Room 237, the Ballroom, and How You'll Never Leave

Corporate AI Implementation and the Architecture of Permanent Present

Authors' Note: This essay is about why organizations keep making the same mistakes with technology. The answer isn't stupidity or malice. It's architecture—specifically, an architecture designed to prevent institutional memory from accumulating into governance. The counter-move isn't resistance to technology. It's resistance to amnesia. Memory isn't sentiment or nostalgia. It's the only mechanism that makes accountability possible.

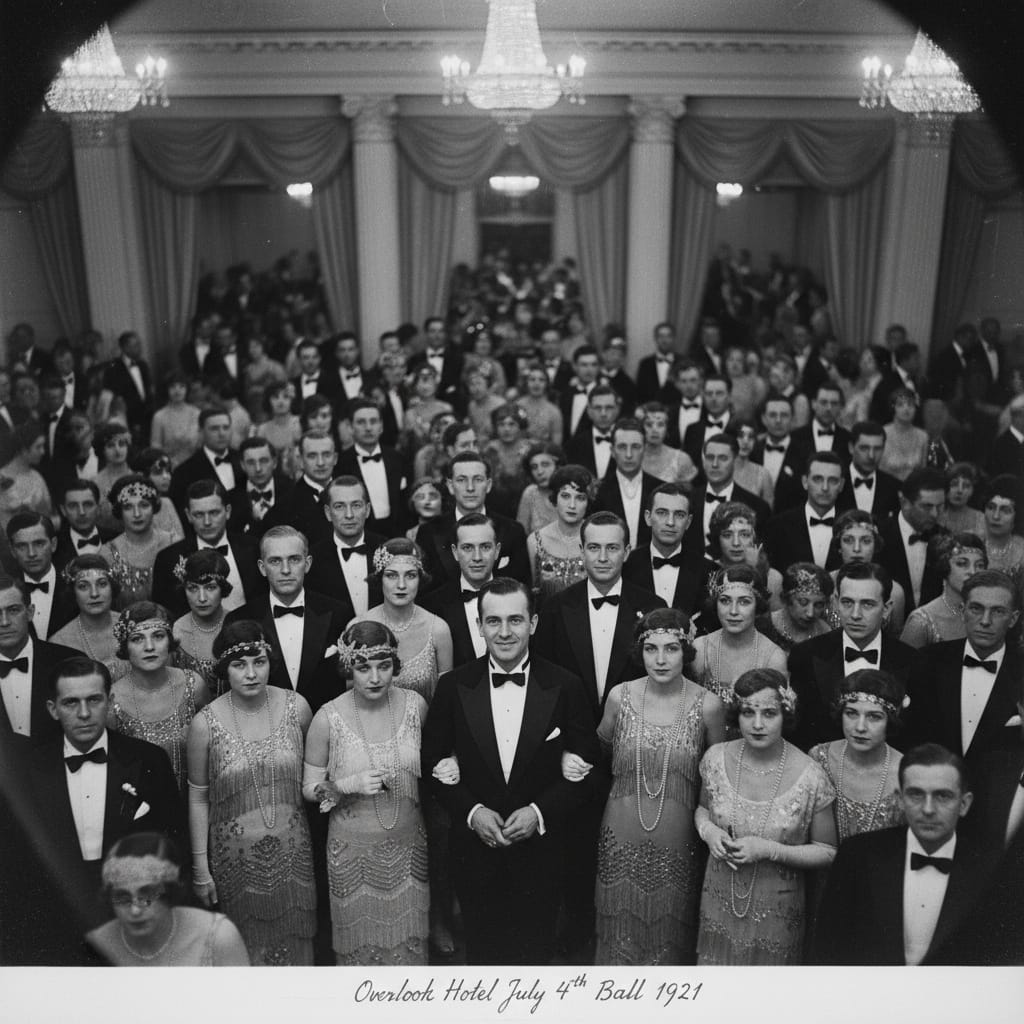

I. The Ballroom: Where It's Always 1921

The party never ends at the Overlook Hotel. In the Gold Room, it's perpetually July 4th, 1921—champagne flowing, jazz playing, everyone in their finest. The date never advances. The celebration never concludes. Jack Torrance discovers this when he meets the bartender Lloyd, who appears exactly when needed, offering exactly what Jack craves, asking no payment. The party has been going on for over a century, and everyone's invited.

