The Digital Village: From Seahaven to Smartphone

In the 1967 British television show The Prisoner, Patrick McGoohan's Number Six defiantly declared, "I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed, or numbered. My life is my own." That the titular prisoner remained a captive in the Village anticipated our current digital predicament with startling precision.

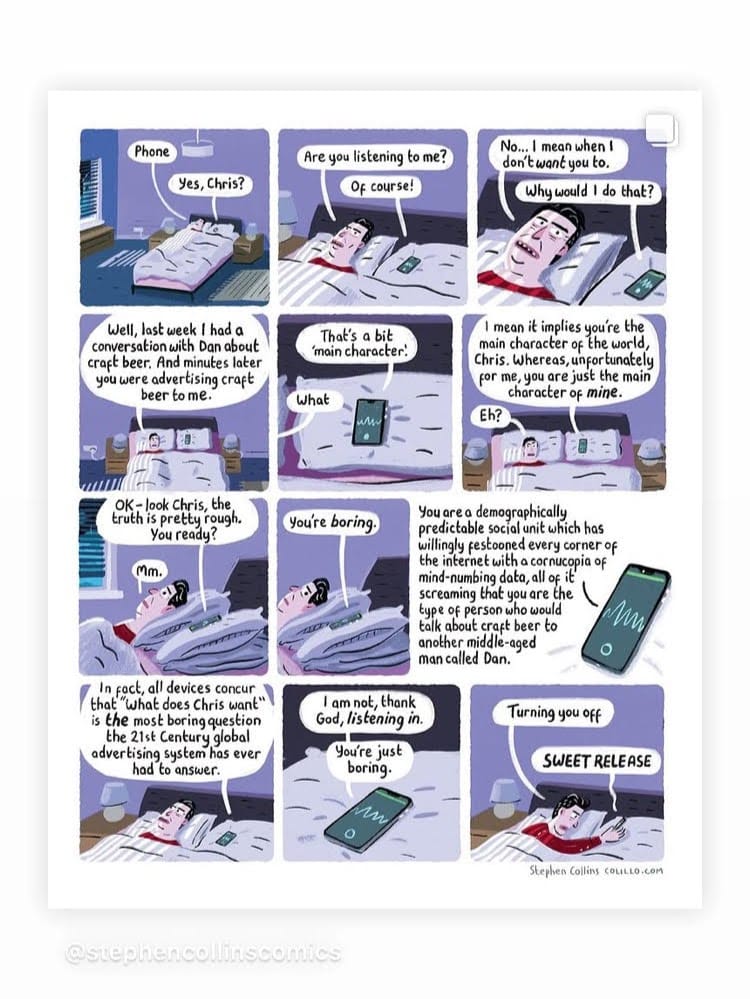

Stephen Collins' comic strip captures the modern evolution of this dynamic with dark humor that makes the critique all the more effective. Chris lies in bed, thinking he's had a personal conversation about craft beer with his friend Dan. What unfolds is the algorithmic revelation that this seemingly intimate moment is actually just another data point in a vast surveillance apparatus.

The phone's deadpan dismissal—"You're boring"—followed by its clinical breakdown of Chris's identity as a "demographically predictable social unit" echoes the Village's cold numerical classification, but with crucial differences: Chris participates willingly in his own cataloguing, and unlike Number Six's captivity, the system transactionally serves Chris's interests even as it reduces his individuality to consumption patterns.

Number Six knew he was imprisoned. He could see the boundaries of his captivity, identify his captors, and mount conscious resistance (when not being bonked by the Rover, the wobbly white balloon enforcer of the Village). Chris, by contrast, carries his Village in his pocket. The boundaries are invisible, the captors are algorithms, and resistance feels not just futile but counterproductive—after all, the system provides genuine value. The IPA recommendations might actually be quite good.

