Propaganda's Red Shift and ZTT's Sonic Temple

Forever 20 Minutes into the Future

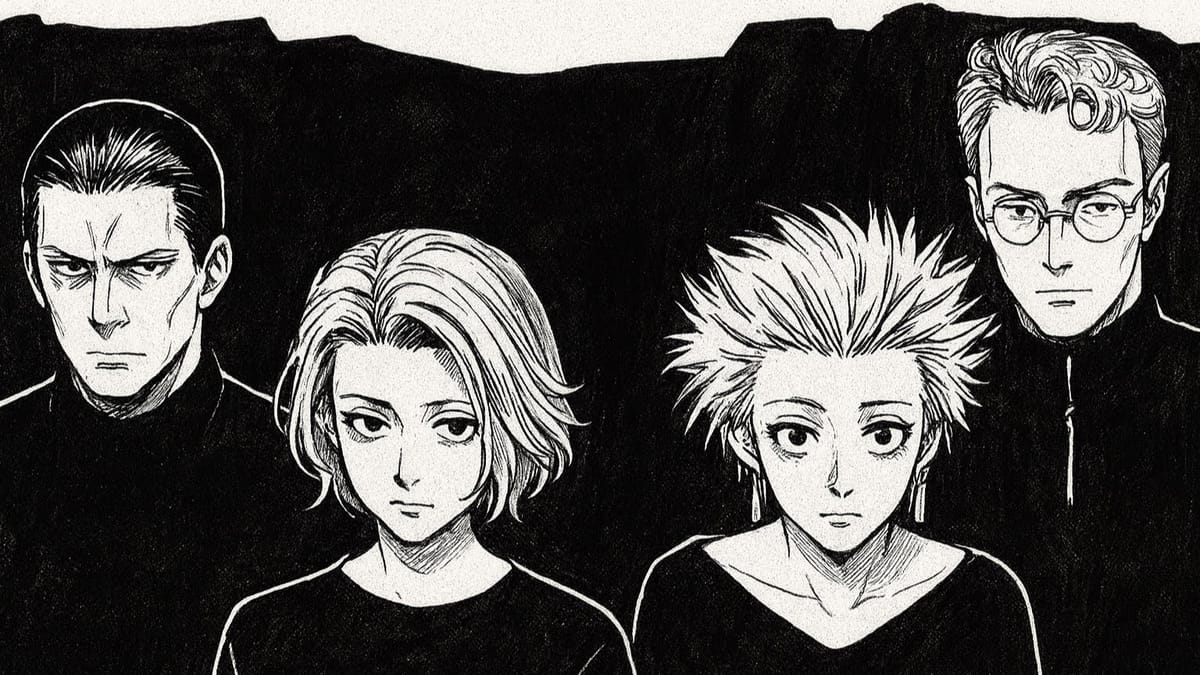

The 2025 release of A Secret Sense of Rhythm, A Secret Sense of Sin: The Complete ZTT Propaganda offers six discs spanning their time on ZTT Records (1983-85), curated by the label's archivist Ian Peel. It includes their 1985 debut A Secret Wish in both "Analogue Sequence" and "Digital Variation" forms, plus rare tracks, mixes, studio material, and video/TV mixes across thematically organized discs: "Secret," "Stahlnetz," "Singlette," "Series," "Studio," and "Stage." This six-and-half hour monument serendipitously arrived to mesh with the author’s early morning musings on The Art Of Noise, robotic blues, and what we felt was the backstaging of Anne Dudley behind the Trevor Horn/ZTT mythology.

I. The Transmission Before the Context

In 1984, encountering The Art of Noise's Who's Afraid? on cassette was like intercepting a signal from cyberspace before anyone had coined the term. William Gibson's Neuromancer hadn't yet given us the vocabulary; Max Headroom's "20 minutes into the future" wouldn't materialize until 1985. Yet there it was: hyper-processed, digitally precise sound bleeding through analog tape hiss—the most future-facing pop music of the moment mediated through the most quotidian technology.