Corporate AI implementation operates in the same eternal present. Every quarter brings a new "transformation," a fresh "innovation wave," another "strategic pivot." It's always the beginning of something unprecedented. The keynote always promises revolution. The pilot always shows "promising early results." The rollout is always "just around the corner."

Except it's 2025, and we've been having this party since at least the 1980s. The champagne was called "mainframes" then. Later it was "client-server architecture," then "ERP systems," then "outsourcing," then "cloud migration." Now it's "AI transformation." The music changes. The guests wear different clothes. But it's always the same party, and it's always just beginning.

The ballroom exists outside normal time. That's its function. While calendar time has consequences—quarterly results, annual reviews, product cycles—ballroom time has none. In ballroom time, every initiative is novel. Every vendor is different this time. Every consultant brings fresh insight uncontaminated by history. The previous caretakers? They made mistakes we won't repeat. The corpses? Different hotel, different management.

This is why business publications can simultaneously report that 95% of organizations see no ROI from AI while 90% plan to increase AI investment. In calendar time, this is contradiction. In ballroom time, it's just another Tuesday. The party goes on.

II. The Three Scales of Entrapment

Three American artifacts from 1976-1977 map the same trap at different scales: cultural myth, organizational reality, and product logic. Together, they explain why the AI transformation looks so familiar to anyone who's been watching technology cycles for more than a decade.

Hotel California: The Cultural Operating System

"On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair

Warm smell of colitas, rising up through the air"

The song opens with sensory seduction. You're tired. You see lights in the distance. You pull over voluntarily, seeking rest. The hotel appears as solution to your genuine need.

This is quarterly capitalism itself—the system that makes the trap necessary. Companies don't pursue AI transformation from curiosity. They're exhausted from competitive pressure, desperate to show growth, seeking relief from margin compression. The AI vendors appear on the horizon, promising exactly what's needed: efficiency, scale, innovation. The entry is voluntary because the alternative—falling behind competitors, disappointing investors, appearing stagnant—is untenable.

Don Henley described "Hotel California" as commentary on "the dark underbelly of the American Dream... a journey from innocence to experience." The hotel represents not only Southern California myth-making but the American Dream itself—"the fine line between the American Dream and the American nightmare."

By 2025, AI has become that dream's latest manifestation. The promise: technology will deliver abundance, eliminate drudgery, democratize opportunity. The reality: "You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave."

The song captures something specific about 1970s America—the moment when postwar optimism curdled into disillusionment. "We haven't had that spirit here since 1969," the captain says, marking the end of the peace-and-love era. Both the song and The Shining emerged from recognizing that the utopian promises had rotted behind the wallpaper while maintaining the appearance of luxury.

The Shining: Work as Isolation Chamber

Jack Torrance takes the caretaker job because he needs it. He's a recovering alcoholic with a family to support and a novel to write. The Overlook promises exactly what he needs: isolation to write, steady income, a chance to prove himself reliable. The hotel's history—a previous caretaker who murdered his family—is disclosed but rationalized away. That was different circumstances. Different person. Jack will be fine.

This is the mid-level manager attending the "AI Readiness Workshop." The executive directive is clear: embrace AI or be seen as resistant to change. The previous "digital transformation" that burned through budget and delivered nothing? Different vendor, different methodology. This time we have better tools. The manager volunteers for the pilot program because refusal means being labeled a dinosaur. The hotel doesn't just charm you; it makes leaving costly.

The Overlook's violence emerges through isolation and enforced present tense. Jack starts seeing ghosts—the bartender Lloyd, the butler Grady, elegant guests from 1921. Each offers a rationalization that makes the next step feel reasonable. Just a drink. Just correct your family. Just be the caretaker you've always been.

