In 2.6 million U.S. homes with children, guns are stored unlocked and loaded. The suicide rate among youth with firearm access is triple those without. The homicide rate is driven by handguns passed informally from peers or family—no background check, no paperwork, just a loan or a straw purchase.

Federal law prohibits selling handguns to anyone under 21. But there's no federal minimum age for possessing a handgun after 18, and private sales require no background check. In January 2025, the 5th Circuit struck down even the dealer restriction for 18–20-year-olds, citing Bruen's "historical tradition" test. If the Supreme Court lets that stand, more states will follow.

This is what "20-30 million AR-15s" means on the ground: the guns don't stay locked up. They move through families, peer networks, cars, nightstands. They're accessible to people who legally can't buy them. And children die—not because we failed to pass laws, but because the laws we passed assumed the guns would stay where we put them.

They don't.

The dominant paradigm focuses relentlessly on consequences like these. That's appropriate. These consequences are real, devastating, irreversible.

What the paradigm struggles with: how to hold these consequences alongside the 20-30 million AR-15s that exist, the permitless carry in 29 states, the normalization that's already complete.

How do you hold Anna's murder alongside the fact that I teach gun safety at a sheriff's range?

How do you hold the Hollywood garage shooting alongside the civil rights argument for armed self-defense?

How do you hold "felon in possession of a firearm"—one of the most common gun charges—alongside the reality that prohibited persons keep getting guns anyway?

The paradigm wants to resolve this tension by saying: Ban more guns. Restrict more access. Make it harder.

The gun rights side wants to resolve it by saying: Arm more people. Train more citizens. Make self-defense easier.

I can't resolve it.

I can only teach people not to be Alec Baldwin while knowing that teaching safety doesn't prevent murder. I can only provision against the dark while knowing I can't prevent it. I can only show up for jury duty while knowing the mechanism will reject me for being too complex.

The turducken is indigestible. We've been eating it anyway.

IV. Teaching (Living the Paradox)

I volunteer at the Clackamas County Sheriff's Office public gun range. I'm a range coach. My job is to teach new shooters the basics: grip, stance, sight picture, trigger control, muzzle discipline.

I tell them: Shooting someone is ludicrously easy. Proper firearm handling requires training.

I teach them the four rules:

- Treat every gun as if it's loaded

- Never point the muzzle at anything you're not willing to destroy

- Keep your finger off the trigger until you're ready to fire

- Be sure of your target and what's beyond it

These rules don't prevent murder.

Let me be clear about what I do at that range: I'm teaching people how not to accidentally kill each other. How to handle a deadly tool without negligent discharge. How to be competent rather than dangerous.

What I'm not doing: preventing murder. Stopping domestic violence. Reducing parking garage confrontations. Making the Grocery Outlet safe.

Safety culture is real. Training reduces accidental deaths. But "accidental" is doing enormous work in that sentence. Anna wasn't killed by accident. Daniel Snegirev didn't accidentally shoot two people in a parking garage.

I teach the four rules knowing they’re powerless against intent. That’s the paradox I carry every day: I’m doing something genuinely useful that can’t touch the problem that lives in the human soul. To the dominant paradigm, that looks like complicity; to the gun-rights movement, it looks insufficient. To me, it’s simply the only honest work I know how to do.

This is the safety culture argument, and it's where gun rights advocates have the strongest moral ground. The dominant paradigm sees gun ownership as inherently dangerous. The safety culture response: Anything can be dangerous if mishandled. Training reduces harm.

But I'm not naive. I know what the paradigm knows: training doesn't stop someone from shooting their spouse. It doesn't stop parking garage confrontations. It doesn't prevent pastry-related violence at the Grocery Outlet.

David Yamane argues that we need to embrace the paradoxical nature of guns: "good and bad, fun and frightening, dangerous and protective, unifying and divisive."

I teach at the range because I believe in safety culture and because I know Anna.

I worked against Measure 114 because I believe in civil rights and because I know how racist gun laws are.

I provision at Costco because I navigate ambient threat and because small ceremonies make us human-sized.

The paradigm can't hold this tension. It needs guns to be one thing: pathological, dangerous, aligned with right-wing extremism, threatening democracy.

The gun rights movement can't hold it either. It needs guns to be one thing: empowering, protective, aligned with liberty, securing freedom.

But I have to hold it. Because I'm part of the turducken.

V. Provisioning (The Return)

You pull into your driveway. The engine ticks as it cools.

The unloading starts. Rice to the pantry. Tofu to the fridge. Each jar of marinara a small prayer against the dark. You've been doing this long enough to know the prayer doesn't work. Anna still died. The Hollywood garage still happened. The Grocery Outlet is still closing. But you provision anyway, because the alternative—not provisioning, not moving, not carrying—would mean the fear wins by default. So you carry. You store. You make yourself human-sized through small ceremonies that don't prevent anything but make presence possible.

Somewhere, Daniel Snegirev sits in a cell. Eventually, jurors will be summoned. There will be voir dire. They'll sit in the courthouse I just left. They'll wait to see if their numbers are called.

Someone will be asked: "Have you been the victim of a crime?"

Someone might say: "My places of residence have been burglarized twice, and I know someone who was murdered by their spouse."

Someone will be asked: "Do you have strong opinions on guns?"

Someone might deliver their version of the constitutional turducken monologue.

And the mechanism will sort them. And twelve will be selected. And they will become, temporarily, the state.

And they will decide Daniel Snegirev's fate using whatever framework they carry into that room: the dominant paradigm, the gun rights narrative, their own lived experience, or some unstable combination of all three.

The mechanism does not require comprehension. Only participation.

The turducken metaphor isn't just about the Second Amendment's awkward syntax. It's about the entire layered, compressed, impossible-to-separate amalgamation of everything that produces the moment where I stand in a Costco parking lot, loading rice into my trunk, two miles from where someone's blood was washed away this morning.

History compressed into law. Law compressed into culture. Culture compressed into economics. Economics compressed into geography. Geography compressed into bodies. Bodies compressed into headlines.

You can't extract one bird without destroying the whole dish. You can't fix one layer without affecting all the others. You can't study just the anus and claim to understand the elephant.

The academic paradigm focuses on harm. That's necessary. Harm is real.

The gun rights movement focuses on liberty. That's necessary too. Liberty matters.

But neither can hold the full paradox: that guns are normal and people die. That civil rights require armed self-defense and armed self-defense kills. That safety culture reduces accidents and accidents aren't the problem. That 20-30 million AR-15s exist and we can't unscramble that egg.

The turducken is already cooked, and we've been eating it. The only question is whether we can taste all the layers, or whether we'll keep insisting it's just chicken, just duck, just turkey.

I teach people not to be Alec Baldwin.

Daniel Snegirev allegedly shot two people in a parking garage.

Anna was shot twice in the head by her husband.

The Grocery Outlet is considering closure.

The MAX train station has a memorial.

I load rice into my trunk and drive home.

All of this is true. All of this is the turducken. None of it resolves.

You were there. You're still there. That changes everything. And nothing.

This is why we can't have nice things.