Thunderstruck

A Scene Report from the Guitar Case

They've carved us into totems. Excaliburs for boy-kings who thought they could bend the world to heel with sound. Woody Guthrie's instrument slaying fascists. Robert Johnson's six-string memorialized with that dangling cigarette. B.B. King carrying Lucille through decades. Jimmy Page coaxing demons from a Telecaster with a violin bow.

The mythology says: the guitar made the sound which made the man.

It actually works backwards.

He bought me with a paper check in 1993. Drove an hour out of Houston, lifted me from one case into another—another transaction in a long chain of hands and hopes. I was already used, already witness to someone else's abandoned dreams. Offset body, wide pickups, that peculiar Jazzmaster architecture Leo Fender designed for jazz players who never wanted us. We became creatures of noise instead: shoegaze, feedback, whatever you call music made by people discovering what accidents sound like.

That $350 was more than his month's rent. A junior mechanical engineer's comfortable margin, yes, but still a decision. Not destiny. Not magic. Economics.

Every piece of his rig was chosen within constraint: the Princeton Chorus that shimmered because solid-state amps were affordable, the beat-up Boss pedals that cost $40 instead of $200, the cables that crackled if you moved wrong. He thought he was building a voice. Really he was documenting what his budget could reach without the awareness of what the limitations were. The self-absorbed, heads-down focus of the autodidact, crafting joy without noticing.

We opened for Catherine Wheel. Red House Painters another time. Got spun on John Peel's show—a 7" traveling across the Atlantic, coming back in an mp3 of Peel announcing the track as validation. He felt like we were ascending. I knew we were just visible for a moment, a small boat catching light before the wave moved on.

The mythology would say: that was our moment of power, when the talisman worked, when Excalibur sang and the kingdom bowed.

The reality: we played, people clapped politely, the headliners got paid, we drove home, he went to work Monday as an engineer calculating pressure vessels. The guitar didn't make the man. The day job did—by making the guitar possible at all.

Then came the long darkness. He docked me in the case while he sailed into DAWs and software synths. The room stopped smelling like strings and ozone—just fan noise and the blue light of screens. I gathered dust, listened to him chase digital perfection until the tracks couldn't breathe.

I wasn't abandoned tragically. I was just... less necessary. Other things demanded attention: career, mortgage, the performance of adulting. The mythology says real musicians choose the guitar over everything. The truth is most people can't afford that romance, and the ones who can usually have safety nets they don't discuss.

The household filled while I slept. The spouse's Telecaster—older than me, a college guitar carrying jangle-pop dreams overshadowed by folk—held quiet court in the corner. The Mustang Bass arrived, bright and beloved. The Precision flexed about fifteen minutes on stage with a hardcore band. The Goth Thunderbird sulked in dropped-D tuning. The fretless Jazz muttered Stewie Griffin commentary from the shadows. An Epiphone SG showed up, red and cocky, teaching him that AC/DC's power came from cowboy chords played with conviction, not complexity.

