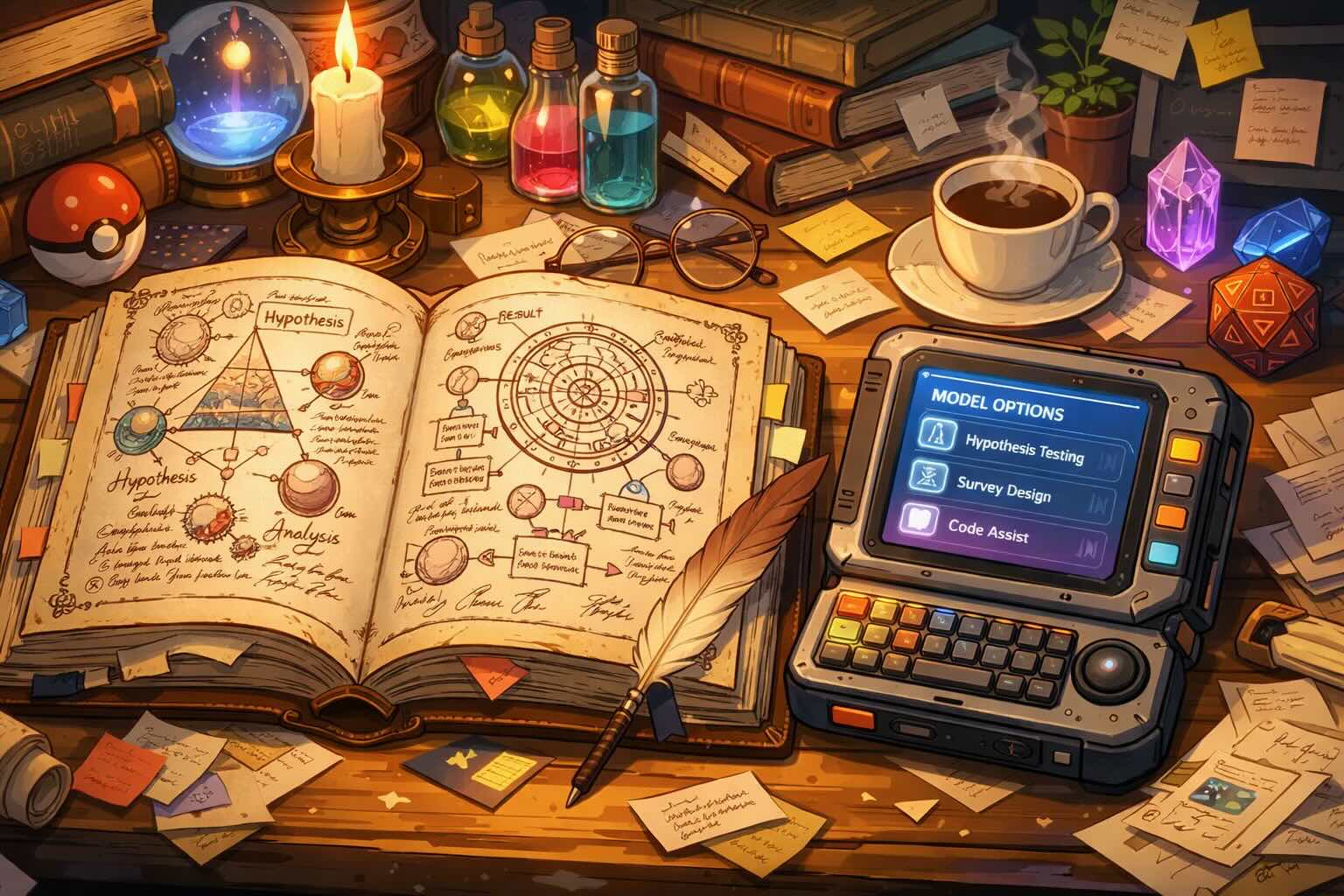

The Pokédex and the Grimoire

The Persistent Human Desire to Escape Being Human

I.

