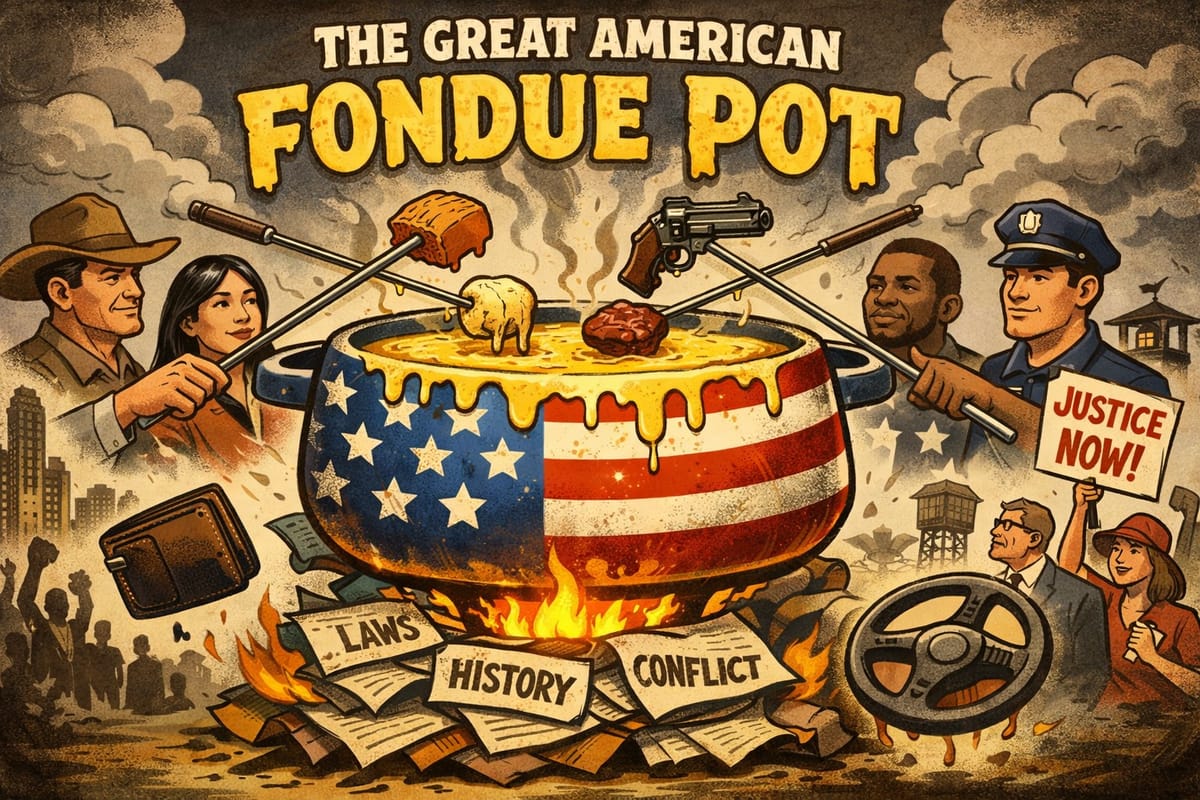

The Great American Fondue Pot

On experiential coating, operational machinery, and the motion that keeps us from burning or freezing solid

I. The Dipping

You get dipped whether you consent or not.

This is the first thing to understand about being American, or being in America, or being adjacent to America in ways that pull you into its field. The pot is already bubbling. The heat was on before you got there. You go in, you come out coated, and the coating doesn't fully wash off.

The melting pot was always the wrong metaphor. It promised dissolution into sameness—E pluribus unum, many becoming one, the alchemy of assimilation producing something new and unified. But that's not what happens. What happens is fondue.

Fondue is communal. Everyone's dipping into the same vessel, their skewers briefly touching in the heated center before withdrawing with whatever they came for—coated, transformed, connected to everyone else who dipped whether they wanted that connection or not.

Fondue requires heat maintenance. Someone has to keep the flame going, and if they don't, it seizes up. But too much heat and it scorches, separates, becomes something acrid. The temperature is always being adjusted, and nobody agrees on who's adjusting it or what the right setting is.

Fondue has rules. If you drop your bread in the pot, there are consequences. The penalties are arbitrary, socially enforced, and everyone agrees to treat them as meaningful.

