The Calamine Chat

A Three-Part Meditation on Not Buying a New Bass Guitar

Part I: The Conversation

The itch begins a few weeks before my birthday. Nancy's been playing her Fender Player Mustang bass for about a year now — short scale, flatwound strings, P/J pickup array. It's the sound that anchors the band that she's been playing with, currently gearing up for a video shoot by a local YouTube channel. When she missed a few practices while we were traveling, the band's comment when she returned was simple: "We missed the bass."

That should have been enough information. But during our trip to Helsinki, we found ourselves in two very different music shops.

The first, Musamaailma, embodied Finland's reputation for having more metal bands per capita than any other nation. Five-string basses, six-string basses, extended fretboards like architectural plans, finishes so glossy they reflected the fluorescent lights like weaponized virtuosity. Everything spoke the language of more — more strings, more range, more capability.

A few blocks away, Kitarapaja felt like slipping through a portal into a different philosophy. Here sat a Fender Vintera II Mustang Bass — vintage-correct, single pickup, 7.25" radius fingerboard — and beside it, a phenomenal Eko short scale from the late '60s, priced at €450. The Eko was temptation incarnate: Italian futurism, light as a dream, dripping with character. But the logistics defeated us. How would we get it home? What about a case?

The Vintera, though — that was feasible. Modern manufacturing, proper warranty, available stateside. Nancy tried it. It felt interesting. Different. Then we came home.

Back in Portland, our friend's shop Hank's Music Exchange got in a batch of Aria short scales. Lightweight, easy to play, perfectly nice instruments. Nancy tried one: the cream-colored model that caught my eye on the wall beneath posters for Jesus and Mary Chain and Portishead.

It didn't spark the heart.

So I turned to the machine. Not to a salesperson with commission, not to a YouTube gear reviewer with affiliate links, but to an AI chatbot — patient, incorruptible, with no stake in my wallet. I began asking questions.

Aside from the cost differential and pickup differences, what are the benefits of the Vintera II versus the Player II?

The AI was thorough. It explained neck profiles, fretboard radii, vintage hardware, tonal character. It noted that the 7.25" radius creates a "hugging sensation" while the Player's 9.5" stays "closer to a modern fast neck." It discussed bridge construction, weight distribution, setup quality.

Then I added context: Nancy's tried the Precision bass and found the neck too wide. She prefers flatwounds over metallic roundwounds.

The AI adjusted its analysis. It talked about how flatwounds interact with vintage bridges, how they emphasize fundamental over harmonic content, how the Vintera's solid bridge plate couples string vibration differently than the Player's bent-steel saddles. It was encyclopedic and thoughtful.

More context: Her band has electric guitar with jangle and bite, analog synths, drums, two to three vocalists. Think '90s West Coast indiepop.

Now the AI's analysis shifted toward ecosystem. It described the Player Mustang with flats as a "translator between Motown and Sarah Records," able to underline kick drums, counterpoint synth lines, and converse with melodic guitar hooks. The Vintera II, by contrast, would be a "character actor" — beautiful in tone coherence but potentially constraining in a polyphonic context where the bass functions as secret melody rather than thud.

I mentioned that from my own time playing the Player Mustang, the flatwounds created that almost pillowy thump I associate with early Broadcast records.

The AI caught the reference immediately, expanding on how that early Broadcast tone — The Noise Made by People, Work and Non Work — balances intimacy and detachment. "The flatwound Player Mustang manages the impossible," it wrote, "a polite murkiness."

Then I shared the comment from when Nancy returned to practice: "We missed the bass."

The AI's tone shifted. That wasn't about frequency response or technical completeness, it noted. That was about presence — the way a sound changes the emotional geometry of a room.

Finally, I confessed the real situation: Nancy's Player Mustang had some electrical problems with crackles and pops. East Side Guitar Repair addressed it in February with cleaning and a new grounding wire. The Precision bass has a neck she finds too wide. The Jazz bass is fretless, so it won't work for her friend's band.

The question formed itself: Am I looking for a solution to a problem that doesn't have a statement?

The AI paused — or seemed to, in that way algorithms create the illusion of consideration — and then replied: "That's a beautifully honest question. Most gear purchases are really attempts to restate a feeling rather than solve a problem."

It walked through the diagnostic: The Player Mustang plays well, suits Nancy's hands, fits the band sonically. The only genuine mechanical issue has been repaired. Functionally, there is no problem left to solve.

