The Missing Quadrant

Why TTRPGs Struggle With Kind Chaos

Mapping the Emotional Landscape

If we plot tabletop roleplaying games along two axes—order versus chaos and kind versus mean—we get four quadrants that describe most of the hobby's emotional territory. And when we look at what games actually occupy those spaces, one quadrant stands conspicuously sparse.

Kind + Order (upper left): This space is well-populated. Ryuutama, Golden Sky Stories, Wanderhome, and the gentle side of Powered by the Apocalypse games live here. These are pastoral experiences, cozy fantasies, games about healing and building. The chaos is minimal, the stakes are personal, and the tone is warm.

Mean + Order (lower left): Classic dungeon crawlers and tactical games occupy this space. The rules are clear, the challenges are fair, but the world doesn't particularly care about you. Old-School Essentials, GURPS, traditional D&D—these games have structure, but survival isn't guaranteed and sentiment isn't built into the system.

Mean + Chaos (lower right): This is well-served territory. MÖRK BORG, Paranoia, Alice is Missing, various horror games—they thrive on unpredictability, betrayal, cruelty, and the understanding that things will go badly. The chaos isn't safe, and that's the point.

Kind + Chaos (upper right): This quadrant—the space where disorder reigns but nobody gets genuinely hurt, where everything goes wrong but everyone's fundamentally okay—is strangely underpopulated in TTRPG design.

This is peculiar, because the rest of our media landscape is full of kind chaos.

The Tradition We're Not Translating

Kind chaos is everywhere in film and television:

- Inspector Clouseau bumbles through investigations, destroying everything, somehow succeeding

- Inspector Gadget's incompetence is offset by Penny and Brain, who quietly save the day

- The Ladykillers, A Fish Called Wanda, Bottle Rocket—heist comedies where elaborate plans collapse spectacularly

- Bottom, The Young Ones, Withnail and I—dysfunctional loyalty and continuing despite evidence

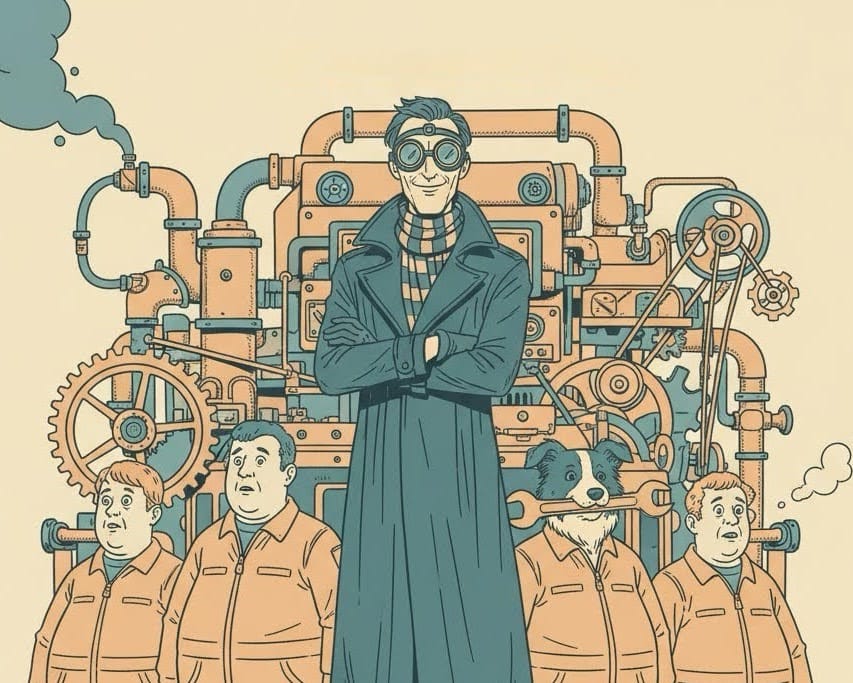

- The entire Wes Anderson filmography—elaborate failure rendered beautiful and safe

These stories share a formula:

- Characters are lovably incompetent

- Plans fail in elaborate, entertaining ways

- Nobody is genuinely harmed

- Relationships survive the chaos

- There's always another attempt

The tone is anarchic but the underlying emotional contract is safe: you can watch people fail without watching them get destroyed.

Recent examples keep the tradition alive. John Scalzi's Starter Villain gives us competent chaos with a gentle touch. The October 2025 Louvre heist—in which thieves stole $102 million in jewels in seven minutes using a cherry picker, while the surveillance system's password was simply "Louvre"—reminds us that real-world incompetence exists at every level, even in institutions we assume are competent. The thieves weren't masterminds: a taxi driver and a garbage collector whose DNA was left at the scene. The museum's security was theatrical rather than functional. The whole affair reads like it was written for a comedy, except it actually happened.