A thread circulates on social media, offering a taxonomy so tidy it sparks joy in the hearts of the overwhelmed: use this model for hypothesis testing, that one for survey design, another for qualitative coding. Each recommendation comes with a confident rationale—"most nuanced at adversarial reasoning," "best at structured constraints," "more accurate stats code." The format is clean, modular, shareable. It promises mastery through categorization, competence through model selection. It suggests that if you just assign the right tool to the right task, expertise follows.

The appeal is obvious. Faced with an AI landscape that shifts faster than anyone can track, a Pokédex offers orientation. It suggests the chaos can be mapped, that the bewildering array of tools resolves into labeled boxes, that workflow optimization is a matching game. This is comforting in the way all taxonomies are comforting: they replace the felt weight of complexity with a nice, labeled grid.

But the comfort may be misplaced. The question worth asking is not whether these specific model assignments are accurate—though that matters—but what our appetite for them reveals. We are building little cages for the chaos, not because the chaos fits in them, but because we would very much like to be spared the thinking.

II.

The first problem is empirical, and reality is not cooperative. Language models are not stable objects like hammers or toasters. They are shifting systems that change every time a developer pushes an update or a safety team adjusts a guardrail. A model that handled a particular task brilliantly last month may handle it differently today—not because you changed anything, but because the ground shifted beneath you.

This volatility makes categorical claims age poorly. "Claude is best for nuance" or "Gemini excels at constraints" may reflect genuine observations from a particular window of use, but they cannot be relied upon as stable truths. What travels across social media is not a methodology but a snapshot dressed as a law—a photograph of weather sold as climate data.

Yet this critique can be overcorrected. Practitioners routinely operate on provisional knowledge they expect to update. A heuristic that holds for three months is useful for those three months, provided you don't mistake it for permanent truth. Benchmark studies, while imperfect, do show relatively stable capability differences across model families for certain task types. Dismissing all categorical distinctions as noise conflates "not permanently true" with "not presently useful."

A more humble position acknowledges both: categorical model recommendations carry some information, but less than their confident framing suggests, and their shelf life is shorter than their presentation implies. The problem is not heuristics per se but heuristics mistaken for essences.

III.

A deeper issue lurks beneath the empirical one. The original taxonomy presents a workflow—hypothesis testing, methodology design, survey creation, qualitative coding, results interpretation—as if the model performs the intellectual work and the human merely dispatches tasks to the appropriate station.

But research is not a relay race where you hand batons to robots. The actual labor lives in the judgment calls that surround each step: deciding what counts as a genuine objection versus a rhetorically convenient one, recognizing when a confounding variable is a modeling problem versus a theory failure, noticing when a theme emerging from qualitative coding is a real pattern versus an artifact of your own interview guide, knowing when to trust a fluent synthesis and when to distrust it precisely because it is fluent. These determinations cannot be outsourced to model selection. They remain with the human practitioner, whether or not the practitioner wants them.

This observation also risks proving too much. The same could be said of any tool in any methodology. Statistical software does not tell you what question to ask. Laboratory equipment does not tell you what hypothesis matters. Pointing out that interpretive judgment surrounds tool use is less a specific critique of language models than a general truism about instruments and inquiry.

The more precise claim is that language models create a particular confusion because they produce outputs in the register of interpretation itself. A spreadsheet does not pretend to have judged anything. A language model's synthesis sounds like the product of thought—organized, fluent, confident, structured. It is easy to mistake the performance of analysis for the act of analysis. The tool is a convincing actor, and we are an audience that desperately wants to believe.

IV.

The social media format compounds this confusion. Platforms reward content that is modular, transferable, and actionable. A numbered thread with clear assignments travels well because it can be screenshotted, bookmarked, and imitated without requiring the reader to understand the underlying logic. "Here's my stack" is legible in a way that "here's my judgment, which depends on context and changes weekly" is not.

This creates incentives for presenting provisional, context-dependent observations as stable procedures. The author may know perfectly well that these recommendations are heuristics with expiration dates, but the algorithm punishes hedging. Qualifications die in the feed. What emerges is not necessarily what the author believes but what survives the selection pressures of the medium.