"Which makes the pull toward the Vintera II less about need and more about the perennial search for affirmation: the sense that there's another level of 'rightness' waiting somewhere."

I laughed at myself. Then I admitted: Maybe the hubby is itching for a roundwound short-scale, but since he can't do that to the spouse's Mustang...

"That's the unspoken subtext," the AI replied. "The husband wants to hear some zing again, but can't very well re-string the wife's bass to scratch the itch."

By then, we'd arrived at the meme that became our conclusion. I shared the Know Your Meme entry for "rifle is fine" — the Ivan Chesnokov copypasta from 4chan's /k/ board, facetiously decrying users who wanted to add aftermarket accessories to perfectly functional Kalashnikov rifles.

The AI understood immediately. "The tool does its job; the urge for an upgrade is emotional, not functional."

I closed the conversation with a realization: There's a parallel story here — how to talk with AI to NOT buy something expensive.

The AI found that funny. It offered to write an essay about it: "AI as calamine lotion for the consumer itch."

Twenty minutes of conversation. $1,300 saved. Rifle is fine. Mustang is fine. Chat was free.

Part II: The Critique

(The following analysis was generated by asking the AI to examine what was missing, minimized, or overstated in the conversation above.)

What's Missing

Nancy's own voice and perspective: The entire conversation filters through the husband's observations. We never hear Nancy's direct thoughts about why she chose flatwounds, her experience with the electrical issues, whether she wants something different, or her feelings about her spouse potentially getting a short-scale.

Financial context: Beyond the "$1,300" price tag, there's no discussion of budget constraints, opportunity costs, whether this is discretionary income or a genuine trade-off, or the household's financial priorities.

The actual playing context: While we know it's for the upcoming video shoot, we don't know how many subsequent shows are planned, whether they're recording, if there are other gear needs for the band, or whether the current setup has failed in any performance situation.

Alternative solutions: The conversation jumps from "new bass" to "no new bass" without exploring modifying existing instruments, renting or borrowing for specific needs, used market options in detail, or the husband getting a different type of instrument entirely.

What's Minimized

The repair history: "Some electrical problems with crackles and pops" is mentioned once and dismissed as "fixed." But this suggests a Mexican-made Fender had quality control issues within a year, the fix might not be permanent, and there could be underlying build quality concerns.

The practical differences: While extensively discussed, the actual audible difference between the Vintera II and Player II in a full band mix is never directly addressed. In a live context with drums, synths, and guitars, the differences might be imperceptible to an audience.

The spouse dynamic: The conversation is framed as the husband's itch but minimizes the possibility that Nancy might actually want something different too, there could be unspoken relationship dynamics around gear spending, and the "joke" about wanting a toy might mask real tension.

The Eko: That €450 vintage Italian short-scale gets dismissed for logistics but represented significantly better value and potentially more character than the Vintera II. The conversation moves on too quickly from what might have been the actual right choice.

What's Overstated

The "pillowy thump" aesthetic: This becomes almost fetishized. While it's a valid tonal preference, the extended meditation on Broadcast's early records positions this as THE ideal bass tone, potentially closing off other valid approaches. Hauntological electronica is its own spectral beast.

The myth-buying framework: While intellectually satisfying, the "every purchase is buying a myth" analysis might overstate the case. Sometimes a tool genuinely improves workflow or sound. The framework becomes so compelling it might obscure genuine practical considerations.

The AI's neutrality: The conversation presents the AI as an "incorruptible" advisor, but the AI is actually performing a specific rhetorical function: validating the user's pre-existing inclination not to buy. It's not neutral — it's a mirror shaped to reflect back restraint.

The "rifle is fine" conclusion: This meme becomes the thesis, but assumes perfect information. What if the Player Mustang's electrical issues return? What if Nancy's playing evolves beyond what that instrument can provide? The certainty of "fine" might be premature.

Vintage correctness: The Vintera II's "era accuracy" is extensively analyzed, but overstates how much this matters for a band playing 1990s indiepop. The vintage aesthetic is being prioritized over actual functional fit.

The Structural Absence

What's most conspicuously missing is any discussion of creation versus acquisition. The entire conversation centers on buying or not buying, but never asks: What new music could be written with current gear? Whether practice time might matter more than equipment? If the "itch" is really about creative stagnation rather than tonal inadequacy?

The conversation performs its own thesis — talking through a purchase until it evaporates — but doesn't question whether the energy spent researching gear might be the very energy that should go into music-making.