The mainstream American soundtrack of 1984 told a different story entirely. Van Halen's "Jump" represented about as electronic as Top 40 got, and even that was framed as a rock band making a concession to keyboards. Springsteen's Born in the U.S.A. filled stadiums with heartland rock and synthesized glockenspiel. MTV's rotation processed the aftershocks of Thriller. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a parallel sonic universe was materializing: Art of Noise dissecting pop into component samples, Frankie Goes to Hollywood turning singles into multi-movement epics, Propaganda draping Düsseldorf cool over lush digital orchestration.

For suburban listeners quarantined from post-punk, hardcore, and the ZTT/Factory Records/4AD constellation, these sounds arrived without lineage or scaffolding. No internet aggregation, no algorithmic suggestions, just fragmented media landscapes where you needed specific access points: an older sibling at college, a proselytizing record store clerk, a friend whose parents had mysteriously good taste, or sheer geographical luck. When that Art of Noise cassette appeared, it was a breach in the information quarantine—alien transmission, accept or reject.

II. The Architecture of the Invisible

ZTT Records operated less as a label than as an architectural template, a designed space into which artists stepped, were reshaped, and emerged mythologized. Founded in 1983 by Trevor Horn, Jill Sinclair, and Paul Morley, the label took its name from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's Futurist sound poem "Zang Tumb Tumb"—but this origin carries unavoidable complications.

Marinetti's 1914 poem doesn't reject war's horror; it celebrates it, attempting to sonically reproduce the Battle of Adrianople through onomatopoeia glorifying artillery and machine guns. Marinetti was a proto-fascist who praised war as "the world's only hygiene" and later supported Mussolini. This positions ZTT's naming choice somewhere between aesthetic appropriation (separating formal innovation from ideological content) and proto-edgelord provocation—using a fascist's sound poem to brand a label that would release queer anthems like 'Relax,' showcase futuristic Black innovation from Grace Jones and Africa Bambaataa, and amplify anxious German romanticism through Propaganda.

Whether Horn, Sinclair, and Morley fully reckoned with this genealogy remains unclear. The label's actual output suggests ideological distance from Futurist authoritarianism, yet uncomfortable echoes persist: the worship of the machine, the aggressive remaking of pop's traditional forms, Horn's notorious studio perfectionism and controlling contracts. The choice of "Zang Tumb Tumb" matters—even if, perhaps especially if, it was made carelessly—because it reveals ZTT's willingness to deploy maximum cultural voltage with minimum examination of consequences.

From its inception, ZTT was building across time as well as space, reaching back to early 20th-century avant-garde while constructing a pop future that wouldn't fully arrive for decades. Understanding this structure requires recognizing two distinct architects: Jill Sinclair built the foundation, and Anne Dudley shaped the acoustics (and Paul Morley painted slogans on the walls; we’ll get to him in a bit).

Sinclair: The Foundation

Jill Sinclair was ZTT's structural engineer. A former mathematics teacher who helped found Sarm Studios at 21, she built one of the most technically advanced recording environments in London—the first 24-track studio—attracting Queen, Yes, INXS, the Clash, and Madonna. By 1977, she was working full-time at Sarm. In 1978, Sarm Productions launched. When the Buggles split, she convinced her husband Trevor Horn to concentrate on production, arranging his first deals with Dollar and ABC.

In 1982, Sinclair and Horn founded Perfect Songs publishing. The following year, together with NME writer Paul Morley, they founded ZTT Records. Sinclair became managing director while Morley concentrated on marketing. That same year, they acquired Basing Street Studios from Island Records in exchange for distributing the ZTT label, renaming it Sarm West Studios.

By 1984, the Horn-Sinclair family businesses reorganized as SPZ Group: Sarm Studios, Perfect Songs, and ZTT Records. Without Sinclair's infrastructure—the physical studios, the financial architecture, the deals, the contracts—there is no ZTT aesthetic. Those rooms are the sound.