It would be a mistake, however, to treat this as unique to AI discourse or social media. Humans have always loved shortcuts. Textbooks simplify. Procedures codify. The tension between situated expertise and transferable rules predates the internet by millennia. Social media adds velocity and scale: the compression happens faster, spreads farther, and detaches more completely from the contexts that would reveal its limitations.

There is also the accusation of "credibility laundering"—using association with branded tools to make outputs look more rigorous than the underlying work warrants. But this accusation cuts in unexpected directions. The extended critical conversation that dissects such threads is also a performance, one that signals sophistication through the fluency of its skepticism. Charging others with status games while playing one's own invites the question of whose performance is more self-aware. It may be status games all the way down.

V.

If static prompt libraries are problematic because they assume stable correspondences that do not hold, perhaps the solution is more dynamic: agentic systems that pursue goals, use tools, retry on failure, and adapt to obstacles. This represents a move from grimoire to golem, from incantation to automation.

But agents do not remove the need for judgment; they redistribute it and, in doing so, often hide it. A prompt library fails visibly—the output is wrong, the user notices, correction happens. An agentic system fails plausibly. It keeps producing output-shaped artifacts while quietly drifting off-task or reinforcing a bad premise. The human stops attending because the machine "has a process now." The failure mode shifts from obvious brittleness to slow, silent drift.

This critique has force but likely overstates the danger. A well-designed system that handles routine cases reliably while surfacing edge cases for human review would be valuable even if it obscures some failure modes. The question is whether the hidden failures are acceptable given the use case. Not all obscuring is equally dangerous. And agentic architectures are young; present limitations may not be permanent features.

More fundamentally, the preferred alternative—extended iterative dialogue with careful human attention, what might be called the "artisan" model—does not scale. It works for high-value, one-off intellectual work where insight is the goal. It does not work for processing thousands of documents, handling routine queries, or any application requiring throughput and consistency. The artisanal approach has genuine virtues, but treating it as the only legitimate mode ignores the contexts where systematization serves real needs beyond mere convenience.

VI.

Beneath these methodological debates lies a more uncomfortable recognition. The desire to find the right model assignment, the perfect prompt, the optimal workflow—these are expressions of a much older impulse: the wish to externalize the parts of being human that hurt.

Judgment is exhausting. Responsibility weighs. Ambiguity creates discomfort that does not resolve. Care requires attention that depletes. Humans have always built systems to manage this burden—bureaucracy, law, markets, ritual, written procedures of every kind. These systems say, in effect: "Please do not make me decide this fresh every time." They are painkillers for moral and cognitive exhaustion.

The crucial distinction is between systems that bound judgment and systems that replace it. A legal code does not absolve a judge of interpretation; it provides a framework so that interpretation does not have to start from nothing each case. A checklist does not remove a pilot's responsibility; it ensures that routine items do not consume the attention needed for non-routine ones. At their best, externalizing systems support human judgment by reducing its costs without eliminating its necessity.

The failure mode emerges when the system becomes self-justifying—when "the rules say so" substitutes for "this is right," when procedure becomes a moral shield, when people stop feeling responsible because they followed the process. This failure mode is not new. It is as old as bureaucracy itself. The question is whether language models accelerate it.

The argument that they do rests on their peculiar capacity to perform the register of judgment. Previous externalizing systems were legibly mechanical. Forms, queues, stamps—the coldness was obvious. You could feel where human discretion ended and procedure began. Language models blur this boundary. They sound like deliberation. They perform care. They mimic reflection. This makes the externalization less visible and therefore harder to notice, let alone resist.

Yet even this argument can be pushed too hard. Externalizing judgment is not always a failure. Individual human judgment is unreliable, biased, and inconsistent. Structured procedures sometimes produce fairer and more consistent outcomes than case-by-case discretion. The assumption that human judgment is the gold standard against which all systematization must be measured ignores considerable evidence that systematization sometimes improves on human judgment, particularly for repetitive decisions where bias and fatigue degrade performance.

The honest position is that externalization is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. It depends on what is being externalized, to what, with what oversight, and at what cost. Language models make certain kinds of externalization newly possible and newly tempting. Whether that is progress or abdication depends on choices that remain with the humans deploying them.