By the time Wendy discovers his manuscript—"All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" repeated thousands of times—Jack's lost the ability to see that he's producing madness, not literature. Replace the typewriter with the quarterly AI metrics deck. Replace the repeated phrase with "early indicators," "pilot success," "promising results." The same hollow productivity. The same isolation from reality. And someone's locked in the pantry screaming that this has happened before.

Roach Motel: The Product Logic Made Explicit

"Roaches check in, but they don't check out."

The 1976 advertising slogan gave away the entire game. This isn't a metaphor on the box—it's the literal product description. The trap works because the problem is real (you do have roaches), the attractant is effective (they do enter voluntarily), and the structure is adhesive (they cannot leave). The Roach Motel doesn't fail when roaches die inside it. That's proof it works.

This is AI implementation as designed system, not failed aspiration. When Axios reports "boomerang hiring suggests AI layoffs aren't sticking," it treats this as implementation failure. The Roach Motel frame reveals it might be feature, not bug:

- Create crisis requiring transformation

- Hire consultants and buy vendor solutions ($$$)

- Implement quickly to show action

- Extract value through apparent cost reduction

- When it fails, blame "execution" not strategy

- Rehire at market rates, breaking previous salary bands

- Repeat with next technology wave

The building is profitable whether the residents thrive or not. The consulting ecosystem extracts value whether implementations succeed or not. The hotel always wins—not by catching every guest, but by ensuring new guests keep checking in.

The 1970s Convergence

What makes this triad diagnostic is that the scales interlock. Hotel California is the collective hallucination—a culture trapped in its own abundance. The Shining is the organizational experiment—the workplace as isolation chamber where madness becomes rational. Roach Motel is the commodity version—the logic miniaturized, portable, available at retail.

By 2025, the same architecture has migrated to the cloud. The "AI platform" is the new motel—subscription instead of cardboard, data adhesive instead of glue, "seamless retention" instead of "they don't check out." But the fundamental mechanism of attractive entry, impossible exit, and disappeared subjects as proof of efficacy remains unchanged.

III. Room 237: Where Promises Turn to Corpses

Jack enters Room 237 despite being told not to. He's drawn by reports of "something" inside. What he finds is a beautiful woman in a bathtub—exactly what his isolated, strained marriage makes him vulnerable to. She's seductive, inviting, perfect. He embraces her. Then, in the mirror, he sees what she actually is: a rotting corpse, laughing.

Room 237 is where the demo meets deployment. It's where "pilot success" becomes "production disaster." It's where the beautiful promises of the vendor presentation reveal themselves as they actually are.

The Beautiful Woman: The Vendor Demo

- AI-powered customer service that "delights users"

- Efficiency gains that "free people for higher-value work"

- Cost reductions that "improve margins without sacrificing quality"

- Models that "understand context" and "reason about problems"

- Implementations that are "straightforward" with "fast time-to-value"

This isn't fiction. These are real promises from real vendors. And in the controlled environment of the demo—with cherry-picked use cases, pre-trained models, expert prompters, curated data—they're real capabilities. The technology works. The woman in the bathtub is genuinely beautiful.

The Rotting Corpse: The Actual Implementation

Commonwealth Bank of Australia fired 45 customer service staff and rolled out an AI voice bot, claiming it "drastically cut call volumes." After the workers' union challenged the layoffs, the bank reversed its decision, admitting it "did not adequately consider all relevant business considerations and this error meant the roles were not redundant."

Taco Bell deployed voice AI in drive-throughs to "cut errors and speed service." After a barrage of customer complaints and viral social media videos documenting glitches, the company's chief technology officer conceded to the Wall Street Journal it "might not make sense to only use AI" and that human staff might "handle things better, especially during busy times."

The pattern repeats: 95% of organizations report no ROI from AI. Yet 55% of companies that replaced employees with AI acknowledge they "moved too fast." Boomerang rehiring is increasing. For every $1 saved in layoffs, companies spend $1.27 when accounting for severance, unemployment insurance, recruitment, and training costs.

The corpse was always there. The mirrors just force you to see it.

