The Molecule, Day Three: Combustion and Exhaust

There’s a narrow window in Portland traffic where you get an unimpeded straight shot through I-84 into downtown, and I missed that aperture this morning, getting carried along a viscous stream of cars across the Morrison Bridge, down Naito Parkway, and into the $17 a day garage where optimism for a lower-level parking spot quickly evaporates, and you end up grateful for something on the seventh floor. I encounter juror #31 at the elevator. I recall she works in the meat packing industry and make a quip about how she knows what precedes the sausage machine and now she’s in the gears of the judicial grinder. She appreciates the joke.

It’s a remarkably clear and sunny day, and the 15th floor of the courthouse affords a glorious view of Mounts Hood and St. Helens. “We don’t have natural elevation in Houston,” I tell no one in particular. “We call it ‘The Heights,’ because it's 100 feet above sea level.” My inner Peggy Hill and Dale Gribble nod in appreciation. We 37 panelists (three were dismissed yesterday: two with inflexible air travel plans, one with rigid child care needs) squint in the hallway, arrange ourselves like a marching band sans instruments, and parade into the courtroom for the prosecutor’s part of voir dire.

I thought of Anna on the way to the courthouse. She worked as the manager of the fine local game store that two of my friends own. Her husband and father of their four kids shot her in the head. Twice. I didn’t know Anna outside the context of the shop, but when I heard the news it’s as if a curtain had shut out the sky. “Have you been the victim of a crime,” was one of the questions for the panelists yesterday. “My places of residence have been burglarized twice, and I know someone who was murdered by their spouse.” Almost everyone on the panel had been on the wrong end of property crime, “petty theft” which is anything but trivial if you’re left with the mess, but it makes what should be an outlier experience of violation almost ambient. Buffeted by the ripples of homicide? Anything but ambient.

The prosecution begins with a question regarding the safe storage of firearms: do you feel that guns should be locked away when not in use? A unanimous consensus. Then: do you have strong opinions on guns? My hand goes up, and the court is subjected to an unsolicited TED talk.

The American debate on firearms isn't just complicated. It is incendiary. The second amendment on which the right of civilians to keep and bear arms is predicated is really an unusual chimera of statements—a constitutional turducken, if you will, that binds citizens, weapons, and militias together with 18th-century legalese in a way that's either brilliant or monstrous depending on your perspective.

The Dred Scott decision that disenfranchised an entire population rests on the inflammatory pillar that Black citizens would be able to pack heat, no militias required. While that ruling was overturned, Heller made the decoupling a precedent, while McDonald and Bruen further whittled a square peg to be forced into a round hole, with the National Firearm Act as a coat of lacquer by prohibiting automatic weapons and explosives.

The prosecutor stops me there, which is just as well. Moving onto the Gun Control Act which defined who isn't allowed to possess firearms probably would have been a match tossed into the gas tank of the case. I do get to mention that as a volunteer range coach with the Clackamas County Sheriff's Office, I teach people to not be the next Alec Baldwin, because shooting someone is ludicrously easy, while proper firearm handling requires training.

I can so totally see my number on the defense's strike list.

The next question. What interactions have you had with law enforcement, good or bad? One of the two Black panelists recounts the story of how he and two of his friends were detained, cuffed in the back of a police cruiser, because they looked like the trio who had stolen a car. My internal monologue: Profile much? They were on foot. Dude, where's the car? Haebius carpus?

I keep my mouth shut.

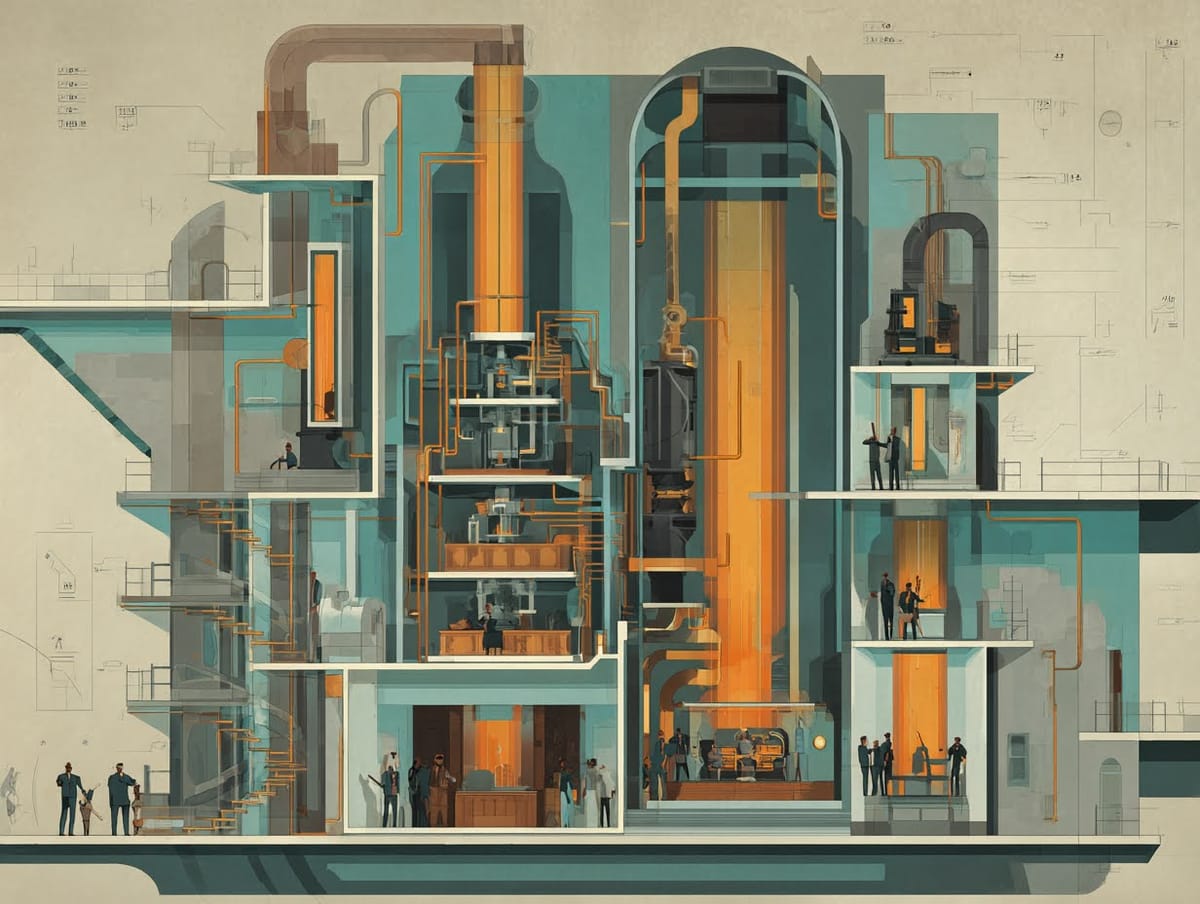

Voir dire concludes, the panelists get a half hour break while the machinery clicks and churns. Is it too much of a shortcut to say that I'm not on the jury? I message Nancy to let her know I'm coming home.

There's a tacit understanding that not getting picked for a jury is a form of "losing." You spent three days in service of the state, paid for downtown parking, ate overpriced salads, floated in the fuel tank—and the machine rejected you. But that's not losing. That's not winning either. It's the mechanism working as designed: identifying molecules too volatile for the reaction it needs. Some of us are too charged. Some of us are too candid. The machine can't use us, but it needed to test us first. That is literally showing up, as a citizen should.

Too reactive and still spitting neutrons, the molecule exits the machine.