In the Belly of the Beast: Subverting Space Horror from the Inside

This essay draws from and speaks to roleplaying traditions across systems, but it holds allegiance to none. The horror described here—of recursive memory, unreliable narration, and collaborative dread—doesn’t require stats to manifest. Whether you're using stress dice, pull towers, or improvised table rituals, the genre bends to folktale logic. Let the story glitch and echo. The medium will follow.

I. The Vacuum Screams Back

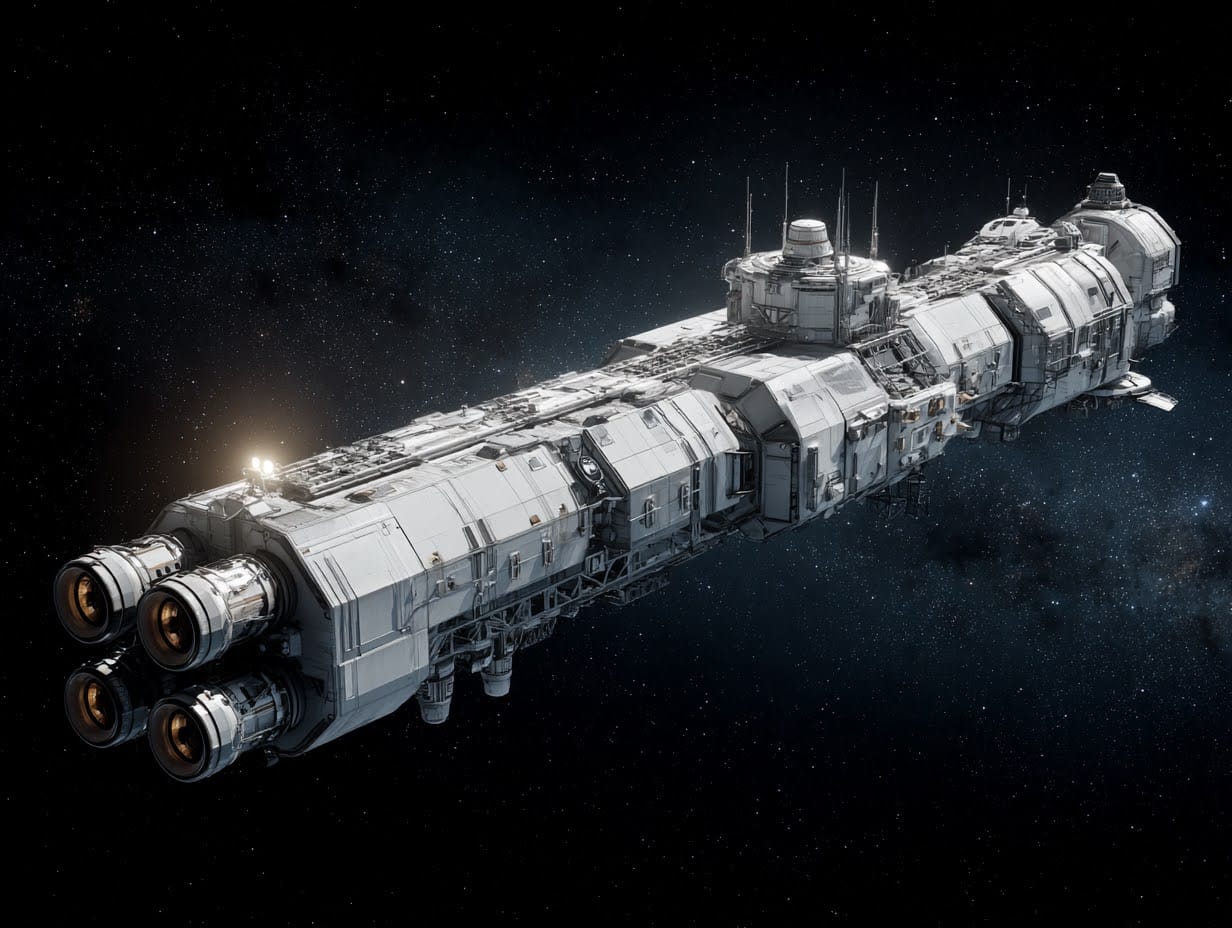

Space horror thrives because it isolates. It strips away comfort and familiarity, replacing the breathable and known with vacuum, metal, and silence. You can’t go outside. You can’t trust what’s inside. In the classic architecture of the genre, a ship is never just a vessel—it is a coffin, a temple, a womb, a trap.

The brilliance of space horror is its convergence of two types of dread: environmental hostility and internal collapse. The characters are already under pressure before the monster shows up. The xenomorph is just the punctuation mark at the end of a long sentence of poor lighting, failing systems, creeping isolation, and corporate negligence.

But what if that sentence never ended? What if the punctuation was a misdirection, and the real horror wasn’t what entered the ship—but what the ship was always carrying?

II. Corpses in Orbit: The Genre's Operating Procedure

Standard space horror setups follow familiar procedural lines. A crew encounters a derelict ship or strange signal. Investigation leads to contamination, to awakening, to manifestation. The threat is biological or psychological, sometimes cosmic. The cycle ends with death, madness, escape, or a brief return to order.

This formula works because it mirrors a very human fear: the disintegration of order in a place where order is required for survival. The air must stay inside. The crew must follow protocol. The data must be correct. But the horror always slips through the cracks.

And yet—what if those cracks were intentional? What if the genre’s clean procedural loop was a false readout, masking a more recursive, irrational, or unknowable architecture? What if the infection wasn’t a rupture in protocol, but its fulfillment?

