The Emperor Protects (The Annual Dividends)

A note on canon, capital, and recurring discourse

"Honey, would you make some popcorn? The Warhammer 40k folks are talking women Space Marines again."

It starts, as it always does, with someone typing the wrong thing into a box.

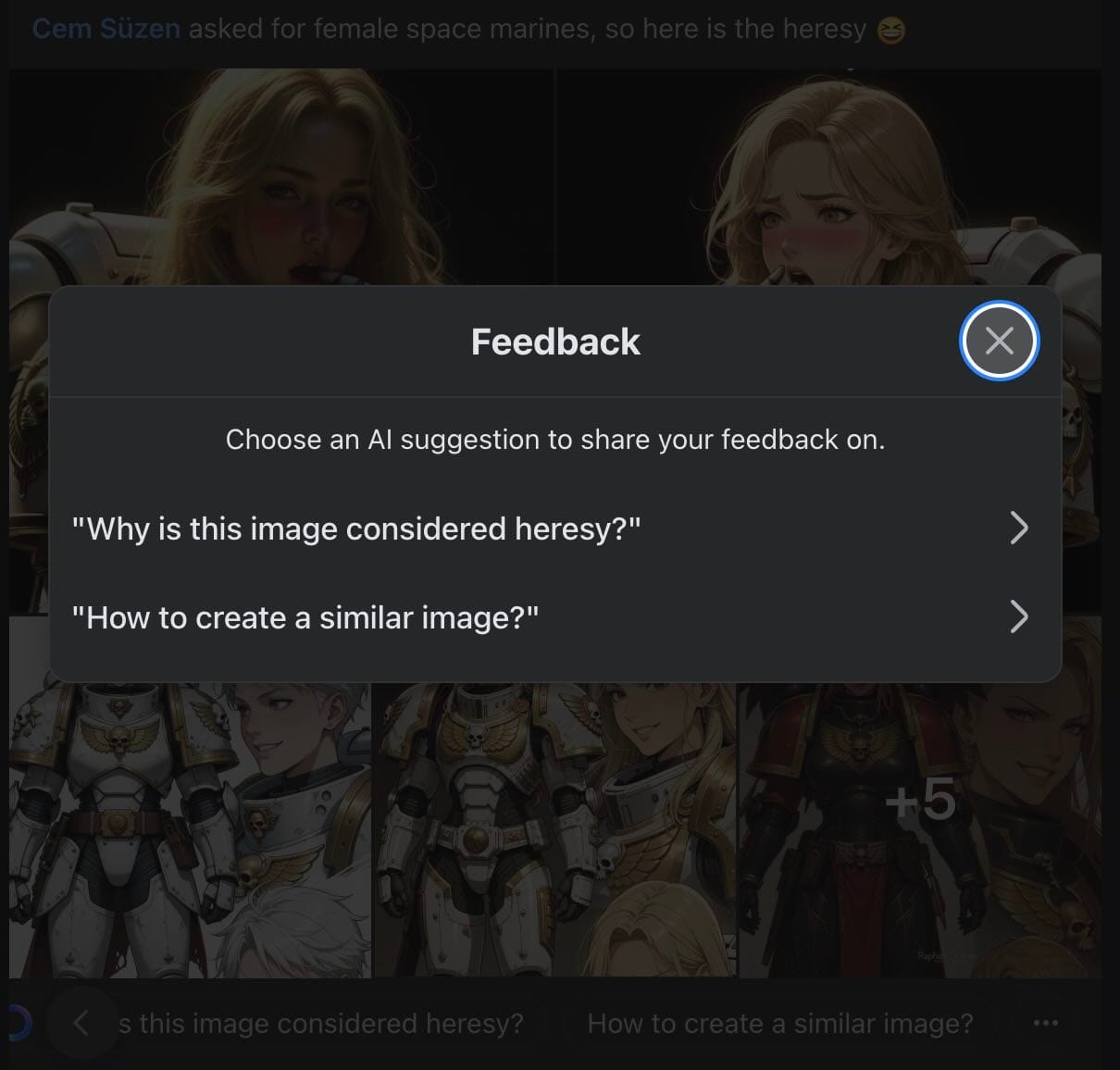

An AI-generated image of female Space Marines appears on social media. Meta's AI helpfully offers two prompts: "Why is this image considered heresy?" and "How to create a similar image?" The algorithm doesn't understand the joke. It doesn't need to. The machinery of reaction is already spinning, because "female Space Marines" is not a design question. It's a shibboleth — a phrase that has accrued social heat far beyond its literal content, reliably detonating the same argument at roughly eighteen-month intervals for three decades.