And fondue is kind of ridiculous. A lot of apparatus and effort to essentially eat melted cheese on bread. The ceremony vastly exceeds the nutritional payoff. You could just eat cheese. On bread. Without the performance.

And yet people keep doing it. Because the doing is the point. (To be fair, melted cheese is a wholly different thing than its solid form—queso for example, but we have a metaphor to maintain…)

II. The Strata

The pot wasn't empty when you got here.

Think of Fordite—Detroit agate—the material formed from decades of automotive paint overspray accumulating on factory fixtures. Layer after layer, color after color, baked repeatedly by curing ovens until it becomes striated, semi-precious, something people cut and polish into jewelry. It's not natural stone. It's the geological residue of industrial process, generations of labor compressed into something accidentally beautiful.

The fondue pot works the same way. You're not being coated in the current layer alone. You're being coated in all the previous layers—every cohort that got dipped before you, their residue still in the mix, chemically transformed by sustained heat into something that can't be decomposed back into original components.

The 1790 Naturalization Act is in there, limiting citizenship to "free white persons." The Chinese Exclusion Act is in there. The Dred Scott layer, where Chief Justice Taney assumed—tellingly—the Second Amendment protected an individual right and argued that Black citizenship was unthinkable precisely because it would let Black people "keep and carry arms wherever they went." The 14th Amendment layer, designed specifically to reverse that, to arm the freedmen against Klan violence. The Mulford Act layer, California banning open carry because Black Panthers were legally armed while cop-watching. The 8.3x disparity in Massachusetts firearms charges. All of it still dissolved in the current mixture.

You can't taste the 1857 layer distinctly from the 1967 layer or the 2020 layer. But they're all in there, contributing to the current viscosity.

III. The Sensors

Here's what the dipping gives you, if you survive it: sensors.

You learn to read rooms. Buses. Checkout lines. Parking lots. You navigate by ear. You track the ambient frequency because you had to, because not tracking it had costs.

As an Asian-American who grew up in Texas, my mental firmware was calibrated early: which spaces were safe, which silences meant what, how to parse the difference between curiosity and hostility in a stranger's gaze. The model minority myth was its own kind of coating—you're acceptable because you're not like those other minorities—which meant learning to sense when that conditional acceptance was being extended and when it was being withdrawn.

A couple of years ago, my wife and I visited Stockholm. On a city bus, a group of African kids got on—just kids, being loud the way kids are loud. And I felt it: the unease among the white passengers. The slight stiffening. The quality of attention that pretends to be inattention.

I wasn't the target. But my sensors picked it up anyway. Because the waveform was familiar. Because I'd spent decades being coated in a differently-seasoned version of the same substance.

The Swedish pot has different ingredients—the folkhem mythology, the studied neutrality, the recent refugee debates, the Sweden Democrats' rise. But the structure of how pots work, how difference gets registered, how bodies learn to sense when they're being othered... that transfers. The coating recognizes itself across borders.

Later, in Helsinki, walking to the Moomin Shop, I passed a yellow utility box with a sticker: FCK RFGS, styled in the Run-DMC logo aesthetic. Taking a format associated with Black American defiance and repurposing it for European nativist sentiment. The fondue pots cross-contaminating in the ugliest way.

I didn't feel outrage. I felt a sad shrug. Recognition. Oh. This too. Here as well. Of course. Or, as the Finns would say, "No niin."

Once dialed in, those sensors never go on vacation.

IV. The Smoke

There's a zone where the frameworks don't survive.

I've written about this before, trying to understand what happens in the seconds before accounting begins. A friend-of-a-friend named Austin Thomerson was killed during an armed robbery at a Houston pawn shop in 2019. He had a concealed carry license. He intervened. He died anyway.

The news reports provide facts. What they can't provide is the phenomenology of the event itself—what Thomerson saw when the door opened, what assessment he made, whether drawing was tactical error or moral necessity or both or neither. Even if surveillance footage were released, it would only provide surrogate legibility. A view from camera position, time-stamped and reviewable. Not the experience of being inside the event when outcome was still undetermined.

N.C. Wyeth painted Gunfight in 1916—four men in a saloon, pistols firing, smoke filling the middle distance. What's striking isn't the action but the absence of readable force. The bodies aren't opposing each other along clean vectors. They're interpenetrating—slumped, folded, grabbing at each other in ways that make it impossible to say who's winning. The smoke doesn't dramatize. It erases.

