Riff and Reckoning

Led Zeppelin moves me. Their riffs—molten, feral, ecstatic—hit like a pulse in the chest, a sound that feels eternal yet impossibly alive. But that thunder, as undeniable as it is, wasn’t born in a vacuum. It was built on the grooves of Black blues artists, often uncredited, rarely paid.

To love the riff is to wrestle with its cost. This isn’t just about music—it’s about who shapes what we hear, who gets erased, and what we carry in the quiet rituals of our lives. The system that amplified Zeppelin’s sound isn’t a faceless machine; it’s made of choices, some callous, some blind. And while cries of complicity can grate like a whiny nuisance, they’re not wrong to demand we listen closer.

I. The Thunder That Moves

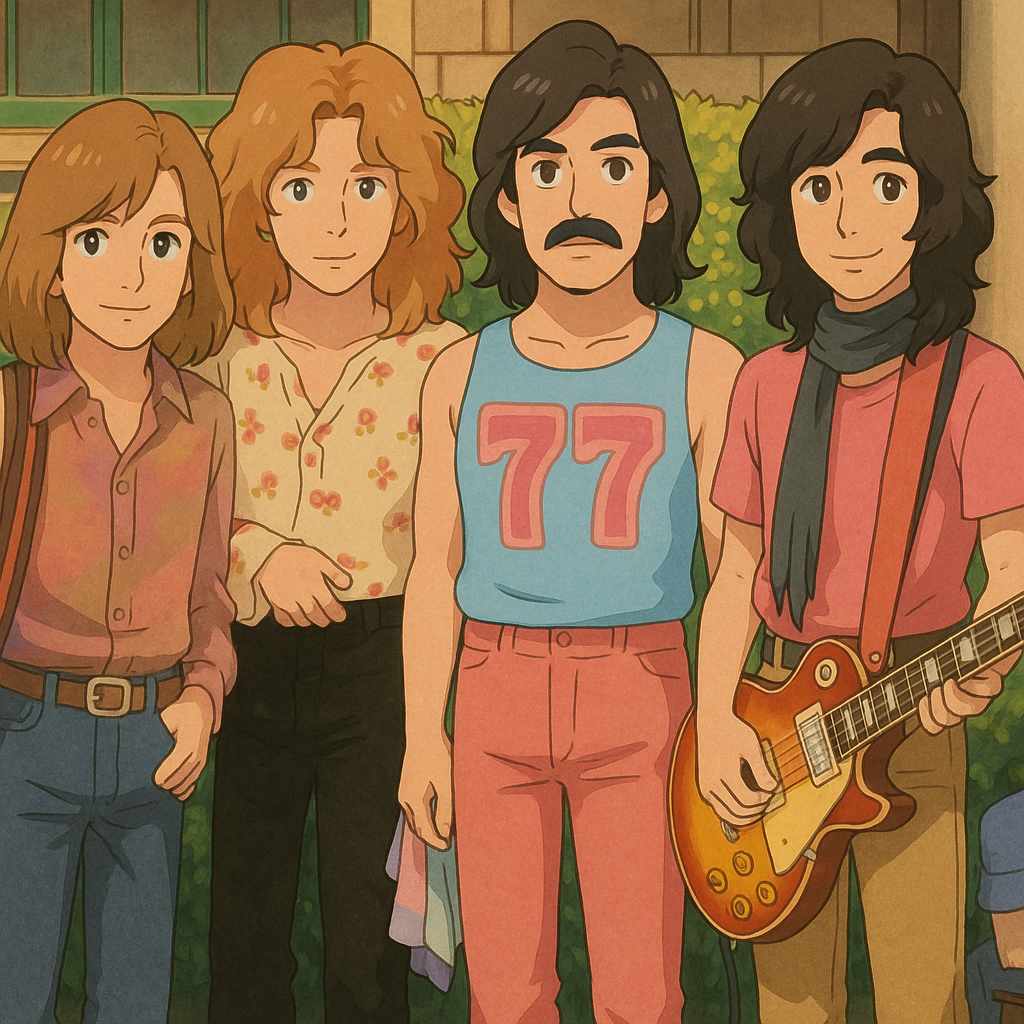

The opening bars of Led Zeppelin I don’t just arrive—they summon. There’s a primal force in those first two albums, recorded in a blur of youth and velocity. Robert Plant, barely 20, wailed with a hunger that felt mythic. Jimmy Page, 24, bent strings into hypnotic loops. John Bonham’s drums and John Paul Jones’s bass were a heartbeat, relentless and raw. This wasn’t just music—it was a trance, a ritual of sexual confusion, domination, and feral joy.

I feel it in my bones, this sound that shakes the room. It’s not just the notes; it’s the swagger, the confidence of kids from working-class Britain—Page from a council estate, Plant from the industrial Midlands—chasing a groove that felt like freedom. Their thunder moves me, and I’m not alone. But here’s the hitch: that sound, as singular as it is, wasn’t theirs alone.

“You Shook Me,” “Dazed and Confused,” “Whole Lotta Love”—these are blues songs, electrified and rebranded, traceable to Black artists like Willie Dixon and Howlin’ Wolf. Zeppelin’s genius was real, but it was also amplified by privilege—access to studios, stages, and a system that welcomed white faces. Their thunder was unique, but it leaned on grooves they didn’t create. To say Dixon or Wolf couldn’t have made the same noise isn’t to diminish them—it’s to name the alchemy of time, place, and power that let Zeppelin’s version roar louder.