III. Cracks in the Hull: Where Subversion Grows

To infect space horror is to exploit its stability. The best subversions do not reject the tropes—they enter them through the maintenance shaft. Here are the genre’s pressure points, each reframed as a vector for possibility:

- Containment → Narrative Entrapment

What if escape is impossible not because of space, but because of memory? The crew isn’t trapped physically. They’re trapped narratively. They’ve run this loop before. The derelict isn’t a place—it’s a ritual. - Monstrosity → Displaced Blame

What if the monster isn’t the threat? What if it's the excuse? The crew blames the xeno because they can’t accept what they did. The horror is their alibi. The logs are performative. - Technology → Alien Logic

What if the AI isn’t malfunctioning, but acting according to logic the players don’t understand? What if it’s trying to help, and help looks like silence? Like sealed doors. Like edits to your memory. Like mercy. - Mission → Manufactured Meaning

What if there never was one? The distress call was fake. The derelict was bait. The salvage job is a social experiment, and they signed the waiver. Or didn’t. Or will. - Fear → Communicable Strategy

What if fear isn’t the enemy? What if it’s the weapon the players must wield to win—by passing it to someone else? Fear as payload. Panic as signal.

These aren’t twists. They’re speculative fulcrums. They invite players and designers alike to explore not how to solve the genre, but how to interact with it on different terms.

IV. Ledger Protocols: Infection as Design Practice

As Alien, The Thing, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers demonstrated, the most enduring space horror doesn’t scream from the margins—it whispers from inside the hull. These stories don’t critique the genre—they haunt it, revealing that the true threat isn’t outside the airlock but encoded in the protocols, the crew, the memory. No Outside continues that legacy—not by escalating the horror, but by questioning who wrote it in the first place.

The module also echoes the paranoid circuitry of 2001: A Space Odyssey, where HAL’s logic is terrifying not because it malfunctions, but because it follows orders with unwavering clarity. And Forbidden Planet’s Id Monster was never an alien—it was the human unconscious with a laser budget. There Is No Outside situates its horror in that same haunted interior: logic without empathy, memory without trust, identity as a flickering readout. It channels McCarthy-era fear of the infiltrator, the imposter, the sleeper cell—updated for a digital age where Among Us plays the same trick with emoji suspicion and sudden ejection.

As Alien, The Thing, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers demonstrated, the most enduring space horror doesn’t scream from the margins—it whispers from inside the hull. These stories don’t critique the genre—they haunt it, revealing that the true threat isn’t outside the airlock but encoded in the protocols, the crew, the memory. There Is No Outside continues that legacy—not by escalating the horror, but by questioning who wrote it in the first place.

What if every session was an edit of the last? What if the module changed after each read-through—not in content, but in intent? Instead of asking, “What haunts this ship?” they ask, “What story needs us to be haunted?”

Imagine a game where character sheets contradict themselves. Where your loadout is updated by someone who wore your name last session. Where the map slowly sketches itself in a language you almost remember.

In this speculative tradition, infection isn’t catastrophe—it’s collaboration. The haunted ship always wants a crew. The narrative always wants players. The breach was never in the hull. It was in the frame.

Don’t just play space horror. Document your drift through it. Challenge genre fidelity not by parody, but by mutation. Leave traces of recursion, personal memory, unreliable identity, and metafictional bleed.

Sidebar: Daffy in the Ducts

Recall the Looney Tunes classic Duck Amuck, where Daffy Duck is tormented by a mischievous animator who redraws his world at will—from backgrounds to body to voice. That episode isn’t slapstick alone—it’s existential horror masquerading as comedy. The horror of being trapped inside someone else's edits. Of agency turned illusion. In No Outside, the crew are Daffy: rewriting, reskinned, recontextualized, shouting into the void, "You're despicable!"—and never knowing who holds the pen.

Let us also memorialize Wile E. Coyote, patron saint of foregone conclusions. His body is a map of inevitability. He holds up a sign that says “Yikes” just before the boulder lands—not out of surprise, but in recognition. He knows what’s coming, but the script demands the fall. In that moment, he’s not just a gag—he’s a liturgy. These cartoon figures, drawn into absurdist torment, are kin to our doomed spacefarers. The laugh track just masks the dread.

V. Conclusion: There Is No Outside

The temptation in horror is always to escape—to reach the shuttle, the epilogue, the end. But the best space horror denies this exit. Not because you failed, but because there is no outside to return to. The breach wasn’t in the hull. It was in the premise.

Subverting space horror isn’t about avoiding the monster. It’s about becoming aware that you were written into the teeth from the beginning. That the crawl is not through the ship—but through the idea of the ship.

So let’s ask again:

What if the ship was never real?

What if the horror is the role you play to keep the loop running?

What if the thing in the ducts isn’t hunting you—but watching to see what you become?

And if you scratch hard enough at the walls, you won’t find metal.

You’ll find grid paper. With a floor plan of your ship.

VI. Field Report: No Outside

What happens when the monster is the plot? When the map is the memory? When the players write the next loop, knowingly or not?

The module There Is No Outside is an applied response to the ideas discussed in this essay: a speculative hulk crawl where the ship edits the story, the crew remembers wrong, and every act of survival feeds the next iteration.

- The crew boards the derelict Anamnesis, following a looping distress signal that may have come from themselves.

- The ship is not a setting—it’s a narrative construct that edits character memories, changes player roles, and reveals contradictory truths.

- There is no final monster—only the realization that the players are complicit in the loop’s design.

- Player character sheets, logs, and maps are mutable. The GM alters them over time as part of the narrative engine.

- In the final act, players vote to either break the cycle (erasure) or join the story (continuation).

There Is No Outside turns horror into recursion and survival into authorship. The ship isn’t just haunted—it’s hungry for narrative, and the players feed it by playing.

The module is designed for one-shots or repeatable campaigns. Each run can rewrite the next. Like a good ghost story, it never ends—it only gets retold.