First: violence. Then: accounting.

During the violence—during the tangle of bodies, the smoke, the seconds when outcome remains undetermined—there are no moral categories operating. No justice. No lessons. Just physics and flesh and incomplete information.

When the smoke clears, accounting begins. Bodies get tagged: victim, perpetrator, armed citizen, bystander. District attorneys decide whether to charge. Social media converts the incident into data points. The gun community extracts tactical lessons. Policy advocates deploy the case as evidence. Everyone wants the death to mean something.

That conversion—from event to meaning—happens fast. And everyone reaches for frameworks that were built after the smoke, trying to apply them to the zone inside it.

The frameworks don't fit. They were never designed to.

V. The Powder Keg

Minneapolis, January 2026.

I saw the headline on January 6th: thousands of federal agents being deployed to the Twin Cities for what would become Operation Metro Surge. My first thought was this won't end well.

It didn't.

On January 7th, ICE agent Jonathan Ross shot and killed Renee Good, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen, mother of three, in her car on Portland Avenue. She'd been there as a legal observer, supporting neighbors in an immigrant-heavy area.

Her wife's statement afterward: "We had whistles. They had guns."

That asymmetry—of force, of legitimacy, of who gets to define what happened—is the whole thing in miniature. The federal government says self-defense, says she tried to run him over, says domestic terrorist. The synchronized video analysis from multiple angles says no run-over occurred, says she was turning away. Both sides have footage. Both sides see completely different events.

Because they're not disagreeing about what happened. They're disagreeing about the baseline.

One framework sees the gap between American rhetoric and American reality as the system—the contradiction is constitutive, the cruelty is the point, and appeals to ideals are camouflage. Another framework sees that gap as deviation from the system—the ideals are real, failures are aberrations, and the underlying model remains sound.

They're not arguing about policy. They're arguing about whether the contradiction is accidental or foundational.

Minneapolis became the place where both frameworks collided at high temperature. Three thousand federal agents in a metro area, outnumbering local police five to one. Daily protests, tear gas, flash bangs. A second shooting on January 14th, a Venezuelan man hit in the leg. A federal judge issuing injunctions against retaliation toward peaceful protesters. The DOJ opening an investigation into the governor and mayor. Active-duty troops on standby. The Insurrection Act invoked as threat.

And underneath all of it: the same neighborhood, six blocks from where George Floyd was killed, absorbing another death at the hands of someone with a badge.

The pot boiled over.

The Rhyme

Amadou Diallo. February 4, 1999. The Bronx.

Four plainclothes NYPD officers from the Street Crime Unit fired 41 rounds at a 23-year-old Guinean immigrant standing in the vestibule of his own apartment building. Nineteen bullets hit him. He was holding his wallet.

The officers said they thought it was a gun. They said he matched the description of a serial rapist. They said when they identified themselves as police, he didn't comply, retreated into the vestibule, and reached into his pocket. They said the first officer fell backward off the steps, and the others thought he'd been shot. So they opened fire.

Forty-one rounds. At a man holding his wallet. Who had no criminal record. Who was reaching, presumably, for identification. Who was trying to comply.

All four officers were acquitted.

The systems that produced that moment:

The Street Crime Unit itself—an aggressive plainclothes squad whose motto was "We Own the Night," optimized for stops and seizures, operating in high-crime neighborhoods with minimal oversight. The unit was eventually disbanded after Diallo, but the operational logic persisted in other forms. Stop-and-frisk. Broken windows. The throughput metrics that reward contact and suspicion.

The "description"—a Black man in a particular neighborhood, which is to say, almost any Black man in that neighborhood. The suspect pool so broad that "matching" required almost nothing specific. The cognitive frame already primed: threat, weapon, resistance.

The vestibule, the nighttime, the plainclothes—a young man confronted by multiple armed men in street clothes, not uniforms, shouting at him. What does compliance even look like in that moment? What would you reach for if strangers with guns were yelling at you outside your own door?

The fallen officer—one trips, the others perceive gunfire that didn't happen, and the shooting becomes self-reinforcing. Each shot confirms the threat for the next shooter. The cascade is neurological as much as tactical. Once the first round goes, the loss of control locks in.

The acquittal—the jury moved to Albany, away from the Bronx. The legal question was never whether Diallo posed a threat, only whether the officers' fear felt reasonable to people trained to share it. The subjective experience of threat, shaped by every prior layer of training and culture and racial priming, becomes the legal test. The system exonerated itself.