Dudley: The Resonance

Anne Dudley was ZTT's sonic architect. Classically trained with a master's degree from King's College London, she moved into session work where her professional relationship with Trevor Horn began. In 1982, she contributed to ABC's The Lexicon of Love—Horn's production that served as the pilot episode for the ZTT sound-world. She didn't just add keyboards; according to Horn, those orchestrations were her first-ever string arrangements. She reconfigured what an early-80s pop record could be, emotionally and architecturally, using strings not as tasteful garnish but as structural steel.

As a founding member of Art of Noise in 1983, Dudley helped pioneer sampling within pop music. Yet here's the productive tension: this is the same person who would later win an Oscar for The Full Monty's deeply humane score about unemployed steelworkers. The "cold" machine textures of early digital pop weren't coming from someone emotionally stunted by technology but from a composer who could write lush string lines for Seal, Pulp, Pet Shop Boys, and ABC, then turn around and sculpt a bass line that trudges like a robot on a mission.

Dudley understood how sound travels in the ZTT temple—how to make a Fairlight stab feel orchestral, how to turn a string arrangement into neon haze, how to blend stiff machine logic with emotional sweep. She shaped the acoustics of the myth.

III. "Close (To The Edit)" as Proto-Electronica Blues

Consider "Close (To The Edit)" as an early-digital, pre-electronica 12-bar blues pop construction, quietly radical for its unabashed spotlighting of the sampler. Beneath its collage surface, it obeys a cyclical call-and-response structure—machine riffs answering themselves, gated and syncopated in twelve-bar-like tension and release. The sampler becomes both bottleneck guitar and preacher's voice: elastic, defiant, endlessly re-looping.

Dudley's compositional rigor gets buried under the Trevor Horn production mythos, yet she's the one translating musique concrète into pop choreography—turning found sound into hook. The piece doesn't just feature sampling; it dramatizes it. The performer is the sampler, displacing human virtuosity with edit virtuosity.

That relentless walking bass line is concurrently unremarkable for its standard scalar structure, yet memorable and sticky probably because of it. It's the unobtrusively supportive shocks and suspension of a Casio keyboard's bass line, pumped up on growth hormones. The Fairlight sequence plods forward with that sturdy, synthetic gait—an exaggerated facsimile of a session player's "just keep it walking" brief—but inflated until it feels architectural.

Its scalar predictability gives it hypnotic neutrality, a rhythmic grid allowing everything else—sawed-off vocal samples, snare explosions, detuned orchestral stabs—to ricochet freely. Horn and Dudley understood that by making the bass part almost insultingly plain, they could frame the edits, silences, and sample punctuation as the real melodic content.

From 2025's vantage, "Close (To The Edit)" is a missing bridge between Schaeffer's sonic object and The Chemical Brothers' big-beat maximalism—musique concrète made danceable before the genre vocabulary existed. It traces its ancestry to Pierre Henry's "Psyche Rock," both works hinging on rhythm as physical artifact, an object to be manipulated rather than felt linearly. Henry's tape loops throb like proto-sequencers, while Dudley/Horn render that pulse with the Fairlight as if replaying "Psyche Rock" through chrome and glass.

IV. The Mid-80s Threshold

By 1983-84, technology had advanced enough to realize what Kraftwerk had been doing as human actors. Kraftwerk's genius lay in maintaining duality—human precision masquerading as automation, automation revealing the choreography of the human. Four men in a line, flesh pretending to be circuitry, the irony hanging like a hum in the air.

But by the time of Herbie Hancock's "Rockit" (1983), Art of Noise's "Close (To The Edit)" (1984), and Harald Faltermeyer's "Axel F" (1984), the machinery no longer needed stand-ins. Sequencers, samplers, drum machines, and MIDI protocols could finally enact what Kraftwerk had staged. The concept of "man as robot" gave way to "robot as musician." The distance between performance and production collapsed.

"Rockit" presented a near-perfect hinge between analog virtuosity and digital fetishism: Herbie's jazz chops displaced by scratching turntables, fragmented TV sets, and robot mannequins twitching in sync with the new circuitry of rhythm. It's not funk in the old sense—it's funk abstracted, automated, rendered in servo-motor gestures.

