Gaps in the Feedback Loop

Memory, Relics, and the Delayed Recognition of Cultural Cornerstones

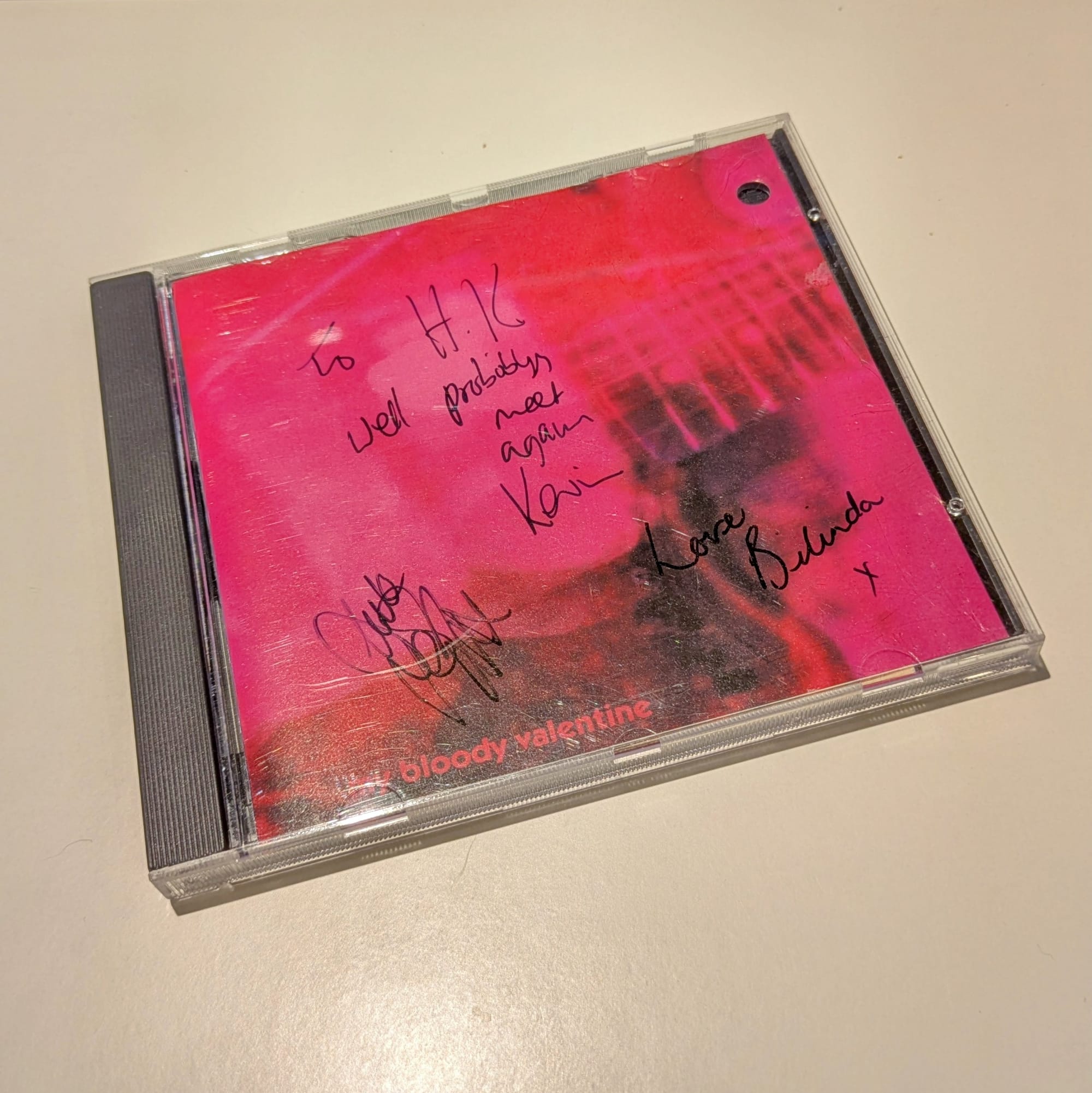

The "legendary" status of Loveless built up like a feedback loop with a bit of a delay. The UK presses were doing their usual thing of hyping things up (so they can knock it down later... a vicious, pernicious institution), and I'd gotten a preview cassette from the Sire/Warners rep... and thought it was... okay? LOL I know, heresy, right? I went to NYC in 1991 for CMJ's whatever shindig and got to say hi to Kevin whom the US label had stashed away in an upper floor of the WTC. I had the foresight to bring that advance tape and had him sign it, ergo the "We'll probably meet again" when I got to see them in Houston a few months later for the proper tour (Dinosaur Jr. was the opener).