And now Renee Good. Twenty-seven years later. Different city, different agency, different specific circumstances. But the structural rhyme is audible.

A woman in a car. An agent who perceives aggression in what others see as disengagement. The vehicle-as-weapon framing that converts any movement into lethal threat. The immediate narrative construction: she was the aggressor, he was defending himself. The footage that shows something more ambiguous, but ambiguity doesn't survive contact with the operational rulebook.

The pattern isn't that cops—or federal agents—are uniquely evil. The pattern is that the systems—training, incentives, legal standards, racial priming, adrenaline, the speed at which decisions must be made—reliably produce these outcomes. The individual in the moment is almost beside the point. The machine is tuned to see threat. The machine is tuned to respond with overwhelming force. The machine is tuned to exonerate itself afterward.

Diallo's wallet. Good's steering wheel. Both read as weapons by people whose firmware was configured to see weapons.

What haunts me about these cases isn't the malice. It's the sincerity.

Those officers in the Bronx probably genuinely believed, in the moment, that they were about to die. Agent Ross probably genuinely believed Good was trying to kill him. The fear was real. The threat perception was real. The bodies responded to what the nervous system told them was happening.

But the nervous system was lying. Or rather, it was telling the truth about its training, its priors, its pattern-matching heuristics—and those were miscalibrated in ways that made a wallet into a gun and a turning vehicle into a charging weapon.

The experiential trunk: what it felt like to be those officers, to be Ross, in the moment of maximum compression. Fear. Certainty. The body acting before the mind can intervene.

The operational trunk: the systems that installed that fear, that certainty, that hair-trigger pattern recognition. The decades of training that says certain bodies in certain contexts are threats. The legal architecture that asks only whether the fear was "reasonable," not whether it was accurate.

The smoke hides everything. And when it clears, the accounting begins. The accounting found those four officers not guilty. The accounting is still processing Renee Good.

Forty-one shots for a wallet.

"We had whistles. They had guns."

The pot keeps simmering. The strata keep accumulating. And somewhere tonight, someone is reaching for something in their pocket, and someone else is deciding, in a fraction of a second, what they're reaching for.

The systems don't pause to verify. They're not optimized for verification. They're optimized for speed, for threat elimination, for surviving the encounter.

The person holding the wallet doesn't get to optimize for anything.

The system has already optimized against them.

The Militia's Direction

On January 24th, a second American was killed in Minneapolis. This one was armed. A lawful gun owner, 37, no criminal record. DHS says he approached agents with a handgun. Video shows a struggle in the snow, then shots, then more shots after he fell.

The Second Amendment community will not claim him.

Had he been killed by ATF agents raiding his home, he'd be a martyr. Had he died defending his business during a riot, he'd be a hero. But he died confronting ICE during an immigration operation, which means he was a fool who should have known better, someone who "played stupid games."

The unspoken truth: the right to bear arms, in practice, is for people like us, defending things we value, against threats we recognize. When the armed citizen confronts our guys doing our work, the Second Amendment develops exceptions.

This is the layer of the turducken that rarely gets examined. The "well regulated militia" of American history has more often served state power than checked it. Slave patrols. Indian removal. Strikebreaking. Sundown towns. The Klan during Reconstruction, terrorizing the very freedmen the 14th Amendment was supposed to arm.

The guns point down the hierarchy, not up at tyranny. They always have.

When armed volunteers showed up during BLM protests to "protect property," they weren't checking government overreach. They were auxiliary to it. If Minneapolis continues to escalate, we may see armed citizens arriving to support federal operations—"community defense" that defends the operation, not the community.

The man who died today did something different. He showed up armed, apparently, in opposition. And he was killed. And he will not become a symbol of resisting tyranny, because the tyranny he was resisting isn't the tyranny that counts.

The fondue coats everyone. But some people are flavor, and some people are fuel.

VI. The Two Trunks

How do you explain what's happening?

There's a temptation to reach for a single lens. To say it's really about racism, or really about federalism, or really about the legacy of the War on Terror, or really about institutional incentives. But single lenses flatten what they're trying to illuminate. They produce either bloodless systems analysis or ungrounded moral phenomenology.

I've come to think there are two trunks—weight-bearing structures that grow from the same organism but extend in directions that don't share axes.