By the time "Close (To The Edit)" arrived, the novelty of the machine had hardened into aesthetic grammar. The sampler wasn't an alien presence anymore but the instrument itself, its pulse internalized. Dudley and Horn polished what Hancock and Grand Mixer D.ST. had presented as raw collision—turning mechanical stutter into compositional principle.

Then "Axel F" landed: same DNA, but stripped of irony. Faltermeyer distilled robotic funk into pure dopamine circuitry—an arpeggiated hook so clean it sounds factory-sealed. It's the European iteration of the same impulse: translating the sensuality of funk into algorithmic efficiency.

What makes that transformation poignant is how it redefined virtuosity. In Kraftwerk's hands, restraint and symmetry were acts of will. In Dudley's or Faltermeyer's, restraint became system behavior—a logic loop running until the tape ended. Yet even in that mechanized clarity, you still hear the ghost of Ralf and Florian, proving that machines could dream of being human long before humans dreamed of sounding like machines.

V. Propaganda's Lush Contrast

If Art of Noise represented ZTT's austere minimalism—the sampler as scalpel, space as weapon, silence as punctuation—Propaganda demonstrated that the same technological vocabulary could stage an opera.

Right out of the gate, "Dream Within a Dream" strikes a lushly arranged contrast to Art of Noise's sonic rationing. Where "Close (To The Edit)" uses orchestral samples like shards of glass, Propaganda melts them back into flow. The Fairlight becomes stained-glass window instead of razor blade. Arrangements feel symbiotic: synth textures blooming into strings, digital choirs blending with Claudia Brücken's voice, bass pulses that feel less sequenced than sustained.

Both groups construct from the same early-digital materials. The divide is philosophical. Art of Noise argues that the sampler is the star; Propaganda uses that same sampler to prove a new kind of romanticism is possible—one sculpted from machines but still yearning, expansive, theatrical.

VI. The Temporal Palimpsest

ZTT's history reads like science-fictional temporal stratigraphy—a label folding the spacetime of pop around itself. You peel back a layer and find Lexicon of Love DNA; another reveals Frankie's bombast; deeper still, the chrome-and-neon geometry of Art of Noise; suddenly you're in the rave years with 808 State; then surrounded by the soft bloom of Seal's voice; decades later, the reactivation of xPropaganda.

The label didn't simply evolve—it reiterated itself. Ideas recur. Aesthetics repeat. Philosophies resurface. Time loops instead of lines.

Trevor Horn's obsession with studio-as-cinema bleeds from the Buggles to ABC to Frankie to Seal without dissipating. Paul Morley's semiotic graffiti reappears in sleeve art and liner notes long after the typographical avant-garde moment should've passed. Stephen Lipson returns to work with Brücken and Freytag decades after the original collapse of Propaganda.

It's less a label than a recursive system, one that periodically reactivates its own principles in new technological contexts. A physical building ages in layers: Roman foundation, medieval walls, Renaissance facade, modern rewiring. ZTT is exactly that kind of palimpsest cathedral—every new tenant modifying the structure, every renovation revealing old stone beneath.

When you trace it from 1983 to 2025, you're not following a story of rise and fall, but a mythos that keeps reasserting itself whenever music hits a point of technological transition:

- Early sampling? ZTT.

- The art-video boom? ZTT.

- The remix as cultural form? ZTT.

- High-gloss digital romanticism? ZTT.

- The revival of synth maximalism? xPropaganda, ZTT reborn.

VII. Morley: The Slogan as Architectural Element

If Sinclair provided infrastructure and Dudley provided resonance, Paul Morley provided the conceptual packaging—the frame that told you this wasn't just pop music, but an event, a movement, a challenge. He was ZTT's chief sloganeer, and in the fragmented media landscape of the early 80s, that role was crucial.

Morley understood that you needed language as bold and immediate as the music itself. Not analysis or traditional criticism, but typographic proclamations that functioned like visual samples—fragments of meaning you could grasp instantly, even if you didn't fully understand them.