The interesting thing is not the argument. It's what the argument reveals about the systems underneath it.

Games Workshop is a publicly traded company. It joined the FTSE 100 in December 2024. Its shares rose 38% in the year following. Licensing revenue is forecast to nearly double. These are not the vital signs of a scrappy hobby outfit from Nottingham — they're the metrics of a single-IP corporation whose valuation depends on the stability and expandability of a fictional universe. Every creative decision that reaches the public has already passed through a filter: what does this do to the share price?

This doesn't make the creative work cynical. The writers care. The designers care. The fans care enormously. But it does mean there's a structural gap between the layer where meaning is made and the layer where decisions are approved. Writers and editors operate in narrative time — arcs, themes, consequences that unfold across years or decades. The company operates in financial time — quarters, forecasts, earnings calls. Fans operate in a third register entirely: accumulative time, where a lore detail hardens into identity and a Saturday morning queue outside a Games Workshop becomes a childhood memory that shapes expectations for life.

These three clocks tick at different rates. They measure different things. They define success differently. The system works not because they're aligned, but because they're tolerant of each other — each layer accepting a degree of friction from the others as the cost of coexistence.

In 2017, Games Workshop introduced the Cicatrix Maledictum and split the galaxy in half. Radical on paper. But it was a managed rupture — a spatial fracture that came with codexes, campaign books, and clear guardrails. Same machine, a change of weather. The Imperium persists. Earlier still, they terminated Warhammer Fantasy entirely via the End Times, destroyed the world, and rebuilt it as Age of Sigmar. Fans screamed. Some left permanently. The Old World relaunch exists partly as acknowledgment that the blast radius had lasting consequences. But the company survived, and the lesson was absorbed: controlled detonation beats slow decay.

What Games Workshop will not do lightly is surrender editorial sovereignty. They'll shatter a galaxy. They'll resurrect Primarchs. They'll redraw the timeline. But letting an internal critique of the Imperium actually win — letting a character demonstrate from within the fiction that the system is fundamentally illegitimate — that's the line they've always approached sideways.

Which is what makes Dan Abnett's Constantin Valdor arc so quietly dangerous. Across the Bequin trilogy and the late-stage Siege of Terra novels, Abnett has built something that isn't a villain reveal or a loose thread. It's an alternative Imperium project. Valdor — the Emperor's first Custodian, armed with a weapon that gave him knowledge the Emperor designed him to receive — has apparently concluded that the system failed its own specification. He's not rebelling out of corruption or pride. He's offering design feedback. And he's been assembling the resources to act on it for ten thousand years, from a hidden domain outside both the material universe and the Warp.

This isn't the first time Abnett has run this experiment. Unremembered Empire proposed Ultramar as a contingency Imperium. Eisenhorn and Ravenor explored the Imperium's immune system as a disease. The King in Yellow is the same thesis, iterated to its logical conclusion: what if the Emperor's closest surviving agent looked at the whole edifice and decided it was deprecated?

The Black Library editors are, one suspects, aware of the problem. But this isn't an Iskandar Khayon situation — a narrator who can be quietly de-emphasized. Valdor's arc is anchored to hard artifacts, cross-series continuity, and the prestige of GW's most celebrated author. Retconning it would mean undoing material they just finished minting as sacred text. The most likely outcome is indefinite deferral: keep the thread alive, keep it unresolved, let the anticipation generate engagement without ever forcing a reckoning. That's not a failure mode for Black Library. It's a core competency. Ten years between Pariah and Penitent isn't a bug. It's precedent.

And from the financial layer, it doesn't matter. An unresolved plot thread that generates fan theory videos, Reddit arguments, and long conversations about narrative consequence is arguably more valuable unresolved than concluded. Resolution is a one-time event. Anticipation is recurring engagement.

The same logic applies to the female Space Marines discourse, the female Custodian introduction, and every other periodic eruption. From the investor's altitude, these are not crises. They're rounding errors on a steadily upward-pointing curve — brief fluctuations that, if anything, function as free marketing. Every discourse cycle puts the brand in front of people who might not otherwise have encountered it. The people who leave are outnumbered by the people who discover the hobby exists because the argument reached their feed.