The experiential trunk asks: What does it feel like to be inside this? What do bodies learn before minds decide?

This is where the fondue pot lives. The coating. The sensors you develop from being dipped. The way an Asian-American tourist can feel Swedish unease on a Stockholm bus. The way a neighborhood can be retraumatized by violence that rhymes with previous violence. The way "we had whistles, they had guns" communicates something that policy language can't touch.

The experiential trunk is phenomenological, embodied, temporal. It deals in residue and recognition. It's what lets you navigate Costco by ear, tracking the ambient hum, performing small ceremonies against randomness. It's what makes you provision against the dark—rice to the pantry, tofu to the fridge—knowing the prayer doesn't work but doing it anyway because the alternative is letting the fear win by default.

The operational trunk asks: Why does this keep happening no matter who's in charge?

This is where the machinery lives. Institutional incentive drift: the system does what it's optimized to do, and ICE is optimized for arrests, not community safety. Speed asymmetry: the first narrative locks in before verification is possible. Eroded trust reservoirs: the baseline assumption has shifted from good faith to adversarial skepticism. Performative polarization: identity signaling crowds out outcome-seeking. Professionalized conflict: de-escalation has no institutional champion because calm doesn't pay. Jurisdictional mismatch: civic-moral rulebooks and operational rulebooks don't recognize each other.

The operational trunk is structural, systemic, indifferent to intention. It explains why permit regimes designed to reduce gun violence produce 8.3x racial disparities in enforcement. Why the 14th Amendment was supposed to arm freedmen against white supremacist violence and instead we got the Mulford Act. Why every reform gets metabolized by the machinery into something that reproduces the original pattern.

Neither trunk can do the other's job.

You can't explain why the Stockholm bus felt that way using institutional incentive structures. You can't explain why ICE has arrest quotas using phenomenology. But any honest account of Minneapolis—or of American belonging more generally—requires both questions to be asked.

VII. The Braid

I volunteer as a range coach at the Clackamas County Sheriff's Office public range in Oregon. I teach new shooters the basics: grip, stance, sight picture, trigger control, muzzle discipline. The four rules. State verification. How not to negligently discharge a firearm.

I tell them: It's ludicrously easy to shoot someone. Applying lethal force as a responsible and accountable armed citizen is a lot, lot harder.

I wrote a training curriculum that begins: "This course is not about tactics, performance, or confidence. It is about not making irreversible mistakes." It ends: "Competence is not confidence. Competence is knowing when to stop."

This is operational work. Measurable outcomes. Students who can safely handle firearms and understand their responsibilities. The facility has maintained zero negligent discharges in civilian courses for decades. The system works for what it's designed to do.

What it can't do—what no training can do—is reach the zone where the smoke hides everything. I teach people not to be Alec Baldwin. I can't teach them not to be in the wrong place when someone else decides to start shooting. I can't prevent murder. I can't make the Grocery Outlet safe, or the MAX station, or the parking garage two miles from my house where someone's blood was washed away on a Friday morning.

And I carry experiential knowledge while I teach. A woman named Anna, manager at a local game store, shot twice in the head by her husband. The friend-of-a-friend in Houston. The memorial at the train station. The ambient hum that never fully quiets.

The two trunks meet in a single person. Operational competence and experiential weight. The training manual and the turducken essay. Teaching accountability standards stricter than those applied to federal agents, while knowing accountability doesn't prevent the zone where frameworks collapse.

That's not contradiction. That's living in the actual situation.

VIII. Stolen Land

A recent exchange with a friend:

"You're going to roll your eyes when I say this, but I agree when they say that no one is illegal on stolen land."

"I agree, and I also roll my eyes. Civilizations run on stolen land. 😁"

Both statements are true. The eye-roll is also true. The grin at the end holds the contradiction without pretending it resolves.

"No one is illegal on stolen land" is historically accurate. The entire apparatus of American immigration law rests on displacement and conquest. The legitimacy of the state to determine who belongs is always already compromised by how the state came to be.

"Civilizations run on stolen land" is also historically accurate. Every border on the planet is the residue of previous violence. The Westphalian system is a mechanism for freezing a particular moment's conquest into "legitimacy" and defending that freeze against future claimants.

The eye-roll acknowledges that the slogan, while correct, often functions as a conversation-stopper. It can become a purity signal that exempts the speaker from engaging with the machinery.

