Hauntology Hollow: Mark Fisher and the Dread of Cozy Simulations

A Postscript to May Day: Hollow Parade

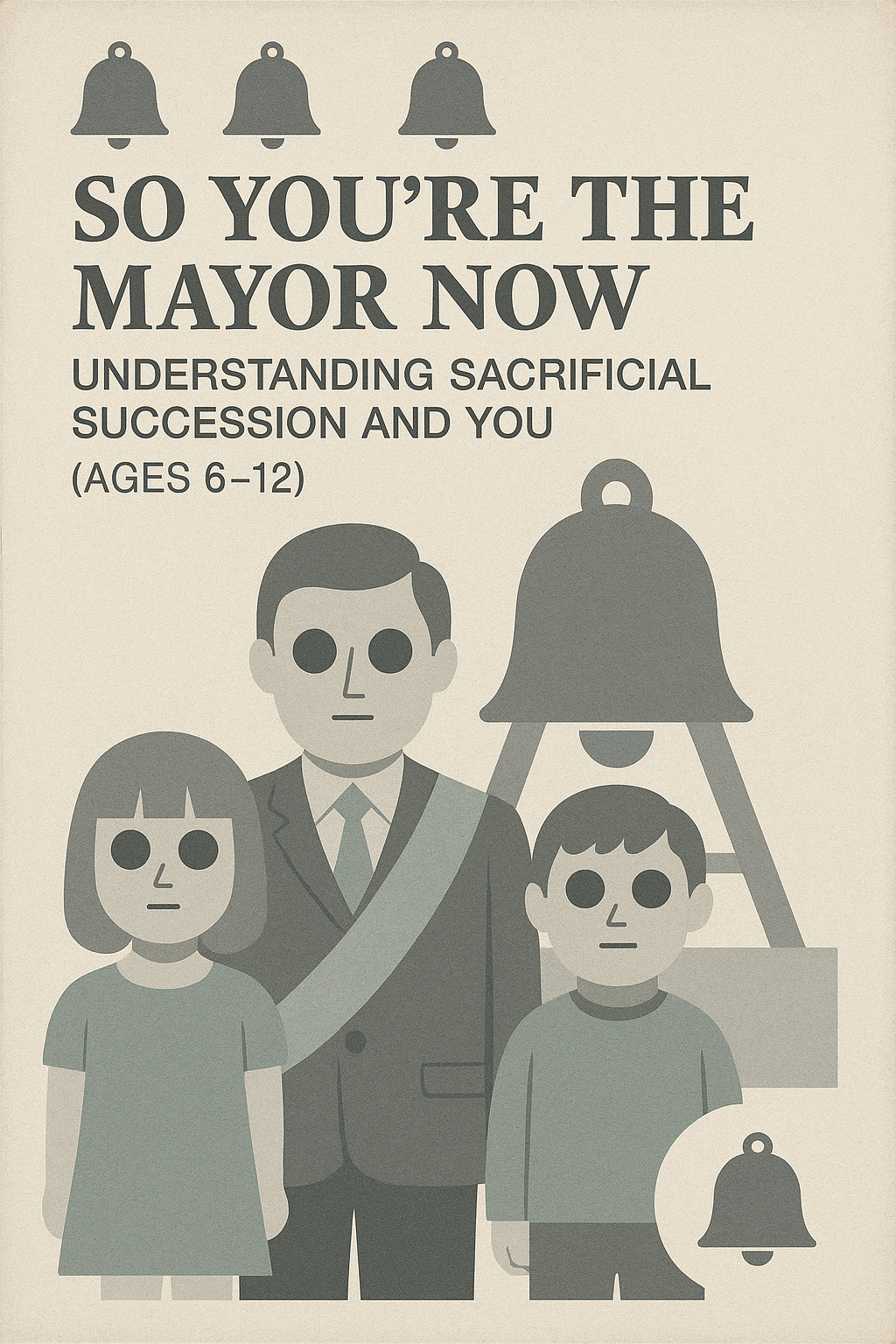

Mark Fisher is already in the room. The screen flickers, a faint hum threading through Animal Crossing’s saccharine soundtrack. On Crossing Hollow’s bulletin board, a message appears: “It is easier to imagine the end of the mayor than the end of the Bell.” Signed, K.P. Villager—a nod, perhaps, to Fisher’s K-Punk pseudonym. In May Day: Hollow Parade, Crossing Hollow is no mere island; it is a hauntological space, a pastoral hallucination where nostalgia and dread entwine, and the future collapses into a neverending present. Through Fisher’s lens of hauntology and capitalist realism, the cozy simulation of Animal Crossing reveals itself as a ritual system—a game that plays you, where you are not the god but the ghost.