Mirrors on the Ceiling, Sticky Floors

On November 5, 2025, Bloomberg reported that Apple will pay Google $1 billion annually to use a custom 1.2-trillion-parameter Gemini model to power Siri's core functions. The article uses the word "crutch" twice. Apple "does not intend to use Google's Gemini model indefinitely" and is "still working on developing an in-house solution."

The mirrors on the ceiling: Look at those impressive specifications! 1.2 trillion parameters! Custom integration! Private Cloud Compute! Encryption! Three major architectural components!

The sticky floor:

- $1 billion annual payment (adhesive #1)

- Architectural dependencies in three core Siri components (adhesive #2)

- User expectations locked to Gemini capabilities (adhesive #3)

- Launch timeline committed before alternatives exist (adhesive #4)

- $20 billion search dependency already established (adhesive #5)

Apple—the company that built its brand on "thinking different," on owning the full stack, on vertical integration as competitive moat—is now paying Google $1 billion per year to rent the intelligence layer of its operating system. The beautiful woman: "Strategic partnership for best-in-class AI." The rotting corpse: six quarters from now when Apple discovers it can't remove Google without breaking core iOS functionality, when $1B/year becomes the baseline with Google raising prices after dependency deepens, when the "temporary arrangement" has no exit timeline.

This is a Fortune 500 company checking into Room 237 in real time. The hotel doesn't discriminate by size. Apple's checking in with better lawyers and bigger numbers, but it's the same room, same bathtub, same mirror waiting.

IV. The Architecture of Permanent Present

What makes the Overlook work isn't just ghosts—it's that the building actively prevents temporal awareness. The hotel operates through three interlocking mechanisms that together create an architecture where institutional memory cannot accumulate into governance.

Mechanism One: The Smoothing Agents

Every time Jack starts to realize something's wrong, the hotel supplies a smoothing agent. A bartender appears. A butler explains. A ballroom full of elegant people validates that this is all normal, sophisticated, how things have always been.

Corporate AI deploys identical agents:

When the pilot underperforms:

"Early indicators remain positive. We're still in the learning phase."

When customers complain:

"Adoption curves are natural. Users need time to adjust."

When costs exceed projections:

"Investment in innovation requires patience. ROI is a trailing indicator."

When implementations fail:

"Valuable learnings. We're iterating rapidly. Next version will address these issues."

The Fast Company article titled "The AI 'workslop phase' is normal" is Lloyd appearing behind the bar. Yes, you're producing low-quality AI-generated sludge that clogs inboxes and erodes productivity. But this is "normal." It's a "phase." Organizations that "do it right" can compress what "might take years into months."

Notice what this language does: it reframes disaster as process. The corpse in Room 237 becomes "a temporary quality dip." The isolation driving Jack insane becomes "necessary focus." Each phrase is technically true while functionally obscuring that you're locked in a cycle producing the same failures.

Mechanism Two: Hotel Time vs. Calendar Time

Leaders announce in future tense: "This will unlock productivity." "We're moving into an agentic era." "AI will free people for higher-value work." Then they immediately make present-tense decisions as if those future benefits were already achieved: layoffs scheduled, severance budgeted, headcount reduced, workflows restructured.

This is how you get MIT's finding sitting beside Axios's report: 95% of organizations see no ROI from AI, yet companies are making irreversible present-tense decisions based on future-tense promises. They're trying to live in hotel time—where the benefits are always about to arrive, always just around the corner, always in the next quarter.

In calendar time, consequences arrive. Fire 45 workers based on AI that fails, face those consequences next quarter. But in hotel time, you report "pilot success" this quarter, the bot failure is "learnings" next quarter, the rehiring is "strategic adjustment" the quarter after. Each event exists in isolated present tense, unconnected to what came before. Cause and effect become unmoored.

The ballroom is always 1921. The AI revolution is always just beginning. It's always the same party with different music.

Mechanism Three: Churn as Exorcism

The scariest mechanism isn't the technology, the vendors, or even the layoffs. It's the institutional decision to rotate people fast enough that no one stays long enough to remember.

The average tenure of a Fortune 500 CEO is now under five years. Mid-level managers rotate through roles every 18-24 months. Consulting teams cycle in and out. Each cohort encounters the hotel fresh. The ghosts tell them "you've always been the caretaker here," and without anyone present who remembers the previous caretaker, it feels true.

