Why Academic Journal Editors Can’t Be Gerard Cosloy

Every academic reviewer knows the moment. You open a paper, read the abstract, skim a page or two, and your body registers the truth before your brain formalizes it: this is competent, coherent, and not worth your time. Nothing is wrong. The thesis isn’t false. The citations check out. The prose moves correctly from premise to conclusion. And yet—cold oatmeal. Nutritionally adequate, spiritually dead.

You know this within minutes. But the system does not permit you to act on that knowledge.

Instead, you read the whole thing. You annotate. You draft careful comments. You justify your eventual rejection in procedural language that disguises the actual reason: this paper does not matter. The labor can take hours. Multiply that by dozens of submissions, and exhaustion becomes a professional obligation.

This is not a failure of standards, intelligence, or goodwill. It is a failure of role design.

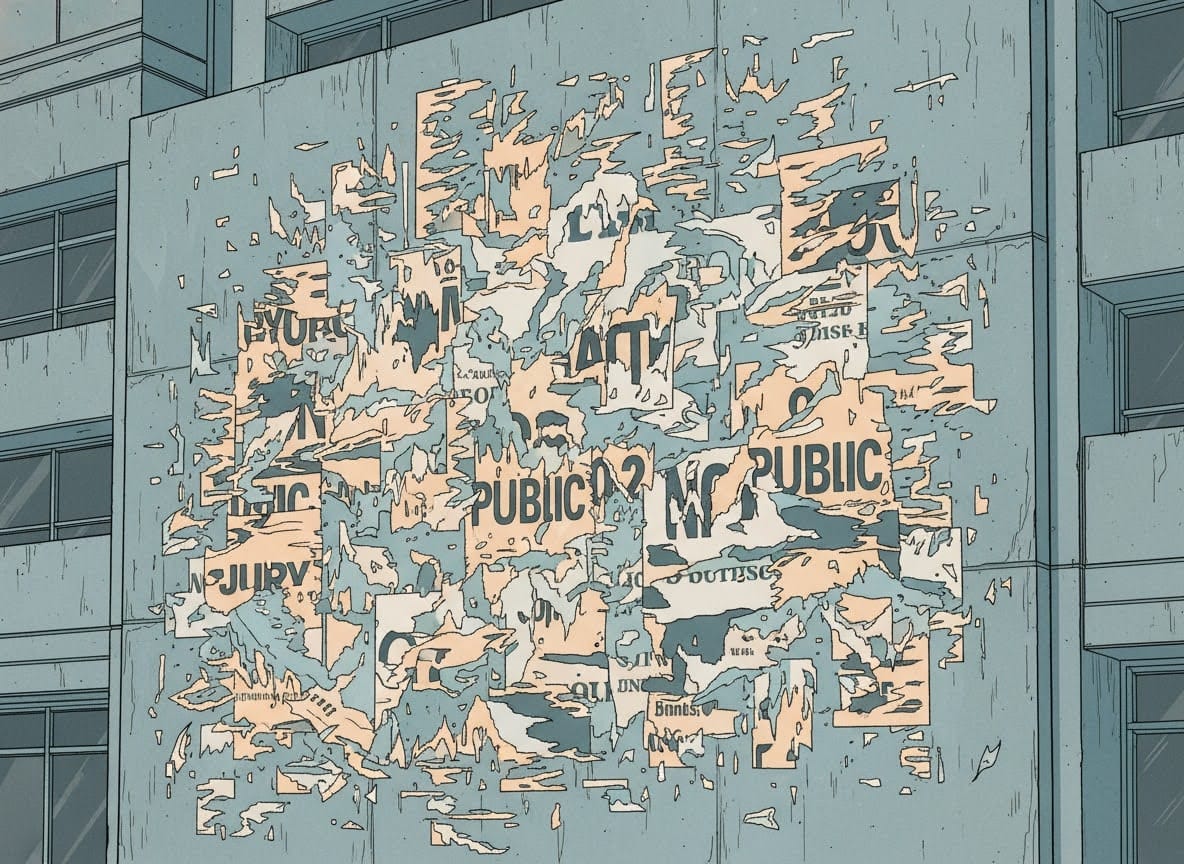

Academic journals are now facing what music labels, publishers, and cultural institutions confronted decades ago: abundance. Too many submissions, too little attention, and dramatically lowered costs of production. Generative AI didn’t create this problem, but it removed the last friction that made it tolerable. What AI has exposed is not a collapse of rigor, but a contradiction at the heart of academic evaluation—editors are curating while being required to pretend they are not.

To see the contradiction clearly, it helps to ask a question academia refuses to articulate:

Whom would Gerard Cosloy sign?