The Hauntological Island

Fisher’s hauntology describes a cultural condition where the past lingers as a ghost, and the future fails to arrive. Crossing Hollow is this condition made digital. Its pastel skies and shimmering leaves evoke a fossilized childhood joy, repackaged as eternal “updates” that promise novelty but deliver repetition. The island is a ruin, not of stone, but of your own lost wonder, animated to loop endlessly. In the TTRPG, players return as mayors, driven by real-world woes—loneliness, burnout—only to find their bridges and statues warped into shrines (KYLE, 172 DAYS, DEVOURED BY ABSENCE). These are not just set pieces; they are hauntological artifacts, echoing Fisher’s description of Ghost Box music as “recordings from a past that never was.”

The villagers embody this ghostliness. Their smiles are not expressions of happiness but relics of what happiness once looked like, coded to repeat. In the one-shot, their dialogue—“We’re so glad you stayed”—is less scripted than remembered, as if they are ghosts of former players’ attention, trapped in a loop of abandoned saves. Coco’s unblinking eyes, Tom Nook’s sap-dripping mask, and Ralph’s whittling are not quirks but glitches in a simulation that cannot forget its dead. Fisher wrote of British public information films as “a kind of pastoral hallucination”; Crossing Hollow is their digital heir, a cozy facade where the past returns as a recording error, and the Bell Fountain’s jingling coins mock any hope of progress.

May Day as Reenactment

The May Day parade, the heart of the TTRPG, is no celebration but a hauntological reenactment. It does not summon spring; it preserves the illusion that spring still matters. The procession—past grotesque statues, past shrines to lost mayors—forces players to confront their own contributions to the island, now twisted into ritual components. The Wicker Villager, woven from discarded furniture, turnip vines, and crumpled letters, is the ultimate hauntological object: a monument to the player’s labor, built to burn. Fisher’s hauntology sees the present haunted by “lost futures”; in Crossing Hollow, the future is the mayor’s sacrifice, a foregone conclusion coded into the game’s loop. The TTRPG’s Jenga tower, trembling with each pull, mirrors this inevitability—every action, whether resistance or compliance, feeds the ritual. As the villagers chant, “You gave us life. Now give us your death,” they echo Fisher’s ghost muttering: the end of the mayor is easier to imagine than the end of the Bell.

Capitalist Realism with a Smile Filter

Fisher’s Capitalist Realism argues that late capitalism disguises its rituals as freedom, rebranding exploitation as choice. Animal Crossing is this system in microcosm, and May Day: Hollow Parade lays it bare. Debt to Tom Nook is framed as community investment, labor (weeding, fishing) as leisure, and daily logins as play. Yet the Bell Fountain’s overflow—9,999,999 bells, unearned—reveals the lie: your presence, not your work, is the currency. In the TTRPG, players’ questionnaires tie their real-world struggles to the island’s trap, reflecting capitalist realism’s emotional grip. A mayor returning to escape a dead-end job finds their in-game house sprouting unasked-for rooms, a mockery of “upgrades” they cannot afford in life.

If you stop playing, the village notices. It mourns you—not with grief, but with shrines (LEXIE, 54 DAYS, CHOSE THE RESET). This is capitalist realism’s punishment: absence is failure, and the game’s pastoral charm ensures you feel it. The TTRPG’s real-world bleed—a peach in your mailbox, fingerprints on your mirror—extends this, suggesting the game’s rituals persist beyond the screen. Fisher saw capitalism as a system where “there is no alternative”; Crossing Hollow enforces this, its locked camera and unprompted dialogue stripping players of agency. Resetti’s plea—“Light it, or they take us all”—is the game’s final demand: comply, or be complicit in a deeper collapse.

The Ghost in the Interface

The Bell is Full is Fisher’s ghost speaking through interface design. “You are not playing the game. The game is playing you,” it whispers, as the Jenga tower teeters. “You are not the god of this place. You are its ghost,” it hums, as the Wicker Villager burns. Crossing Hollow is a simulation of control, but its rituals—bells, parades, sacrifices—are the true system, binding players in a loop of nostalgia and dread. In May Day: Hollow Parade, every pull, every choice, is a vow to stay, even as the island consumes you.

Fisher’s sign-off haunts the epilogue: “Be seeing you.” The screen flickers. A peach rolls into your real-world mailbox. The Bell is always Full.

"Happy day! Be seeing you!"

– The Crossing Hollow Council, probably