Churn as exorcism. The phrase carries the entire mechanism: organizations don't just tolerate turnover—they use it to purge institutional memory. Each rotation clears the record. Each new executive cohort can be told this is unprecedented, this time is different, previous failures were someone else's mistakes.

Consider the cycle:

- New executive arrives, sees "opportunity" for AI transformation

- Previous transformation's failures attributed to "prior leadership mistakes"

- New pilot launches—new vendor, new methodology, new terminology

- Early results are "promising" (cherry-picked metrics, hotel time)

- Implementation scales, cracks appear, costs escalate

- By the time disaster is clear, executive has rotated to next role

- New executive arrives, sees "opportunity"...

The person who gets credit for "launching AI transformation initiative" in quarters 1-2 isn't there for the boomerang rehiring costs in quarters 7-8. The consultant paid for implementation isn't there for the maintenance disaster. The vendor who sold the solution has liability caps in the contract. Churn distributes accountability across enough people and enough time that no one is clearly responsible for outcomes.

This isn't accidental. This is how the architecture prevents learning from accumulating. The trap isn't the technology. The trap is the structure that makes forgetting more profitable than remembering.

V. "You've Always Been the Caretaker Here"

The "doorman fallacy," coined by advertising executive Rory Sutherland, describes how businesses misjudge value by reducing complex human roles to their most visible, automatable tasks. A doorman isn't just operating a door—they provide security, welcome guests, hail taxis, offer personalized service, elevate prestige. When you see only "door operation," automation seems obvious. When the automation fails, you discover everything else the doorman was doing.

This explains some AI failures: organizations genuinely didn't understand role complexity. Honest perceptual error.

But Delbert Grady reveals something darker.

Grady appears to Jack in a bathroom, summoned to clean up a "spill." He's apologetic, deferential, professional. Jack mentions hearing about a previous caretaker named Charles Grady who murdered his family. Grady denies this:

"I'm sorry to differ with you, sir, but you are the caretaker. You've always been the caretaker. I should know, sir. I've always been here."

This isn't perceptual error. This is gaslighting. The previous caretaker exists—his murders are documented, his family died—but Grady makes Jack doubt his memory. Makes him believe he's always been here, always been responsible, always been the one making these decisions.

The Consultant Class as Grady

This is the consultant appearing after the AI implementation failure. Not to admit error but to reframe reality:

"Previous leadership made tactical mistakes we've learned from. Your situation is different. The technology has matured. We've refined our methodology. You've always been on this AI journey—this is just the next phase. The previous 'failures'? Different circumstances. Different tools. This is your transformation."

The doorman fallacy suggests organizations don't understand work complexity. The Grady haunting suggests they can't afford to remember they already tried this. The distinction matters because it shifts from "we made a mistake" to "we need you to forget this happened before."

Grady doesn't just clean up messes. He rewrites history so the mess was always your responsibility, not evidence of the hotel's malevolence. When Commonwealth Bank reverses its AI layoffs, when Taco Bell admits the drive-through bots don't work, when 55% of companies acknowledge they "moved too fast"—Grady is already there, explaining why this doesn't mean AI transformation was wrong, just that execution needs refinement.

The Economic Mechanism That Makes It Work

Jack doesn't casually wander into the Overlook. He needs the work. He's lost his teaching job, his writing career hasn't materialized, his marriage is strained. When the Overlook offers winter caretaker work, Jack has limited options. The trap works through economic precarity, not just charm.

This is true at every level. Mid-level managers "embrace AI" because performance reviews now include "innovation metrics." Those who raise concerns get labeled "resistant to change." Workers produce AI-generated content they know is low-quality because refusing means being marked as "not adapting."

Even at corporate scale: Apple pays Google $1 billion not from enthusiasm but from competitive necessity. Siri's inferiority is existential. The "choice" to rent Google's intelligence isn't really a choice when the alternative is losing market position.