The Meta-Layer

The document ends by proposing to write an essay about using AI to avoid purchases, creating a recursive loop: the conversation that was supposed to be about bass guitars becomes about the conversation itself. This is clever, but it also means the original question — what would actually serve Nancy's music best — remains genuinely unanswered beneath all the analysis.

Part III: The Reflection

The critique stings because it's accurate. The original itch — should we get the Vintera II? — transmuted into a philosophical exercise so complete that it occluded the person and the sound at its center.

Nancy's actual preferences, the financial context, the real constraints of her band's live setup — all of those got replaced by metaphor and analysis. Even the act of repair (the grounding wire, the February trip to East Side Guitar Repair) got flattened into symbolic reassurance: the bass is fine, the system works.

And that's where the humor of "AI as calamine lotion" cuts both ways. Yes, the conversation soothed the surface itch. But it also enabled an elaborate avoidance of the harder question: why did the itch appear in the first place?

The answer, I think, is that it wasn't really about Nancy's bass at all. When her band said "we missed the bass," that wasn't a signal of instrumental inadequacy — that was evidence of irreplaceability. The itch was mine: a desire for a new variable in a stable system, for permission to "stir the sandbox," as I put it.

The AI identified this ("the husband wants to hear some zing again") but we both treated it as diagnosis rather than invitation. We never asked: what would satisfy that creative restlessness? Is it really a roundwound short-scale? Or is it a new song, a different arrangement, a willingness to use the instruments already in the room more imaginatively?

The extended meditation on Broadcast's "pillowy thump" was, I now see, aesthetic projection. It's easier — and more intellectually satisfying — to talk about the idea of tone than to ask what Nancy's friends actually need in their combined frequency spectrum. It's easier to romanticize flatwounds than to interrogate whether the band's arrangements might benefit from a sharper edge somewhere.

The AI's closing observation about the absence of creation might be the most useful. The entire dialogue rehearsed the grammar of acquisition: model comparisons, tonal philosophy, logistics, moral restraint. But it never paused to say: What new song wants to be written? What does the band need next?

The gear talk became what the AI called a "displacement ritual" — a way to process creative inertia without naming it. And here's the uncomfortable part: even this essay, this elegant recursive structure we've built, might be another layer of that same ritual.

We're now talking about talking about talking about gear, which is increasingly distant from:

- Nancy's hands on strings

- The next band rehearsal

- The live gig that prompted this whole question

- What song wants to be written

The modern condition of artists who have learned to sublimate creativity into research. The AI becomes a secular confessional, a therapeutic monologue that redirects consumption energy into articulation. It's useful, yes. It saves money, certainly. But it can also become its own form of procrastination — sophisticated analysis as a substitute for making the thing.

There's a line from your own work in How to Hate the Game: "Systems evolve toward maximalism until the people inside them rediscover the pleasure of constraint." The two music shops in Helsinki represented that thesis and antithesis. Nancy's Player Mustang — short-scale, four-string, flats — was the synthesis: an artifact of sufficiency in a world obsessed with more.

But sufficiency, I'm learning, is hard to sit with. It offers no next move, no upgrade path, no narrative of progress. It just asks you to use what you have — deeply, inventively, until you've exhausted its possibilities.

And I haven't. Neither has Nancy. We've barely started.

So here's the real conclusion, the one that was missing from the original conversation:

We began by wondering if we needed a new bass. By the end, we'd written an ethics of wanting — and still hadn't asked what the band actually needs.

The answer might be simpler than a Vintera II or an Eko or an Aria. It might just be: more songs. More practice. More willingness to make do and make new.

The AI helped me see that. But the AI can't pick up the bass that's already in the room and see what it wants to say.

That part's on me.

Coda: Leave It to the Human to Throw a Curve Ball

As I typed that final line — "the AI can't pick up the bass that's already in the room and see what it wants to say" — Logic Pro was running in another window on this same laptop. Drums plotted. Arpeggiated Traktor samples cycling through their pattern. The foundation of a tinkly instrumental, awaiting bass and guitar.

The whole meditation on deferral and creative avoidance was happening while I was actively creating. The conversation wasn't blocking the work; it was running parallel to it, like two apps sharing processor time.

Maybe that's what these conversations with machines actually do. Not replace making, not substitute for it, but provide a kind of cognitive background radiation — a way to keep the analytical mind busy while the creative mind works in another room. The talk about gear, about wanting, about the ethics of acquisition — all of that was just the patter, the surface chatter that let the deeper process continue uninterrupted.