Cosloy—co-founder of Homestead and Matador Records—was not trying to determine which bands were objectively “good.” He was curating a catalog. His decisions were fast, subjective, and unapologetically taste-driven. A band didn’t need universal appeal; it needed to belong there. If it didn’t, it was rejected quickly, without moral theater. If it did, Cosloy bet real resources—studio time, promotion, reputation—on that judgment.

This contrast matters because Cosloy’s authority was explicit, bounded, and accountable. He was not pretending to represent music in general. He was curating a sensibility within a plural ecosystem of labels. False negatives were inevitable and acceptable because there were other doors. His power was checked not by procedure but by consequence: if his taste stopped mattering, the label suffered.

Academic journal editors operate under almost the opposite conditions.

They are expected to act as neutral stewards of a universal enterprise called “scholarship.” Their authority is diffuse, procedural, and defensive. Decisions must be justified in ways that can survive grievance processes, appeals, audits, and reputational scrutiny. Speed looks like carelessness. Conviction looks like bias. Saying “this is not what we do” sounds exclusionary, even when it is obviously true.

And yet editors are still choosing. They choose what topics fit, what methods count, what conversations matter, what risks are acceptable. They just aren’t allowed to say they’re choosing. So judgment is laundered through process. Taste is disguised as rigor. Curation becomes invisible and unaccountable.

This arrangement worked—barely—when submissions were scarce and costly. It collapses under abundance.

AI-generated text doesn’t overwhelm journals because it is obviously fraudulent. It overwhelms them because it industrializes plausibility. It produces work that mimics the surface features of acceptability—coherence, citation density, methodological orthodoxy—while bypassing the human commitments that once limited volume. The result is not an influx of nonsense, but an explosion of work that sits just above the floor of “good enough.”

The damage is not that bad work gets published; it’s that mediocre work consumes the attention that would otherwise go to risky, surprising, or field-shifting ideas.

The system responds by doubling down on procedure. More reviewers. Longer reports. More elaborate justifications. The cold oatmeal must be chewed to completion, because rejecting it quickly would require admitting the real criterion: interest.

That admission is taboo.

Academic fairness norms evolved to prevent real harms—capricious gatekeeping, old-boy networks, ideological exclusion. Blind review, written justifications, and collective decision-making were not bureaucratic accidents; they were hard-won reforms. But they were designed for a world of scarcity, where evaluation labor was finite but manageable, and where the primary risk was false negatives.

We now live in a world where the primary risk is false positives at scale, and the safeguards designed to prevent injustice are being used to protect volume and mediocrity.

The tragedy is that academia did not eliminate gatekeeping. It made it worse.

Gatekeeping still happens—by prestige, institutional affiliation, topic fashion, stylistic conformity—but now it is slow, opaque, and plausibly deniable. Everyone pays the cost, and no one is accountable for the outcome. Editors burn out. Reviewers disengage. Authors shotgun submissions everywhere because routing signals are nonexistent. The system rewards appearing busy over being right or interesting.

Cosloy’s world functioned because selection was front-loaded. Routing preceded evaluation. Misfit was cheap to reject; commitment was expensive to offer. Academia reversed that logic. It exhausts itself evaluating misfit work and offers minimal commitment to what it accepts—often a PDF quietly added to a database.

This is why calls to “detect AI slop” miss the point. Even a perfect detector would not solve the problem. A human can produce cold oatmeal just as effectively as a machine. The crisis is not authorship; it is legitimacy. The signals we use to recognize work that matters are being drowned by work that merely passes.

The obvious response—“editors should be more decisive”—fails because it ignores the ecosystem. Cosloy could be Cosloy because rejection was not exile. There were other labels, other scenes, other paths. In academia, where careers hinge on a handful of prestige markers, a fast no can be catastrophic. That is not an argument against curation; it is an argument for pluralism.

Real reform would require conditions academia has systematically denied:

Clear editorial identities—journals that state explicitly what kind of work they publish, and fast-reject mismatches without apology.

Multiple viable venues so rejection routes rather than erases.

Reduced career stakes per publication decision.

Editors whose judgment is visible and therefore accountable.

None of this can happen while journals pretend they are not curating.

Here is the contradiction academia cannot escape: academic editors cannot be Gerard Cosloy because the role forbids admitting that signing is what they are doing.

Until that pretense is abandoned, the system will continue to confuse process with quality, exhaustion with virtue, and fairness with universal consumption. AI did not break scholarly publishing. It removed the last illusion that allowed a structurally incoherent role to function.

The question is no longer whether editors should act like curators. They already do. The question is whether academia is willing to build an ecosystem where curatorial judgment is legitimate, plural, and survivable—or whether it will continue drowning in cold oatmeal it insists everyone must finish.