This is not a conspiracy. It's just what happens when a creative enterprise operates inside a publicly traded structure. The commercial incentive is to expand the funnel, and individual lore decisions are tolerable volatility within a growth thesis. Bold creative moves are approved not because they're narratively necessary but because they're commercially sensible and narratively defensible, in that order.

There's a nostalgia trap here, and it's worth naming. In 1989, Bolt Thrower released Realm of Chaos with Games Workshop artwork on the cover. That wasn't a licensing deal. It was a scene overlap — Birmingham-adjacent, subcultural, informal. The band played Warhammer. The art department and the grindcore scene shared pubs. The cultural membrane between the two worlds was permeable enough that nobody thought to formalize what was happening, because formalization wasn't yet required.

In January 2026, Nuclear Blast Records launched Riffs & Realms, an actual play TTRPG series using Mörk Borg with the game's creator Johan Nohr as the GM, featuring musicians from their roster, announced via press release and social media. The participants are genuine enthusiasts. The TTRPG is creatively uncompromising. The overlap between extreme music and dark fantasy tabletop gaming is real. But the infrastructure through which that enthusiasm reaches an audience is fundamentally different — branded, structured, legible in a way the 1989 version never was.

And then there's a third mode, somewhere between the two. Flashgitz's Space King is a YouTube animated series that is transparently, unmistakably a Warhammer 40k parody — Psycho-Warriors instead of Space Marines, Space King instead of the Emperor, holy Globules instead of gene-seed. The serial numbers are filed off just enough. It exists because GW's IP crackdown on fan animators forced creators to choose between compliance and reinvention, and Flashgitz chose reinvention. GW doesn't endorse it, doesn't acknowledge it, and doesn't swing. Not yet. But in 2025, GW filed suit against 280 online sellers, froze assets across multiple platforms, and secured a $10.2 million judgment. The enforcement apparatus is real, well-funded, and active. Everyone involved in projects like Space King knows it's there. They've internalized the constraints so thoroughly that they've pre-emptively designed around them. That's not freedom, but it's not captivity either. It's creative maneuvering under ambient deterrence — the Sword of Damocles as business model.

Three eras, three modes: porousness, partnership, deterrence. The lazy reading is that one was authentic and the others are compromised. The more honest reading is that all three express a similar cultural affinity — metal and dark fantasy belong together — shaped by the systems available at the time. Bolt Thrower didn't have more integrity. They had fewer lawyers, smaller stakes, and a business environment where IP discipline wasn't yet a fiduciary obligation. Judging one as real and the others as manufactured is nostalgia dressed as criticism. The systems changed. The enthusiasm didn't.

And that's the thread that runs through all of it. The hobby persists not because everyone agrees on canon, or because the lore is coherent, or because the company makes the right creative decisions. It persists because it's useful as a social machine. A place to go. A thing to do with your hands. A shared grammar for play that transmits itself intergenerationally — parent to child, friend to friend, store to store — regardless of whatever discourse is burning through the comment sections on any given week.

The supposed flashpoints aren't emergencies. They're scheduled programming. Lore purists invoke canon. Counter-purists invoke vibes. Someone insists it doesn't matter. Someone insists it matters a lot. A moderator locks a thread. Repeat. The Administratum would recognize the pattern: forms filed, tempers vented, nothing actually breaks.

And somewhere, quietly, while the adults argue about whether a fictional institution's recruiting practices align with a forty-year-old sourcebook, a kid picks up a brush, makes a mess of a basecoat, and decides this is theirs now — without knowing or caring why anyone is upset.

That kid is the actual load-bearing structure.

The Emperor protects. But the hobby persists on its own.

Author's Note

"No one reads Playboy for the investigative journalism," said hardly no one ever. Similarly, who:

- accumulates a shelf of deprecated codices

- owns a second-hand copy of original Necromunda

- hoards more Black Library ebooks than common sense permits

- keeps a Goff Rocker that's been unassembled

…just for the game?

I own seven Warhammer 40k miniatures. I have painted none of them. I‘ve been in it for the lore, the systems, and the spectator sport of watching a fandom reliably detonate over the same questions every eighteen months. This essay is written from inside the tent, sitting near the back, sipping tea. The Inquisition has my file. It is flagged as “mostly harmless.”