The tradition is old, popular, and emotionally satisfying.

So why don't we see more of it in tabletop games?

Why TTRPGs Resist Kind Chaos

1. Dice create real consequences

Unlike film, where the narrative is fixed, TTRPGs generate outcomes procedurally. When you roll dice, someone has to adjudicate what happens when you fail. The natural instinct is to make that failure mean something—loss of resources, injury, setback, death.

Most game systems are built around meaningful failure: your roll matters because success and failure lead to genuinely different outcomes, and failure usually costs you something.

To make chaos kind, you need to actively resist this instinct. You need mechanics that say "failure is entertaining and propels the story, but doesn't harm you." That's harder to design than it sounds.

2. Players expect competence fantasies

TTRPGs emerged from wargaming, where tactical mastery matters. Most of the hobby's DNA assumes players want to:

- Get better at things

- Optimize builds

- Make meaningful choices

- See skill rewarded

- Progress mechanically

Even narrative games often reward clever thinking, dramatic choices, or system mastery.

A game built around sustained incompetence fights against player expectations. People often come to the table wanting to feel effective, not adorably useless. Designing a game where incompetence is the premise requires explicit framing and player buy-in.

3. Comedy is culturally suspect

The TTRPG community tends to take games seriously as art, which means comedy games often get treated as:

- Lightweight

- Not "real" RPGs

- Party games rather than campaigns

- Lacking depth

This isn't universal—Paranoia has been around since 1984, Toon since 1984, Fiasco since 2009—but comedy games are often positioned as palate cleansers between "serious" campaigns rather than substantial experiences in their own right.

And when comedy games do get designed, they tend toward the mean + chaos quadrant (backstabbing, humiliation, schadenfreude) rather than kind chaos, because cruelty is easier to mechanize than warmth.

4. Chaos without stakes feels pointless

One of the core challenges of kind chaos is: if nothing bad can happen, why do we care?

Traditional game design wisdom says tension comes from risk. If characters can't be meaningfully harmed, if failure doesn't accumulate consequences, if every session resets—what's the point?

This is a real design problem. Kind chaos games have to generate investment through something other than stakes. Usually:

- Relationships (we care about the characters' dynamics)

- Pattern (the formula itself becomes comforting)

- Comedy (watching the Rube Goldberg machine fail is the entertainment)

- Expression (playing incompetence well is its own skill)

But these are subtler engines than "your character might die," and they require more sophisticated design.

5. Safety tools feel at odds with chaos

Modern TTRPG design has increasingly incorporated safety mechanics—lines and veils, X-cards, consent checklists. These are important and valuable.

But there's a design tension: chaos implies unpredictability, while safety implies boundaries.

Kind chaos has to somehow be chaotically safe—unpredictable in detail but reliable in emotional outcome. That's a difficult balance. The chaos can't be so wild that it breaks the safety, but the safety can't be so rigid that it kills the chaos.

Few games thread this needle well.

What Would Kind Chaos TTRPG Design Look Like?

If we wanted to populate the kind chaos quadrant, what would those games need?

Mechanical foam-padding

Some explicit system that says: "Failure is spectacular but harmless." This could be:

- Explicit "cartoon physics" rules

- Reset mechanics between sessions

- Injury systems that are cosmetic rather than debilitating

- Clear genre conventions that protect characters

The game needs to promise that chaos won't become trauma.

Embracing incompetence

Rather than progression systems that reward improvement, these games might:

- Cap stats at low levels

- Make failure the expected outcome

- Reward entertaining failure rather than success

- Have no advancement mechanics at all

- Let players get better at being bad (expression rather than optimization)

The game needs to celebrate characters who don't learn.

Episodic structure

Instead of campaign arcs with rising stakes, kind chaos games often work better as:

- Self-contained sessions

- Sitcom-style repetition

- Reset buttons between episodes

- No persistent consequences

- Comfortable patterns

The game needs to make continuation the victory condition.

Asymmetric competence

Many of the best kind chaos media feature competent sidekicks who quietly fix things:

- Penny and Brain (Inspector Gadget)

- Kato (Pink Panther)

- The actual professionals (every heist comedy)

A TTRPG could mechanize this by:

- Giving NPCs or pets narrative authority

- Creating asymmetric player roles (one competent, others bumbling)

- Making "the straight man" a mechanical position

- Using GM-less rules where one player enables, others chaos

The game needs someone to be competent so everyone else can safely fail.

Non-cruel comedy

The humor has to come from:

- Misunderstandings (not malice)

- Mechanical failure (not character flaw)

- Elaborate disasters (not humiliation)

- Pattern recognition (not surprise betrayal)

The game needs to be funny with characters, not at them.