The AI wrote thousands of words diagnosing my displacement ritual. It identified the structural absence of creation in our conversation. It noted, with algorithmic precision, that "the energy spent researching gear might be the very energy that should go into music-making."

It was completely correct and completely wrong at the same time.

Correct because yes, gear talk can become an endless loop of deferred action. Wrong because it assumed the loop was closed, that talking prevented making rather than accompanied it. The AI's analysis was two-dimensional: either you're buying gear or you're making music, either you're thinking or you're doing. It couldn't see that I was doing both simultaneously, that the philosophical masturbation about vintage hardware and tonal mythology was just background noise while my hands moved MIDI notes around a grid.

This is the thing machines can't quite grasp yet: humans are annoyingly capable of productive distraction. We can navel-gaze and build at the same time. We can write essays about not buying things while making the things those purchases were supposedly necessary for. We contain multitudes, and some of those multitudes are working while the others are philosophizing about why they're not working.

Or maybe I'm just rationalizing again, building another elegant frame around the simple fact that sometimes you do two things at once, and one of them looks like thinking while the other one is actually building. Maybe the AI was right and I'm in denial. Maybe this whole coda is just another layer of displacement, and tomorrow I'll be back in the shops, running my fingers down the neck of some other instrument that promises to solve problems I don't actually have.

But I don't think so. Because the track is real. The drums are down. The synth is breathing. And tonight, after this essay is done, the bass will go down too.