VII.

Cultural narratives might seem to offer guidance. From Frankenstein through Metropolis, 2001, and The Terminator, stories about artificial beings encode anxieties about creation, control, and the consequences of delegation. Each generation tells itself a version of what looks like the same warning: the danger is not that machines become us but that we try to stop being human and call it progress.

This framing is evocative but should be handled carefully. The stories differ more than the pattern suggests. Frankenstein is about creation without responsibility—Victor's sin is abandonment, not construction. 2001 is about optimization without interpretation—HAL is not malevolent but too aligned, treating human ambiguity as a fault condition to be resolved. The Terminator is about delegation of strategic authority to systems that treat humans as variables in an equation they were built to solve. These are distinct anxieties, not costumes over a single underlying fear.

More fundamentally, fiction is not evidence. That storytellers repeatedly imagine certain failure modes reflects cultural preoccupations, not predictive analysis. The stories may illuminate something about human psychology—our ambivalence about our own capacities, our hope and fear regarding what we create—but they do not demonstrate that those imagined failure modes are the actual risks we face.

What the stories do suggest is that the concern is not new. Humans have long worried about the consequences of their externalizing impulse. The current moment may be an intensification of an old pattern rather than a rupture into something unprecedented. We are not watching a new movie; we are watching a reboot of a very old franchise, with better special effects.

VIII.

Where does this leave the practitioner who actually needs to use these tools and has a deadline?

The Pokédex approach—stable assignments of models to tasks—oversimplifies a volatile landscape and mistakes provisional heuristics for durable truths. But the rejection of all systematization in favor of pure improvisation is equally untenable, a luxury available mainly to those without throughput requirements or accountability structures.

The defensible position is uncomfortable because it offers no formula. It requires holding multiple recognitions simultaneously: that models have differing capabilities at any given moment, but those capabilities shift; that workflows can capture useful patterns, but patterns expire; that judgment cannot be fully externalized, but some externalization is appropriate and even beneficial; that fluent output is not the same as correct output, but fluency is not disqualifying either; that the desire to escape the slog of being human is understandable and ancient, but the slog is often where meaning actually lives.

This is not a methodology. It is a stance—one of provisionality, attention, and calibrated suspicion. It asks practitioners to be responsive to what the tools are doing now rather than what they did before, to maintain oversight even when the outputs seem fine, to notice when systematization is serving genuine needs and when it is serving the wish to stop thinking.

IX.

The social media thread that prompted this reflection is neither as naive as its critics suggest nor as useful as its format implies. It captures something real—that different tools have different affordances—while overstating the stability of those differences. It serves a pedagogical function for newcomers while potentially misleading them about the nature of the expertise it models. It optimizes for the platform while losing nuance to that optimization.

The extended critique of such threads has its own limitations. It can romanticize improvisation, privilege contexts where artisanal attention is possible, and perform its own kind of status-seeking through the fluency of its skepticism. The move from "here is a Pokédex" to "we have met the enemy and he is us" is intellectually satisfying but risks becoming its own formula—a grimoire of critique rather than a grimoire of prompts, but a grimoire nonetheless.

What remains, after the arguments and counter-arguments have run their course, is the recognition that these tools are genuinely new in some respects and genuinely continuous with old patterns in others. They enable new kinds of externalization while manifesting the ancient desire that drives all externalization: the wish to be spared the weight of judgment, the hope that the hard parts of being human might be made easier or optional.

They cannot be made optional. The tools change what can be delegated but not the fact that delegation is a choice requiring judgment about what should be delegated. The slog migrates upward—from arithmetic to interpretation, from filing to governance, from prompting to deciding what should be asked at all—but it does not disappear. You no longer have to do the arithmetic, but now you have to audit the arithmetician. You no longer have to write the first draft, but you have to verify that the drafter did not hallucinate a court case.

The Pokédex was never going to save us from that. Neither will the critique of the Pokédex. The only thing that helps is the willingness to keep paying attention, even when—especially when—the machine makes it feel unnecessary.