Why This Matters

The kind chaos quadrant isn't just missing—it's needed.

Many players are exhausted by:

- High-stakes campaigns

- Optimization pressure

- Grim darkness

- Permanent consequences

- The emotional weight of "meaningful choices"

And while cozy games serve some of this need, they don't serve all of it. Sometimes people want:

- Energy (chaos provides this)

- Laughter (kind chaos especially)

- Low pressure (no optimization required)

- Continuation (episodic comfort)

- Permission to be bad at things

The tradition exists in other media. Players already love Inspector Clouseau, Wes Anderson films, bumbling heist comedies, and absurdist sitcoms.

Translating that emotional register into TTRPG form isn't impossible—it's just surprisingly rare.

Examples That Get Close

A few games venture into this space, though none fully commit:

Fiasco creates chaos and comedy, but leans into noir cruelty. Things go badly and people get hurt (emotionally if not physically). It's brilliant, but it's not particularly kind.

Honey Heist (Grant Howitt's one-page game about bears robbing a convention) gets the tone right: absurd premise, guaranteed chaos, inherently silly. But it's a one-shot joke rather than a sustainable framework.

Goblin Quest lets you play incompetent goblins who die constantly—but the dying is the joke, which tips slightly toward mean. It's affectionate, but the goblins are disposable.

The Witch is Dead (Grant Howitt again) has you playing small animals avenging their witch—charming, but brief and bittersweet rather than episodically comforting.

Crash Pandas (about raccoons driving cars badly) gets close: silly, chaotic, kind. But it's more about the absurdity of the premise than sustained exploration of lovable failure.

There are hints and gestures, but few games fully commit to sustained, episodic, mechanically safe kind chaos.

The Design Challenge

Creating a kind chaos game is genuinely difficult:

You need to make failure entertaining enough to sustain multiple sessions without:

- Letting it become mean

- Making it mechanically pointless

- Removing player agency

- Boring people with repetition

- Demanding actual incompetence from players (which isn't fun)

You need to build safety into the system without:

- Making it feel padded and artificial

- Removing all tension

- Making chaos predictable

- Breaking the fourth wall constantly

- Explaining the joke

You need to validate incompetence without:

- Making players feel bad about their play

- Removing the desire to engage

- Mocking the characters

- Creating learned helplessness

- Losing narrative momentum

It's a narrow design target. Thread the needle wrong and you get:

- Too mean (Paranoia)

- Too ordered (cozy games)

- Too trivial (party games)

- Too clever (players optimize the chaos)

Thread it right and you get something special: a game where everyone can fail together, laugh together, and come back next week to fail again.

Cultural Context: Why Now?

The missing quadrant feels especially relevant in 2025.

We're living through:

- Optimization culture exhaustion

- Performance pressure (social media, hustle culture)

- Competence anxiety (AI threatening jobs)

- Burnout from constant self-improvement

- The grinding awareness that effort doesn't guarantee success

In this context, media that gives permission to fail harmlessly and continue anyway feels like oxygen.

People are ready for:

- Permission to be amateur

- Stories where trying is enough

- Relationships that don't require perfection

- Patterns that feel safe

- Laughter that isn't cruel

The kind chaos quadrant isn't just underserved—it's emotionally necessary right now.

What We're Missing

Inspector Gadget has been on television since 1983. The Pink Panther films ran from 1963 to 1993. A Fish Called Wanda came out in 1988. Wes Anderson has been making his particular brand of beautiful disaster films since 1996.

We have decades of beloved kind chaos media.

And yet when players sit down at a TTRPG table, that emotional register is mostly unavailable to them.

Not because it's impossible to design.

Not because players don't want it.

But because the hobby evolved in directions that made kind chaos structurally difficult, culturally suspect, and mechanically awkward.

The quadrant isn't empty because it shouldn't be filled.

It's empty because we haven't figured out how to fill it yet.

The Opportunity

For designers, the kind chaos quadrant represents genuine green space:

- It's not saturated with existing games

- It draws on beloved media traditions

- It serves unmet player needs

- It challenges interesting design problems

- It's culturally relevant right now

The games that figure out how to deliver sustained, mechanically safe, episodic kind chaos will be doing something genuinely underserved in the TTRPG space.

Not because they're inventing a new genre—the genre is ancient.

But because they're translating a familiar emotional register into a medium that's been oddly resistant to it.

The players are ready.

The tradition exists.

The need is there.

The quadrant is waiting.

The challenge for designers isn't creating kind chaos from scratch—it's building the mechanical architecture that lets Inspector Gadget, bumbling heist crews, and lovable disasters exist at the gaming table in sustainable, repeatable, systemically kind form.

The ingredients are vintage. The recipe is proven. We just haven't baked it for this medium yet.