If I recall, Loveless was far from a money maker for the label (Alan McGee would have to wait from the Brothers Gallagher for the cash printer), but it spiraled into this artistic and genre-defining monolith. Personally, the EPs around that album were the focal points of interest then, "Soon" being that irresistible lure, part raga, part sonic sculpture, and yet another Stubblefield sample that I had no clue about at the time.

And poor Clyde. If anyone recouped money, it went to the James Brown estate.

The Soft-Serve Defense

I think about how the dismissive attitudes toward Oasis were from an intellectual standpoint, which is like blaming a soft-serve cone for not being a fancy meal. Walking the dog this morning, I was thinking about my lukewarm shrug at Definitely Maybe, and eventually seeing it as less a collection of songs, but chants. Of a post-adolescent male experience, before the "respectable" day job, mortgage, and kids arrive. The "choose life" monologue from Trainspotting that is capitalism's gravitational well. Irredeemably testosterone-fueled joy, but joy nonetheless that happened to resonate with everyone else who only needed "cigarettes & alcohol" to get by.

The sibling friction, the breakup, and the unapologetic money grab of the reunion. All that feels like something right out of an Irvine Welsh tale. I don't think the Gallagher bros (and "bros" in the truest sense) need any form of public rehabilitation; they've gotten their filthy lucre and that's plenty. And even this peering through the rear view mirror, where objects are closer than they appear, is recognizing what objects, people, and events are now, in addition to how one remembers them then.

Cultural Fulcrums and the Economics of Artistic Vision

I'm going to sound like Jan Brady complaining about Marsha, but going "Recuperation! Recuperation! Recuperation!" One could assume that Alan McGee was signing bands that he thought were resonant with the times, not necessarily as money makers, but something that rang with him at the moment. A person with influence and some degree of resources could and did act as a cultural fulcrum. And eventually Sony absorbed the discography like an amoebic pseudopod.

Daniel Miller once said that it's Depeche Mode that funds Diamanda Galas on his label. And Ivo Watts-Russell had Pixies and Breeders bankrolling Lisa Germano and Kendra Smith. While Tony Wilson just plain lost money.

These label heads understood something fundamental about cultural influence: you need your accessible hits to subsidize your uncompromising artists. Miller's Mute, McGee's Creation, Ivo's 4AD—they all operated on this delicate ecosystem where commercial success creates space for artistic risk. Wilson's Factory Records proved the inverse: that pure artistic vision without financial pragmatism leads to beautiful bankruptcy, legendary clubs that lose money every night, and cultural influence that outlasts the bank account.

Relics of Secular Faith

I'm sure I still have the advance tape and the CMJ badge somewhere. I still have the "Soon" t-shirt I bought at the Houston show, well-worn with at least one hole somewhere, and I'm sure that's worth some cash to someone. Speaking of holes, I think about the promo punch out on that copy of Loveless, how record label lagniappe can end up as currency that appreciates in value on illogical and incomprehensible scales.

Relics of secular faith are real and go for real money. The promo punch-hole that was meant to mark something as worthless promotional material becomes exactly what makes it precious to collectors decades later. That "Soon" t-shirt gains value from its holes—wear and tear that proves authenticity, that someone was actually there, actually lived with the music rather than just accumulating it. The advance tape with Kevin's signature sits somewhere in a box, a piece of music industry archaeology likely worth more now than when it mattered to anyone's quarterly projections.

However, my reliquary is largely of the mind, revisited while waiting for the pooch to finish sniffing and to do her business.

The Feedback Loop of Recognition

There's something beautiful about cultural objects that require time to reveal their importance. Loveless needed that delayed feedback loop to become legendary—the initial lukewarm reception, the gradual critical reevaluation, the influence spreading through subsequent generations of musicians who heard something the original audiences missed. Oasis needed decades of distance before anyone could admit that those chants served their purpose perfectly, that soft-serve ice cream has its place in the cultural diet.

Memory plays its own tricks with these artifacts. The objects in our rear view mirror are simultaneously closer and more distant than they appear. That signed advance tape contains both the memory of meeting Kevin Shields in a tower since destroyed and the knowledge of what Loveless would eventually become. The CMJ badge represents both the hustle of early '90s music industry networking and the quaint notion that physical gatherings could determine cultural trajectories.

We carry these relics—physical and mental—not because they predicted the future, but because they preserve moments when the future was still unwritten. When an advance cassette could be just another okay album from the label rep, before feedback loops and critical consensus transformed it into something monolithic. When signing that tape was just a polite interaction with a musician, not the documentation of cultural history.

The real feedback loop isn't just about how albums gain legendary status—it's about how we, the witnesses and participants, slowly understand our own roles in these stories. Sometimes you're just walking the dog, letting your mind wander, when you realize you've been carrying around pieces of musical history all along, most of it stored not in boxes but in the space between memory and recognition, where objects become more and less than what they seemed at the time.