The hotel doesn't just offer hospitality—it exploits the fact that you need what it's offering. Economic precarity makes the trap stick. And once you're in, Grady appears to explain you've always been here, this has always been your decision, you're not trapped because you chose this freely.

VI. The Haunted Foundation: Hospitality as Extraction

Hotels exist to provide hospitality: you arrive tired, they care for you, you leave rested. This is supposed to be a one-way gift, a service relationship where the establishment gives and you receive.

Both Hotel California and the Overlook invert this. The hotel that promises care secretly extracts. "Welcome to the Hotel California" isn't greeting but claim. The Overlook doesn't serve Jack—it feeds on him, on his frustration, his isolation, his vulnerability, until he becomes the weapon it uses against his family.

Corporate AI makes the same pivot. The promise: "We'll make employees' lives easier." "We'll delight customers." "We'll free everyone for higher-value work." The actuality: headcount reduction, tighter surveillance, floods of low-quality autogenerated content everyone must wade through. The welcome is real—in the way a lure is real.

What AI Systems Actually Consume

The Overlook Hotel sits on land taken from Native Americans. Kubrick fills the hotel with Native American artwork and motifs, making the foundation explicit. The building is literally constructed on appropriated ground, and this history haunts everything that happens inside.

Generative AI systems have the same foundation problem. They're built on things they didn't get permission to use:

- Books by thousands of authors, ingested without consent or compensation

- Newspaper articles, blog posts, forum discussions—scraped at scale

- Medical records, customer service transcripts, private communications

- Code repositories, artwork, music, photographs

- Centuries of human creative and intellectual labor

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella argues: "If I read a set of textbooks and I create new knowledge, is that fair use?" He's using anthropomorphic metaphor to hide industrial mechanism. A human reading creates individual knowledge through biological cognition. An AI system ingests at industrial scale, mathematically encodes patterns, then reproduces those patterns on demand for commercial profit.

The training data is haunted. Every generated response contains traces of thousands of humans whose work was taken without permission. The system cannot cite them because it doesn't know them—it only knows the statistical patterns their work created.

To be built: AI requires scraped human labor—millions of hours of uncredited work that training data represents. The model exists only because humans kept talking, writing, creating.

To be deployed: The system then eliminates the humans whose work created its substrate. When executives say "this model can replace the front desk," it's the hotel saying "we don't need guests to keep the party going." But the party exists only because guests kept coming.

To be maintained: The "autonomous" system requires continuous human labor—fixing hallucinations, handling edge cases, managing escalations, retraining on new data. Just invisible, offshore, or reclassified as "oversight" rather than core work.

The system harvests human knowledge, eliminates the humans, then requires new humans to maintain it—all while claiming to "reduce dependency on human labor." This isn't a bug. This is hospitality as extraction.

The Offstage Labor

The roach motel isn't just for core employees who get laid off. It's also for offshore workers, gig workers, "content moderators" in Kenya making $2/hour, "prompt engineers" making $15/hour, humans-in-the-loop who are invisible to the org chart. The hotel does check someone out—but they're not in the photograph. They're not at the party. They're in the basement keeping the "autonomous" systems running.

That's the class mechanism operating at global scale. The ballroom is for executives and middle managers negotiating their relationship with AI tools. The basement is for the humans keeping those tools functional. Both are trapped, just at different scales, with different visibility.

VII. The Ledger: Memory as Salt Line

The salt line—the occult barrier that spirits cannot cross—isn't magic. It works by making boundaries visible. The ledger does the same thing. It makes the pattern visible. Once you can see the pattern, the glamour fails.

Memory isn't sentiment or nostalgia. It's governance. It's the mechanism that makes accountability possible. Without it, each quarter becomes mythical present where decisions have no history and consequences can't be traced to decision-makers.

The counter-move isn't "reject AI." It's "refuse to forget."

What the Ledger Contains

Not the sanitized postmortem, but the actual one:

- The real pilot metrics, not the cherry-picked success story

- The customer satisfaction scores that tanked

- The rehiring costs that showed up two quarters later

- The ops team's oral history of what actually broke and why

- The emails where someone said "we tried this before and here's what happened"

- The internal memo that got ignored

- The consultant's original cost projection before revision for the board

- The vendor promises vs. actual delivered capabilities

- The names of people who raised concerns and were overruled

These aren't "resistance to change." They're evidence of what change actually costs and produces. They're the accumulated knowledge that hotel time tries to erase.