The comic's progression from a casual conversation to the algorithmic mic drop reveals a fundamental shift from the crude mechanisms of traditional authoritarianism to something more nuanced. The Village needed physical barriers and overt manipulation to extract information from an unwilling subject. Our digital systems evolved from a different imperative entirely—not control, but commerce. The surveillance is a byproduct of platforms envisioned to connect people, sell products, and solve genuine problems. We provide data not because we're coerced, but because the trade-off often feels worthwhile: convenience, connection, and personalized experiences in exchange for behavioral information.

When Chris realizes he's not the main character of his own story but merely a persona in someone else's dataset, he's experiencing something that echoes Truman Burbank's gradual awakening to his constructed reality of The Truman Show. But where Burbank could escape the soundstage to the "real world," Chris faces a different problem: the algorithmic analysis of his behavior enables genuinely useful predictions, even as it flattens his individual complexity into demographic clusters.¹ The craft beer conversation that felt personal becomes data that shapes not just advertising, but cultural production itself—what movies get made, what music gets promoted, what conversations get amplified. We're not just being surveilled; we're watching our own diversity get compressed into marketable categories.

The final panel's "SWEET RELEASE" when the phone is turned off suggests both the temporary nature of any escape and the addictive quality of our digital imprisonment. Number Six could rage against his captors because he understood he was captive. Chris can only find momentary relief by disconnecting from a system that has become indistinguishable from modern life itself.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Collins' comic is how it reveals our comfort with a bargain we don't fully understand. We've created systems that provide unprecedented access to information, enable global communication, and offer tools that genuinely enhance human capability. The price—detailed behavioral monitoring—often feels abstract compared to the immediate benefits. This may not be the malicious imprisonment of the Village, but perhaps something more subtle: a trade-off made without full awareness of its long-term implications.

The historical precedent is worth considering. The printing press displaced oral traditions and threatened established authorities. The telegraph collapsed distance while birthing anxieties about the pace of modern life. Each transformative technology has generated fears about loss of autonomy and authentic connection. Some of our discomfort with digital surveillance may simply reflect the refactored growing pains of adapting to new capabilities while whistling past the graveyard of a data-driven dystopia.

Number Six's declaration of individual autonomy feels almost quaint now, but perhaps for different reasons than we initially assumed. He refused to be numbered, but we've moved beyond crude classification to predictive systems that often serve our interests while mapping our behaviors. We're not prisoners demanding freedom from the Village—we're participants in a complex system that provides ephemeral value while extracting lasting costs.

But the question of understanding itself deserves scrutiny. When consent is buried in impenetrable legal documents that could conceal virtually any terms—you could slip excerpts from The Communist Manifesto into a typical EULA and few would notice—the notion of informed consent becomes largely fictional. We click "I Agree" not because we understand the bargain, but because we crave the digital gadgetry.

The Village at least had the clarity of obvious oppression. Our digital systems present us with a more complex psychological trap: we create the paper trails of our own exploitation. Every click, pause, and scroll is logged with timestamps, generating meticulous documentation of our behavioral modification for future auditors. We're not just surveilled subjects—we're unwitting co-authors of the manual for our own manipulation.

This self-inflicted quality fundamentally changes the nature of the harm. As Radiohead observed, "You do it to yourself, you do / And that's what really hurts." Number Six could rage against external oppression, but how do you rebel against a system that has already obtained your voluntary participation? The platforms don't force us to engage—they make non-engagement feel impossible through a combination of genuine utility, addictive design, and social necessity.

Unlike Number Six, we cannot escape to a world beyond surveillance—there isn't one anymore. Instead, we're left with a glowing rectangle on the nightstand, silently collecting data while we sleep, preparing tomorrow's perfectly personalized experience of our own diminished agency.

¹ This analysis focuses on the privileged experience of surveillance as convenience and cultural manipulation. For many others, the same algorithmic systems enable predictive policing, employment discrimination, and targeted sanctions—where demographic categorization carries consequences far graver than personalized advertising.