The Snakes and the Basket

Under the Hood of Dalis Car

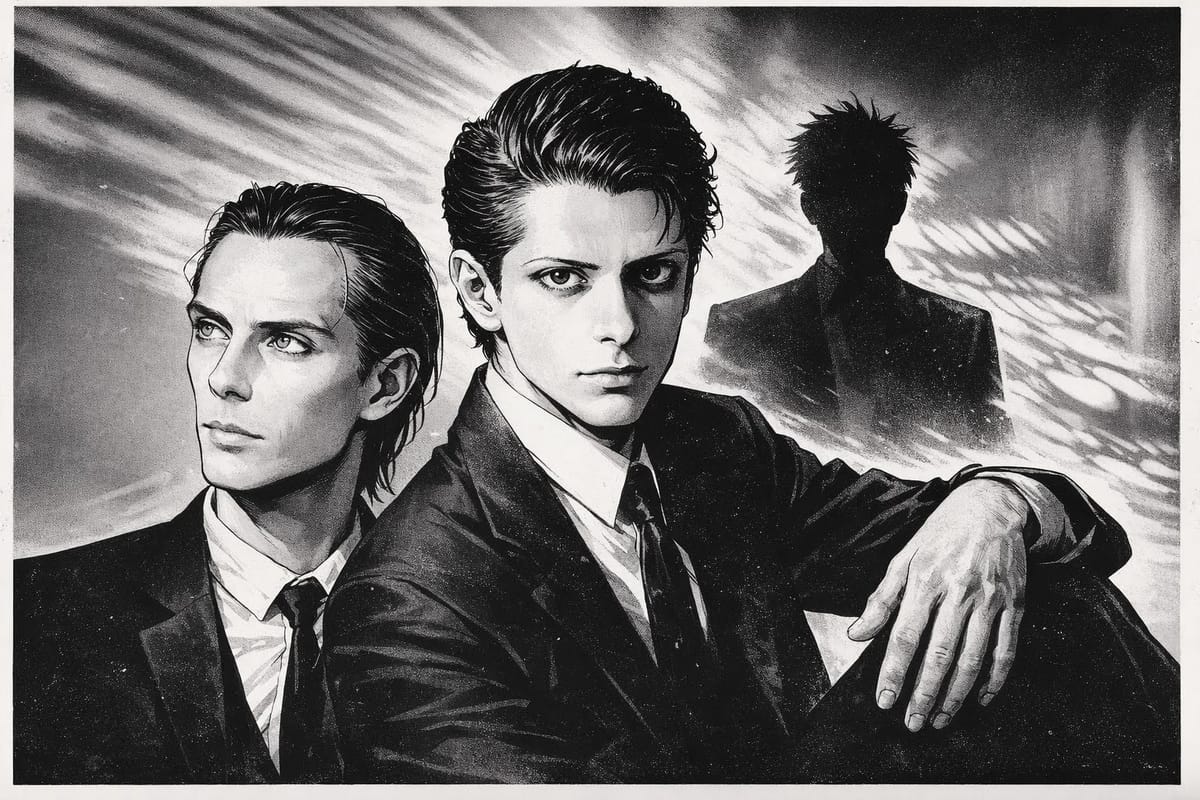

Dalis Car looked inevitable on paper. Peter Murphy, newly untethered from Bauhaus, carrying theatrical gravitas and mythic self-regard. Mick Karn, freshly freed from Japan, bringing one of the most elastic and idiosyncratic instrumental voices of his era. The promise was obvious: nocturnal art rock with pedigree, danger, and intelligence to spare.

What emerged instead, on The Waking Hour, has long been treated as a misfire. Reviews then and now tend to orbit the same complaints: stiffness, over-programming, a lack of “band feel.” The mechanical rhythms are often cited as the album’s fatal flaw. But that reading misses what the record is actually doing. The problem isn’t that Dalis Car failed to sound human. It’s that it solved a human problem using structure rather than expression.

At the center of the misunderstanding are the programmed beats.

Listeners often expect rhythm to emote—to breathe, to swing, to argue back. But on The Waking Hour, the beats are not expressive. They are structural. They establish a non-negotiable floor. Time does not bend. Pulse does not flatter. Everything else must decide how to exist within that constraint.

This isn’t coldness. It’s containment.

Murphy and Karn are not artists who benefit from looseness by default. Both are prone to coiling elaboration. Murphy declaims, inhabits, overwhelms. Karn bends pitch and harmony until gravity itself feels optional. Left unmoored, that energy doesn’t become freer—it becomes unstable. The music risks collapsing under the weight of its own intensity.

The machine pulse is the basket holding the snakes.

Crucially, that pulse was programmed by Paul Vincent Lawford—the youngest, least mythologized participant in the project, and the one most often written out of its history. Lawford’s role is rarely foregrounded in retrospectives or even publicity photos, yet his contribution may be the most consequential. The “adult in the room” many listeners intuitively hear was not imposed by a producer or auteur, but built from below by someone who understood that the collaboration could only survive if time itself refused to negotiate.

Seen this way, the drum programming stops being a stylistic compromise and becomes a survival strategy.

This reframes the album’s critical reception as a case of misrecognition. Reviewers often judge The Waking Hour by the standards of bands: chemistry, swing, collective breath. But Dalis Car is not a band document. It is a negotiated settlement. What sounds rigid is actually protective. What seems withheld is precisely what allows the volatile elements to coexist without destroying each other.

That logic mirrors a parallel conversation in mastering practice.

There are two competing visions of what a master should do. One is interventionist: tidy the spectrum, manage dynamics aggressively, anticipate hostile playback conditions, and solve problems preemptively. The other proposes rather than dictates. It leaves room for variability, trusts listeners to engage with their equipment, and optimizes for robustness rather than uniform translation.

This isn’t merely technical preference. It’s a question of relationship.

The interventionist approach centralizes authority in the file itself. It assumes inattentive listeners and worst-case systems. The open approach distributes authority downstream. It assumes collaboration—that listeners will turn knobs, move speakers, adjust rooms, and complete the work in context. One closes possibilities in the name of control. The other multiplies them through trust.

Here’s where the lines converge.

Lawford’s programming functions exactly like an open mastering philosophy. The beats do not attempt to anticipate every expressive need. They establish a framework and refuse to overcorrect. They create conditions where dangerous elements can remain themselves without canceling each other out. Constraint here is not coercion; it is care.

This is structure as mutual aid rather than dominance. Anarchist in the proper sense: no single authority determining outcomes, but shared frameworks that allow multiple agencies to coexist.

The irony is that both approaches—open mastering and The Waking Hour—are often accused of the same crime: being cold or lifeless. But coldness and constraint are not the same thing. One shuts down possibility out of anxiety. The other creates space for it through discipline.

Time has been the best judge. As musical culture has grown more literate about machine pulse and dynamic range as aesthetic choices rather than technical failures, The Waking Hour reveals itself more clearly. What once sounded stiff now sounds deliberate. What seemed incomplete becomes generative.

The album’s final, bittersweet coda—Murphy and Karn reconnecting decades later, only months before Karn’s death—underscores this. Dalis Car was never resolved. It was held in suspension. The record survives because its tensions were never eliminated, only contained.

Under the hood, The Waking Hour is not a story about technology replacing humanity. It’s about structure stepping in where human systems failed. A nervous newcomer building an immovable floor so brilliance didn’t tear itself apart.

No gods, no masters, and no deluxe remasters—only listeners. And only structures generous enough to let something dangerous and beautiful exist at all.