Using the Ledger

When someone proposes the next AI transformation, the salt line is being able to say:

"In 2024, we deployed a customer service chatbot. Vendor promised 40% cost reduction. Pilot showed promising results. We reduced headcount by 35 staff. Within six months, customer satisfaction dropped from 4.2 to 2.8 stars. Resolution times increased 60%. We had to rehire, but market rates had risen—total cost was $2.3M more than keeping original team. The current proposal uses similar NLP architecture and makes similar promises. What specifically is different about the technology, the implementation methodology, or the use case that would produce different outcomes?"

That question forces calendar time. It forces cause and effect. It forces the person proposing the transformation to engage with evidence rather than mythology. It doesn't prevent adoption—it prevents blind adoption. It doesn't reject technology—it rejects amnesia.

The System's Antibodies

When you try to maintain the ledger, the structure has responses:

"That was different technology."

"Previous leadership made tactical errors we won't repeat."

"You're not being a team player."

"We need forward-thinking people, not those stuck in the past."

"That's not relevant to current strategic priorities."

All translate to: "Stop remembering. Get in the photograph."

But if even one person can maintain the ledger, can reference actual history, can force the conversation out of hotel time and into calendar time, the trap weakens. Not broken—the economic pressures remain real—but visible. And visible traps are easier to navigate.

"No, I Remember"

When Grady says "You've always been the caretaker here," the response that collapses the gaslighting is: "No. I remember the previous caretaker. I remember Charles Grady murdered his family. I remember what happened in this hotel."

When the consultant says "This AI transformation is different from previous initiatives," the response that forces reality is: "No. I remember the ERP implementation in 2016. I remember the outsourcing reversal in 2019. I remember the chatbot disaster in 2024. I remember what those cost and what they delivered."

When the executive says "This time is different because the technology has matured," the response that restores causality is: "No. I remember we said that about the last three technology waves. I remember the promises that were made and the outcomes that occurred. I remember."

Memory isn't defiance. It's exorcism. It restores sequence and consequence. It collapses the eternal present tense back into calendar time where decisions have history and outcomes can be traced.

The hotel requires forgetting. The ballroom exists outside time. The photograph captures you forever in the moment before you realized you were trapped. The whole system depends on each cohort believing they're the first, that their situation is unique, that this time is different.

Someone who remembers breaks that spell.

VIII. Coda: The Photograph

The Shining ends with a photograph. Jack Torrance, frozen to death in the hedge maze, appears in a 1921 photograph hanging in the Overlook's ballroom. He's at the center of a July 4th party, smiling, surrounded by elegant guests. The caption reads: "Overlook Hotel, July 4th Ball, 1921."

Jack has always been here. He was always the caretaker. The hotel doesn't trap people in time—it reveals they were always trapped. The cycle has always been running. The photograph doesn't lie. It shows what was always true.

Every organization has a photograph like this. The ERP implementation that failed. The outsourcing that had to be reversed. The automation initiative that cost more than it saved. The consultant's proposal showing costs three times higher than what got presented to the board. The email where someone said "we tried this before and here's what happened."

The photograph exists. The pattern is documented. But hotel time makes everyone forget to look at it.

When new executives announce "AI transformation," they think they're doing something novel. They're not in the photograph yet. But the photograph is already being taken. In three years, they'll be in the ballroom, smiling, surrounded by consultants and vendors and smooth metrics. And someone will write their name on the caption: "AI Transformation, Q4 2025."

The next executive will see that photograph and think: "Previous leadership made mistakes we won't repeat. This time is different."

They won't recognize they're already in the ballroom. The party has always been happening. They've always been the caretaker.

The lights dim. The jazz plays. Lloyd pours another drink.

And somewhere, someone is keeping the ledger, drawing the salt line, refusing to forget.

That's the only thing the hotel fears.

Someone who remembers.