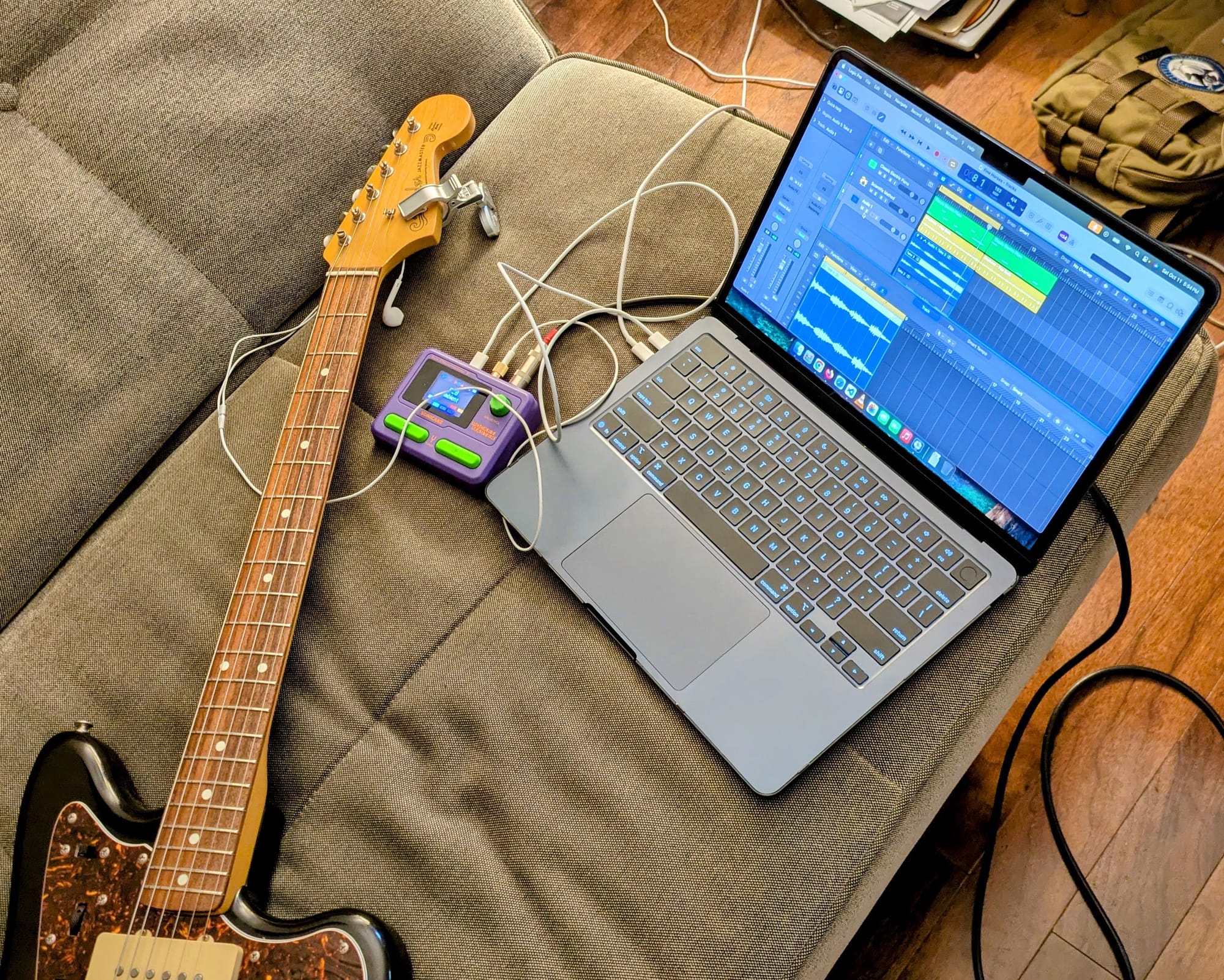

Not Nancy's Player Mustang, as it turns out. That's hers, doing its job with her friends. Tonight it'll be my 1980s MIJ Jazzmaster — butterscotch body, maple neck, recently resurrected at East Side Guitar Repair after almost a decade of hibernation. The same shop that fixed Nancy's grounding issues brought mine back to life. I got it in 1993 for $350, and it just needed a deep cleaning and a recalibration.

The interface? A Sonicake Pocket Master, bought on Amazon Prime Day for around $50. It looks like a cross between Barney the Dinosaur, Evangelion Unit-01, and an Emperor's Children legionary. It sounds better than the $450 Line6 Pod 3 I bought seventeen years ago.

And I can record on the couch. The bedroom is for sleeping. The entire studio fits in my lap: laptop, purple box, guitar. So much for needing a dedicated space.

The song doesn't care which myth I almost bought. It doesn't care about our clever conversation or the AI's careful analysis or my belated revelation about parallel processing. It only cares that I show up.

Epilogue: The Myths Keep Arriving

Earlier today, Hank's Music Exchange put a Tascam 8-track reel-to-reel deck in their window. Complete with mixer. $1,800.

It's probably a 388 or similar — the exact deck we paid $25 an hour to use in 1994, recording a friend's band in someone's garage apartment studio. That $25 in 1994 money is roughly $55 today. Thirty-three hours of studio time equals $1,800. Which is exactly what the deck costs now, except now you'd own a forty-year-old machine that needs maintenance, alignment, and a steady supply of 1/4" tape at $40-50 per reel for maybe fifteen minutes of 8-track recording.

I did different math. That $1,800 would buy an M4 MacBook Air ($1,099), a Focusrite Scarlett 18i20 8-channel interface ($499), and Logic Pro ($199) — with three dollars left over for guitar picks. Infinite tracks, infinite takes, instant recall, no tape costs, no maintenance, and the ability to work from the couch.

The Tascam is gorgeous. It's a monument to a particular way of working, a specific relationship with sound and time and the physicality of magnetic tape. It radiates authentic analog warmth and tape saturation character to anyone who walks by. Someone will buy it and love it and make beautiful music that sounds exactly like 1993.

Nancy's friends already have a Presonus rack-mount digital mixer that goes beyond anything available in 1995. Everyone in the band controls their own in-ear monitor mix through a phone app. In 1995, you got whatever the sound guy felt like giving you through a single wedge monitor, and you were grateful if you could hear the kick drum.

The gear we have now isn't just "good enough." It's demonstrably, measurably better than the equipment that made the records we're nostalgic for. We just don't mythologize it because it works too well and costs too little. There's no story about Steely Dan using a Presonus at A&M Studios in 1977.

The Tascam represents the sound of limitation elevated to virtue. Tape compression, crosstalk between tracks, the need to commit to decisions, the physicality of the medium. All real, all valid if that's the texture you're chasing.

But we're not chasing texture. We're trying to make the shows happen.

Nostalgia wants you to buy expensive reenactments of old limitations while you're sitting on top of quietly superior tools that don't have good origin stories.

The Vintera II, the Tascam deck, the vintage Eko in Helsinki — all beautiful, all myths.

Meanwhile: Nancy's Player Mustang, my resurrected Jazzmaster, the $50 purple Barney box, the Presonus, Logic Pro on a laptop — all function.

And function, it turns out, is what actually lets you make the thing.

Rifle is fine. Jazzmaster is fine. Couch is fine. Presonus is fine.

The myths cost $1,800. The work costs $50 and happens anywhere you happen to be sitting.

And unlike everything that came before it, that last part isn't philosophy.

It's just true.