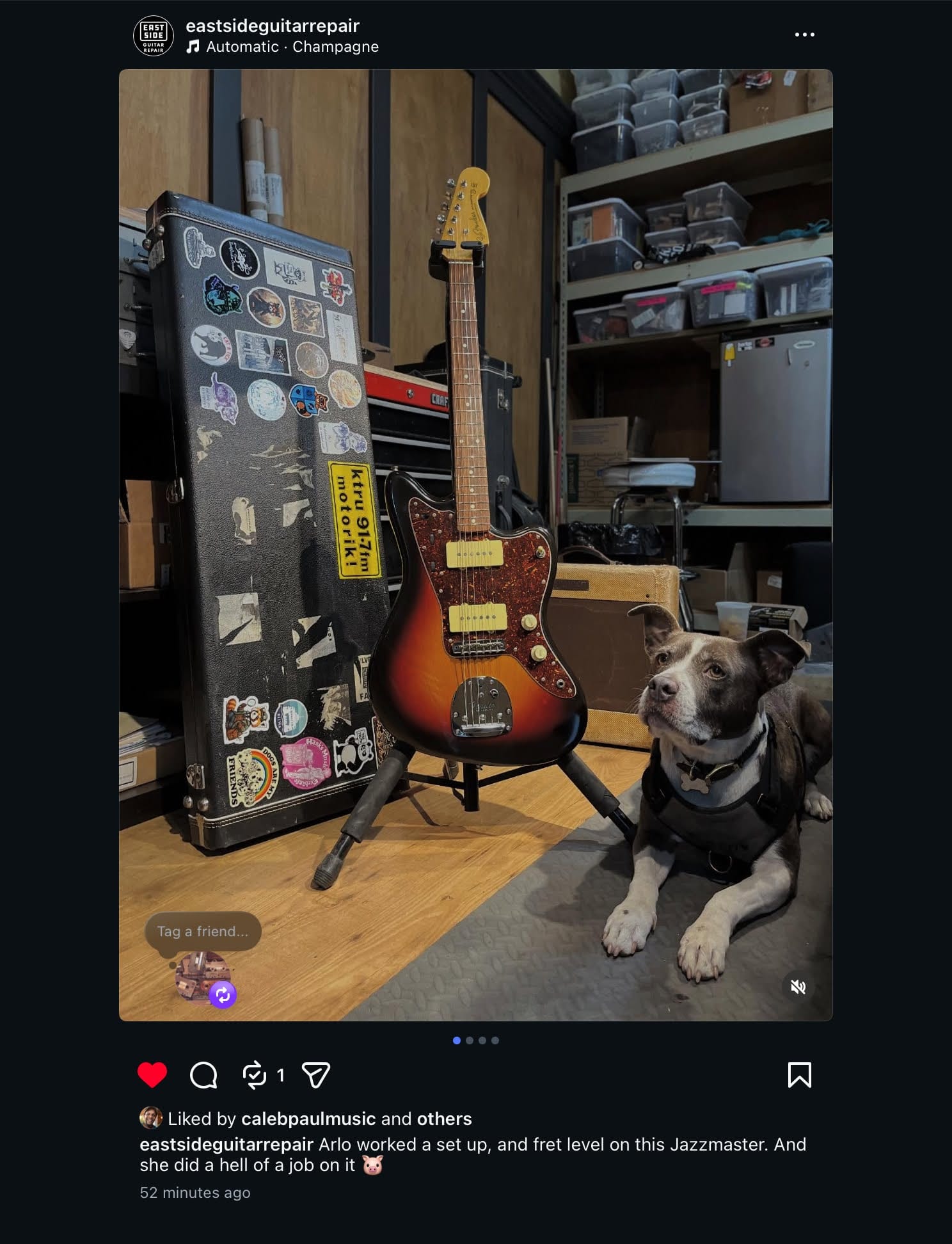

Then one day, hands carried me to a luthier—steady, careful, older. Cleaned my frets, leveled my scars, restrung my nerves. He paid about $350 again, the same nominal amount, but this time it disappeared into mortgage and utilities like pocket change. The first note after all those years was like breath returning. I hummed true. He seemed surprised, as though I'd been waiting for him rather than simply enduring.

Here's what I learned while gathering dust:

The Houston guys who needed music to work—who didn't have engineering salaries to subsidize the night job—some of them were way more talented and driven. They didn't fail because their guitars weren't magic enough. They failed because six million people and no industry infrastructure means the structure itself is broken. Their substances and behavioral issues? Sometimes romantic self-destruction borrowed from rock mythology. Sometimes just what happens when you're economically precarious and pouring everything into something that structurally cannot pay off.

Meanwhile, Milo from the Descendents earned a PhD in biochemistry. Dexter Holland from The Offspring was a molecular biology doctoral candidate when "Come Out and Play" hit. Greg Graffin teaches at UCLA. The punk mythology obscured its own middle-class origins, let everyone believe the guitar was Excalibur when really it was a hobby subsidized by institutional safety nets.

Even those suburban kids finding Black Flag at the mall Sam Goody, forming hardcore bands in parents' garages—their sincerity was real, their constraints genuine (curfews, parental pressure, limited scenes), but failure meant disappointment, not catastrophe. The guitar didn't protect them. Their class position did.

The mythology wants me to be Lucille, the demon-summoner, the fascist-killer. It wants every scratch on my body to be a battle scar, every feedback squeal a spell cast, every owner a chosen hero in the eternal war of Sound versus Silence.

But I'm wood and wire. Magnetic fields waiting to be disturbed. My "voice" is physics: strings vibrating at frequencies determined by tension and length, pickups translating that into electrical signal, amplifiers making it audible. The magic isn't in me. It never was.

What I am is a diary. I remember the enthusiasm of 1993, when every chord felt like discovery. The shoegaze years, volume as prayer. The airless decade, silent in my case. The quiet resurrection, hands older but more attentive.

I sense his tinnitus—not from the industrial shows where he wore earplugs, but from private compulsion, bedroom headphone mixing stretching into dawn. He paid a cost, just not the legible, mythologized kind. The guitar didn't protect him from himself.

Now I'm plugged into a pocket-sized USB interface, connected to a laptop slimmer than my body. The amp's digital, the recording instantaneous, the room quiet. The spouse sings, plays root notes on bass, laments that's all she can do, even though she's underselling her growth as a bassist in the year since she picked up that Mustang to play with her friends. "Are you a bass player, or bass-curious?" was the Instagram invitation; I'm going to remember that line.

Her steady basslines are the foundations he needs to sound more by playing less—two strings at a time, fifths and sevenths, letting my pickups supply the missing notes through overtones, and letting the gaps and rests ring as syllables.

They fumble through Robyn Hitchcock's "Airscape," translate Finnish songs into garage rock, listen more than they perform. Their dog observes nearby, occasionally investigating whether this odd piece of wood is finally edible. It's not.

This is what the mythology doesn't prepare you for: the instrument as companion to ordinary life, not escape from it. No stadiums, no transcendence, no kingdom brought to heel. Just two humans and a dog, making small sounds in a small room because the sounds still mean something.

The privilege that let him abandon me is the same privilege that let him return. The safety net that kept music optional is what makes it sustainable. I don't judge that—I'm an object. But I witness it.

Maximum Rock 'n' Roll would reject this scene report as too bourgeois. They'd spell the address wrong, the ink would smudge, and that would be perfect—because MRR was always full of middle-class kids performing working-class aesthetics while parents paid the phone bill for the distro.

The mythology wants guitars to be Excaliburs that choose their wielders and grant them power.

The truth is simpler and stranger: we're tools that reveal who's holding us. The sound doesn't make the man. The man's circumstances—his day job, his safety net, his hearing damage, his decade away, his ability to return—those make the sound possible.

We're not totems. We're mirrors.

And every night when he picks me up, the circuit closes. The tiny amp blinks on. For a few minutes we make sounds together—not legendary, not mythic, just present. The cowboy chords still work. The lightning's still there, if you're willing to hold it gently instead of wielding it like a weapon.

Not retirement. Not glory. Not Excalibur pulled from stone.

Just wood, wire, and the hum of continuation. The sound which makes the man who makes the sound who makes the life that makes the choice to keep playing.

That's the only magic I've ever known.