"FRANKIE SAY RELAX" "WELCOME TO THE PLEASUREDOME" "THE ART OF THE STATE"

These weren't explanations. They were memetic warfare before we had vocabulary for memes. Morley took the sampler's logic—cut, isolate, repeat, recontextualize—and applied it to language. The sleeve notes weren't meant to be read linearly so much as scanned, the eye catching phrases that functioned like hooks. Where other labels had liner notes, ZTT had manifestos.

The Marinetti connection becomes clearer here: Futurist manifestos were designed as provocations, not scholarly arguments. They used typography as weapon, language as shock. Morley imported that approach into pop, turning record sleeves into broadsheets and singles into ideological grenades. He gave ZTT its intellectual swagger, its art-school credibility, its sense that buying a 12" single meant participating in something larger than entertainment.

But "sloganeer" also implies the limits of the form. Slogans are powerful but reductive. They create mystique but can also obscure. They generate excitement but don't necessarily deepen understanding. Morley's contributions were fundamentally different from Sinclair's material construction or Dudley's compositional architecture—he was the brand philosopher, the one who told you what you were supposed to think about what you were hearing.

Propaganda and the Lyrical Dimension

This conceptual scaffolding proved particularly crucial for Propaganda. If Art of Noise was ZTT's instrumental theory (the sampler as argument), Propaganda was ZTT's emotional and narrative practice. The band's lyrics explored modern anxiety, surveillance, alienation, and Cold War paranoia—themes that resonated with Morley's intellectual framing even as they emerged from Düsseldorf rather than London.

Claudia Brücken's vocal delivery—detached, breathy, a ghostly presence suspended in vast digital cathedrals—embodied the productive tension at ZTT's core. The machine logic wasn't used to remove feeling but to frame it, making the human voice sound simultaneously fragile and eternal against the immense synthetic backdrop. Morley's slogans and manifestos created the expectation that this music meant something, that the alienation and yearning weren't just aesthetic choices but philosophical positions.

The combined effect made Propaganda the truest expression of the ZTT temple: a meticulously designed space where the romantic human voice was preserved and magnified by the very digital machinery that threatened to render it obsolete. They were performing the future, not just predicting it—and Morley's sloganeering ensured you understood the performance as statement, not just spectacle.

Yet questions linger: What happens when slogans outlive their context? When "FRANKIE SAY" becomes t-shirt cliché divorced from the music? When manifestos become nostalgia rather than provocation? Does the intellectual framework Morley built still support the music, or has it become another artifact requiring archaeological interpretation?

In 2025, listening to Propaganda means hearing through multiple layers: the music itself, Dudley's arrangements, Horn's production, Sinclair's studio spaces, and Morley's textual interventions. The slogans remain painted on the temple walls, sometimes profound, sometimes merely provocative, always impossible to ignore—even as we've forgotten what some of them originally meant to proclaim.

VIII. The Plastic Becomes Tangible

In 2025, with the proliferation of AI tools that generate complete compositions from prompts, even what felt like plastic artificiality 40 years ago now has unarguable physicality. The very thing that once felt synthetic—machine texture, quantized rhythm, edited voice—now reads as corporeal, almost handmade.

In 1984, digital instruments were prosthetics for aspiration—machines pretending to be real. In 2025, AI composition makes imitation so frictionless that human imperfection itself becomes the rare, authentic signature. The plasticity of early sampling now feels embodied because you can hear the struggle between intention and limitation, between what the machine could do and what the artist forced it to do.

The Fairlight's metallic sheen, gated reverb, rigid quantization, those specific digital artifacts of mid-80s sampling—they're no longer signifiers of "the 80s" as monolithic embarrassment. They're evidence of craft at a threshold. Dudley and Lipson working out how to make cold machinery express longing. Horn obsessing over each edit point. Claudia Brücken's voice suspended in those cavernous digital spaces, simultaneously intimate and architecturally vast.

When an AI model can generate a full orchestral cue in ten seconds, the old "artificial" becomes a site of resistance. Dudley slicing tape or programming a Fairlight wasn't automating creation; she was physically negotiating with constraints, sweating over timing and texture. The artifact—the edit click, the truncation of a loop—registers as friction, proof that there was a human pulse in the circuit.

