Unmarketable by Design

Accounting for a Disappearing Network

Movietone, Crescent, and the wider Bristol post-rock network were not simply “good bands from a cool scene.” They were proof that, briefly — very briefly — a particular alignment of economic, social, and infrastructural conditions made it possible for unmarketable music to exist without having to justify itself commercially.

That alignment is gone. What remains is not a mystery, a tragedy, or a failure of taste. It’s a ledger problem.

This isn’t nostalgia. It’s accounting.

What Existed

The music that came out of Bristol in the late 1990s and early 2000s — the patient drift of Movietone, the band-as-body looseness of Crescent, the adjacent orbits of Flying Saucer Attack, Pram, and others — depended on a set of material conditions that were not accidental, even if they were rarely named.

Rent was cheap enough that people could rehearse without monetizing rehearsal. Record shops functioned as browsing spaces, not just retail endpoints. Labels existed that could tolerate slow returns and modest sales. Attention moved at human speed, not algorithmic speed. Slowness, imprecision, and collective feel were culturally permitted rather than framed as errors to be corrected.

None of this made the music inevitable. It made it possible.

This is the key distinction that gets lost when we talk about “scenes.” Scenes sound organic and self-generating. Networks tell a truer story. What existed in Bristol was a network of tolerances: economic tolerance for low yield, cultural tolerance for ambiguity, social tolerance for work that didn’t announce its own value.

Movietone could record an album intending it to sound “like a jazz record being played from across the bay” because no one required that intention to translate into a hook. Crescent could make a record where the singer evaded every available vocal trope — not wounded, not ironic, not charismatic, not heroic — because nobody demanded legibility as the price of existence. Bands could function as bodies rather than hierarchies, negotiating time internally instead of submitting to an external grid.

The music didn’t need to persuade. It didn’t need to optimize. It didn’t need to perform importance.

What It Cost — and Who Paid

Those conditions were not free. They were subsidized.

Cheap rent subsidized failure and rehearsal.

Record shops subsidized discovery and slowness.

Labels subsidized patience by absorbing risk.

Pre-algorithm attention subsidized work that required time to reveal itself.

Cultural permission subsidized imperfection and looseness.

The cost of these subsidies was distributed — landlords accepting lower rents, shops carrying inventory that moved slowly, labels taking smaller margins, listeners spending time rather than clicks. None of this was heroic. It was simply how the system functioned.

Crucially, the artists themselves were not the only ones paying. The network worked because the burden was shared.

That’s what “community” meant in practice: not vibes, not identity, but shared tolerance for non-optimized outcomes.

What Killed It

The disappearance of this network didn’t require villains. It required incentives.

Rents rose.

Retail consolidated, then collapsed.

Labels professionalized and narrowed their risk tolerance.

Attention became quantified, sorted, optimized, and fed back into production.

Imperfection stopped reading as human and started reading as unfinished.

Nothing dramatic had to happen. No one needed to ban this kind of music. It simply became unviable to support at scale.