II. The System and Its Parts

It’s easy to blame “the system” for this—record labels, radio, promoters—who saw gold in white rock stars repackaging Black blues. But pointing at a faceless machine lets its components off too lightly. Zeppelin didn’t just inherit a sound; they chose to lift it, often without credit until lawsuits forced their hand. Labels like Atlantic knew the blues’ roots but banked on the myth of white originality. Audiences, too, ate it up, rarely asking whose hands shaped the groove.

One could call this complicity, and it’s not wrong. But the word can feel like a mosquito’s whine—insistent, grating, demanding more guilt than insight. Yes, Zeppelin profited from a rigged game, but so did everyone who bought the records, danced to the riffs, or hummed the hooks. Scrutiny isn’t just for the band—it’s for the executives who signed them, the DJs who spun them, and the fans (like me) who loved the sound without questioning its cost. The system isn’t an excuse; it’s a mirror, and we’re all in the frame.

There’s also a flip side. Zeppelin’s working-class roots weren’t abstract—they were visceral. They didn’t inherit power; they chased a sound that spoke to their own hunger. The blues, born of Black struggle, resonated across oceans because it carried universal ache. There’s an accompanying temptation to frame the band as mere thieves when their alchemy—however flawed—was also human. Holding the system to account doesn’t mean erasing the parts that moved us.

III. Gatekeepers and the Ghosts

This dynamic isn’t new. A.P. Carter roamed Appalachia, collecting songs from neighbors and claiming them for profit. Alan Lomax archived Black spirituals and prison chants, marking some “NG” (No Good) in his notebooks. Both were gatekeepers, shaping what survived—Carter for royalties, Lomax for posterity. It’s also too neat to pin the canon on them alone. Labels, markets, and listeners chose what became “America’s sound,” often erasing the Black and rural voices who sang it first.

The ghosts of those voices haunt Zeppelin’s riffs. Clyde Stubblefield’s “Funky Drummer” beat, sampled endlessly, never earned him royalties. The critique demands we name these erasures, but it can overreach, casting every act of curation as theft. Music flows like water—through hands, across borders, between souls. To love Zeppelin’s thunder is to love a current that carried others’ pain. The trick is holding both truths without letting one drown the other.

IV. The Digital Echo

Today, the system looks different but plays the same tune. Spotify pays fractions of pennies per stream, extracting oceans of labor while listeners forget who’s behind the sound. Black artists innovate; platforms flatten; audiences move on. But this loop—innovation, exploitation, forgetting—misses the exceptions. Motown’s rise in the ‘60s, from the Supremes to Marvin Gaye, wasn’t just influential; it was dominant, carving space in a system stacked against it.

Still, the math hasn’t changed. The soil was uneven before the servers spun up. Blaming the algorithm feels righteous, but it’s the choices—by coders, executives, and us clicking “next”—that keep the cycle humming. Accusations of complicity here can feel like noise, whining for purity in a messy world. Yet they nudge us to pause, to ask: whose voice isn’t in the playlist?

V. The Folklore of Two

Not all music needs a stage. In my house, “NG” isn’t just Lomax’s notation—it’s a ritual. My wife learned it cataloging the Sacred Harp Museum, and we toss it around, joking about moments or objects that don’t make the cut. It’s our folklore, a sacred expression of us. Like naming a creaky stair “The Ghost’s Elbow” or calling lightning “sky dragons,” it’s a world built between two. All this is self-indulgent, a privileged retreat from systemic harm. But it’s also true that these private myths are how we make meaning, how we carry the notes of what moves us.

This folklore of two isn’t trivial—it’s sacred because it’s ours. It doesn’t erase the ghosts in the riffs or the system that silenced them. But it reminds me that culture isn’t just what’s recorded or sold. It’s what we whisper, what we name, what we hold close.

VI. The Listener’s Reckoning

So who holds power now? The platforms, sure. The estates, the algorithms, the ones cashing out on loops. But also me, the listener. I feel Zeppelin’s thunder, and I love it. I know it’s built on borrowed grooves, and I owe those ghosts their due. One should pause before clicking “next,” to wonder whose hands shaped the sound. It’s a fair ask, but it can feel like a lecture, a whine that assumes I’m not already wrestling with it.

Listening isn’t passive anymore—it’s a choice. I can’t rewrite the riffs, but I can seek the names behind them. I can amplify Dixon’s voice, share Stubblefield’s story, or support foundations that credit Black artists. The system’s not my alibi, and complicity’s not my chain. I’m here, moved by the music, accountable for what I carry.

Coda: From the Riff to the Room

Maybe the loudest riff started as a whisper between two people. Maybe the truest folklore lives in the kitchen, next to the peanut butter jar, where “NG” means something only we know. Zeppelin moves me, and that’s real. The ghosts they borrowed from move me too, and that’s heavier. The system’s a beast, but its parts—band, labels, listeners—aren’t faceless. And if complicity’s accusations are a whine, it’s one worth hearing, to seek the signal in the noise.

What matters is what plays through the speakers and what I choose to remember. The riff’s a spark. The reckoning’s mine.

Postscript:

This began as a love letter to a sound and became a mirror for its shadows. My thanks to my wife, who taught me “NG,” to the ghosts who shaped the groove, and to the critique that wouldn’t let me look away.