The aesthetic valence flips: the once-synthetic now feels tactile, and the generative now feels spectral. The mechanical body has become ghostly, while we suddenly see that the ghosts of early digital music have bones.

IX. The Mausoleum That Still Resonates

Every box set is a mausoleum—six discs arriving with the somber weight of finality, everything catalogued and preserved behind glass. The music becomes artifact, the era becomes exhibit, the listening experience becomes reverent tourism through something definitively over.

And yet.

What emerges from six and a half hours with Propaganda isn't quite morbid curiosity at the tomb. It's discovering that what looked like a mausoleum from outside is actually still inhabited—that the "plastic" surfaces have warmed up, that the digital cathedrals still have acoustic life, that the machinery hasn't fully calcified into mere historical curiosity.

Some mausoleums turn out to have been designed by architects who understood resonance. The ZTT edifice—built by Sinclair's infrastructure, voiced by Dudley's arrangements, ornamented by Morley's manifestos, activated by Horn's production—was always meant to exist in multiple time zones simultaneously. Forward-looking in 1984, but also deliberately reaching back to Marinetti's Futurism, to musique concrète, to operatic drama.

The metaphor of mausoleum carries darker resonance when you consider that some artists wanted to escape before the structure was complete. ZTT's restrictive contracts—the same legal architecture that maintained the label's aesthetic coherence—trapped artists in long-term agreements that gave the label extensive control over output and image. Holly Johnson's successful legal battle to break his contract exposed the mechanism: the temple didn't just preserve and amplify; it also constrained and confined. Art of Noise and Propaganda both departed under strained circumstances, suggesting the edifice functioned differently depending on where you stood within it. For some, it was cathedral; for others, more like a very beautiful cage.

The acoustics were so carefully calibrated that when you step inside decades later, the reverb is still going, the bass line is still trudging forward with synthetic swagger, and Claudia's voice is still suspended in that impossible space between human and architectural.

The dead don't always stay buried when they were this precisely embalmed in magnetic oxide and digital samples. Sometimes they just wait for the listening technology—and the listener—to catch up to where they always were: 20 minutes into a future that keeps moving forward as you approach it.

X. Red Shift and Recursive Time

The title "Red Shift" typically describes astronomical objects moving away from us, their light stretched toward longer wavelengths as they recede. But Propaganda's red shift operates in reverse—or rather, in multiple temporal directions simultaneously.

As we move forward in time, ZTT's 1983-85 output doesn't recede into the past. Instead, it maintains a constant temporal distance: always 20 minutes ahead, always just beyond full comprehension, always about to arrive. We chase it forward through decades, and it remains perpetually contemporary, perpetually strange, perpetually almost familiar.

This is the recursive architecture Sinclair and Dudley built: a sonic temple designed to exist in multiple timeframes at once, where the "dated" becomes "specific," where "plastic" becomes "tangible," where "artificial" becomes "evidence of presence."

The temple only feels eternal because Sinclair and Dudley's work enabled it to withstand time—not by resisting change, but by encoding change into its fundamental structure. Every listening becomes an archaeological dig, every return visit reveals new layers, every technological shift makes the original construction methods more rather than less visible.

Propaganda's voice, calling from 1984, arrives in 2025 not as nostalgia but as a transmission we're only now equipped to decode. The cassette tape that arrived in suburban hands in 1984, carrying sounds from cyberspace before cyberspace existed, has become a box set—but the alienness hasn't dissipated. It's only clarified.

We're still 20 minutes behind, still catching up, still discovering that the future we're living in was already encoded in those SARM West sessions four decades ago. The red shift continues. The temple remains open. The grand priests' work echoes forward, backward, and sideways through time.

And somewhere in the machinery, in the space between Dudley's orchestrations and Sinclair's infrastructure, between the Fairlight's sampled hits and the tape's magnetic grain, the signal keeps transmitting: This is what it sounds like to live at the threshold. This is the architecture of becoming. This is 20 minutes into a future that never quite arrives.