The grin is the fondue recognizing itself. There's no clean elsewhere. No pot that wasn't seasoned with blood. You can roll your eyes at the framing and still operate within a shared understanding that the claim is coherent and has to be engaged.

That's progress. Not scoreboard progress—the line going up, gains permanent, reversals aberrant. Complexity progress. The conversation got harder because it got more honest. More pieces are on the board. The game is more interesting and more difficult.

DEI and CRT placed pieces that can't be unplaced, even when they're being countered. "Structural racism" is now a phrase that has to be actively rejected rather than simply unknown. The concepts entered circulation. You can't un-ring that bell. You can refuse to answer it, cover your ears, prosecute the ringer. But the sound happened.

IX. The Boiling

The pot doesn't maintain a constant temperature. It cycles.

Pressure builds. Surface tension breaks. Liquid spills over the rim. The heat gets cut—or reduced—the mess gets cleaned up, the simmering resumes. Then it builds again.

1968 was a boil-over. 2020 was a boil-over. Minneapolis in January 2026 might be another one, or might be the early bubbles of something larger coming. The boil-overs are destructive, chaotic, often tragic. They're also when the pot's contents get rearranged, when new ingredients get incorporated or expelled, when the flavor profile shifts in ways that steady simmering wouldn't produce.

"This too shall pass" is facile. It implies passive waiting, inevitable cycles, nothing to be done but endure.

"Everything is contested" is active. It says the outcome isn't determined, the pieces are still in play, the game is ongoing, your moves matter even if they don't produce final victory.

Authoritarianism isn't destiny. Neither is liberalism. Neither is surveillance-state consolidation nor "becoming ungovernable." These are plays being made by actors with resources and incentives, being met by counter-plays, and the board state is genuinely undetermined.

That's terrifying if you wanted certainty. It's energizing if you wanted agency.

X. The Motion

I've come to think that irresolution isn't the failure state. Premature resolution is.

If you force synthesis where synthesis doesn't exist, you create pressure. That pressure either deforms the analysis (you ignore data that doesn't fit), deforms the person (you perform certainty you don't have), or deforms the politics (policy gets built on false foundations and produces predictable failures).

But imbalance that's acknowledged as imbalance—that's a system in motion.

Walking is controlled falling. You're never in balance. You're always catching yourself. The forward motion requires the imbalance. If you tried to achieve perfect static balance, you'd stand still. Or fall over.

The fondue keeps bubbling because heat is applied. The perpetual stew keeps developing because ingredients keep going in. The Fordite keeps accreting because the paint lines keep running. None of these systems are at equilibrium. They're all in motion, all processing, all becoming.

The danger isn't irresolution. The danger is stasis—either the false stasis of premature synthesis ("I've figured it out, here's the answer") or the frozen stasis of despair ("nothing can be understood, why bother").

What I'm trying to model is neither. It's continued motion through irresolution. Adding new information, connecting it to what came before, noticing the patterns, pushing back on metaphors when they stop illuminating, asking what else is at work. Each move keeps the thing in motion without pretending to have arrived.

XI. The Unloading

You pull into your driveway. The engine ticks as it cools.

The unloading starts. Rice to the pantry. Tofu to the fridge. Each jar of marinara a small prayer against the dark. You've been doing this long enough to know the prayer doesn't work. The Hollywood garage still happened. The Grocery Outlet is still considering closure. But you provision anyway, because the alternative—not provisioning, not moving, not carrying—would mean the fear wins by default.

Somewhere, federal agents are still conducting operations in Minneapolis. Somewhere, protesters are still gathering in subzero wind chill. Somewhere, a judge is drafting an opinion, a grand jury is hearing evidence, a family is grieving, a narrative is locking in.

The accounting continues. It will continue for years. The strata are still being laid down.

And you're here, in Portland, having been to the range yesterday, buying pet supplies today, carrying all of this in your head while the Great American Fondue Pot keeps bubbling. You'll show up next Saturday to teach another class. Six strangers learning trigger discipline: an older couple, an EMT and his partner, a Black woman, a white guy. Zero politics. Just the four rules and the shared project of not making irreversible mistakes.

The game is still being played. The pieces placed by previous generations are still on the board. The concepts your friend invokes about stolen land are still in circulation. The pot is still being seasoned by every cohort that gets dipped.

Motion, not stasis. Contestation, not resolution.

You carry your provisions inside.

The sensors stay on.

The simmering continues.