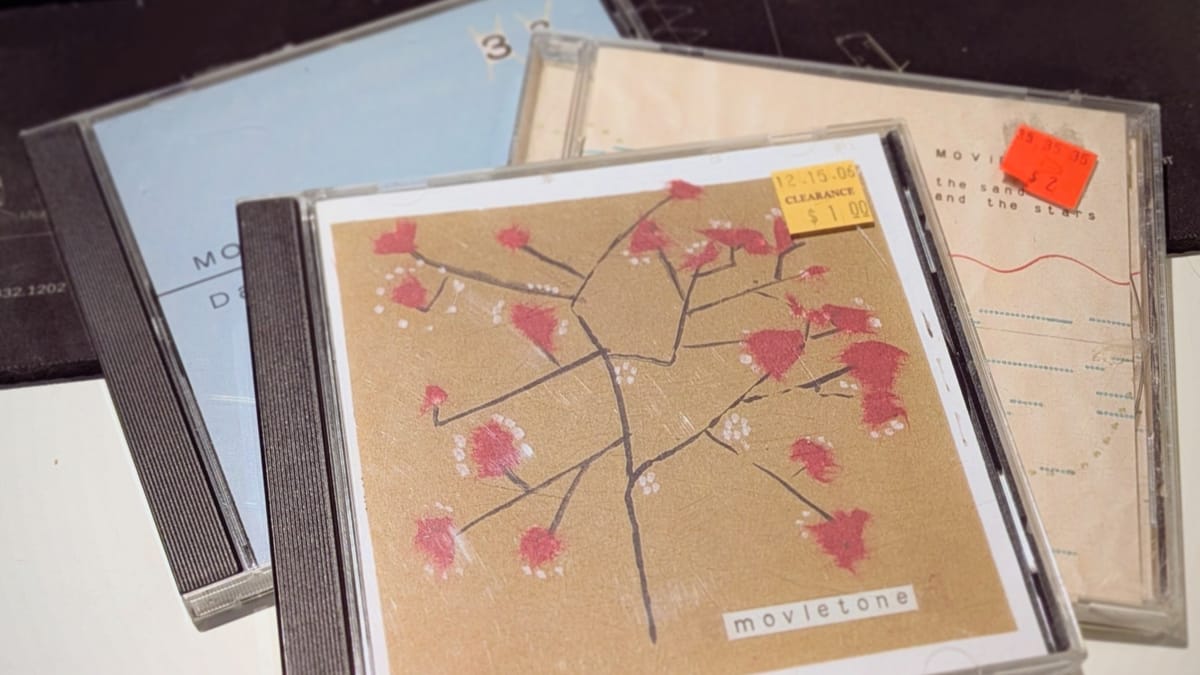

When Domino won’t license later Movietone albums for reissue, that’s not malice. It’s arithmetic. When CDs end up in $1–$2 clearance bins and then quietly vanish, that’s not rejection. It’s inventory logic. When the only remaining access points are Discogs listings, mp3 blogs, YouTube uploads, and word-of-mouth recommendations, that’s not underground romance. It’s what’s left when formal infrastructure withdraws.

The system didn’t decide this music was bad. It decided it wasn’t worth maintaining.

What Persists — and How

What survives now does so through informal custodianship.

People with enough space to store records and hard drives.

People with enough time to dig through clearance bins and second-hand shops.

People with enough cultural literacy to recognize value where the market doesn’t.

People with radio shows, blogs, or social circles that still operate outside algorithmic sorting.

This custodianship is unpaid, unevenly distributed, and dependent on privilege. That’s the uncomfortable part most revival narratives avoid. Keeping this music alive now requires surplus — of time, money, stability, and attention. It’s not democratic. It’s not scalable. It’s fragile.

And yet it persists.

Movietone CDs bought for a dollar, played years later with full attention.

Crescent records rediscovered not as artifacts, but as evidence of another way of sounding together.

Networks maintained through conversations at places like Café OTO, Sacred Harp singings, radio studios, and kitchen tables.

This isn’t a comeback. It’s maintenance.

What We’re Actually Mourning

When people say they want “community back,” they’re rarely asking for another band or another record. They’re mourning the disappearance of shared subsidies that made unmarketable work viable without turning it into a lifestyle brand or a side hustle.

They’re mourning the loss of time that wasn’t measured.

Of attention that wasn’t ranked.

Of music that didn’t have to justify its existence.

Of collective looseness in a world that now demands correction.

Movietone and Crescent don’t point backward as lost ideals. They point sideways, as documentation. They show what happens when bodies are allowed to play together without being hurried, optimized, or made legible for sale.

Nothing here needs rescuing. The music is still there. The records still play. The questions remain open.

But the conditions that made this kind of work ordinary rather than exceptional are gone. Naming that isn’t nostalgia. It’s accounting.

And accounting is the first step toward understanding what it would actually take — materially, not romantically — for something like this to exist again.