Gundam as Military Child Labor Horror

How a Franchise Built on Anti-War Trauma Became a Celebration of the Very War Machine It Condemned

I. The Tomino Contradiction

Yoshiyuki Tomino didn’t want you to love war. He wanted you to fear it.

The original Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) wasn’t a power fantasy. It was a bleak space opera about teenagers being conscripted into war by desperate adults. The protagonist, Amuro Ray, doesn’t dream of being a hero. He becomes one out of sheer survival instinct, pushed into the cockpit of the RX-78 because everyone else is dead or dying.

Tomino has said, repeatedly, that he hates how fans glorify the violence. In post-Zeta Gundam interviews, he expressed regret that the anti-war message was lost amidst the explosion animations and model sales. In a 1986 interview with Animec magazine, he lamented that fans fixated on the "cool" mobile suits while ignoring the human cost. He called Newtypes "evolved tragic figures" and criticized the fandom for missing the point. Depression haunted his creative choices.

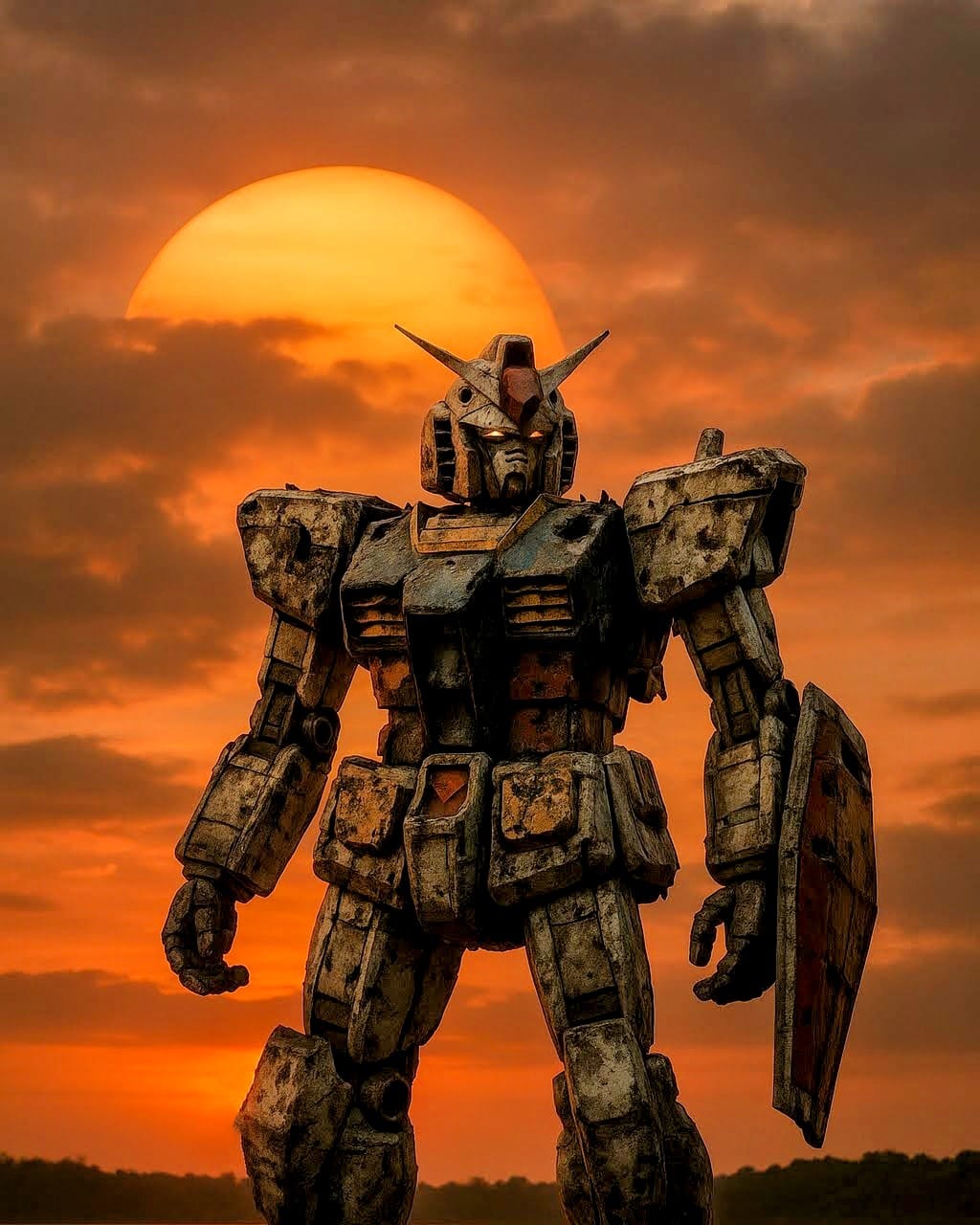

He saw Gundam as a warning about militarism, born from his own experience growing up in post-war Japan, where the shadow of World War II and the specter of nuclear annihilation loomed large. The RX-78-2 wasn’t a superhero’s chariot; it was a desperate prototype—a symbol of humanity’s failure to avoid war.

Yet here we are—40+ years later, surrounded by racks of Gunpla kits, energy drink collabs, and pop culture articles celebrating Gundam as a shining icon of anime cool.

This isn’t just fandom misreading. It’s capitalism doing what it always does: defanging resistance, selling it back with better articulation and glow-in-the-dark accessories. Anime itself—visually lush and serialized—often amplifies what it seeks to critique. The same explosion that kills a pilot is animated with such care it becomes aspirational. Apocalypse Now warned of napalm; pop culture made it a T-shirt. Gundam did the same with beam sabers.

II. The Newtype Horror

Newtypes are often misinterpreted as anime Jedi: humans who "awaken" to better piloting skills through mysterious psychic upgrades. But their abilities aren’t gifts. They’re symptoms of exposure to war.

Newtypes are trauma-empathic weapons.

Every Gundam protagonist becomes a Newtype not because they trained or deserved it, but because they suffered. Because they watched friends die. Because they killed too many people to remain untouched.

The arc is always the same:

- Learn empathy through combat trauma

- Connect with the enemy

- Become overwhelmed by the scale of suffering

- Die, disappear, or lose humanity

This is not a hero's journey. This is a psychological horror story. And the mecha—those towering mobile suits with beam sabers and bladed shields—are coffins with power buttons.

Tomino’s 1999 Newtype interview made it explicit: Newtypes were meant to warn us what happens when humanity pushes too far into conflict. Amuro sensing Lalah's death in MSG, Kamille’s mind fracturing at the end of Zeta—these aren't character climaxes. They're system failures.

Newtypes are closer to the tortured psychics of Scanners or Akira than to Luke Skywalker. They aren’t chosen. They’re broken open.

III. The Gunpla Capitalism

Let’s not pretend: Gundam survived because of plastic.

Model kits (Gunpla) saved the franchise from cancellation. The real robot boom didn't just sell realism—it sold hardware. War machines rendered in perfect 1/144 scale. Kids could reenact space battles in their bedrooms, placing Zaku limbs where their toy soldiers once lay.

But what exactly were they reenacting?

When Bandai sells a high-end model of a prototype weapon that killed its test pilot in episode 12, that’s not neutral merch. That’s commemorative trauma. Every limited-edition colorway is another nail in Tomino’s philosophical coffin.

The message was supposed to be: don’t build these machines.

Instead, it became: build them better, and pre-order before they sell out.

Gunpla’s success isn’t incidental—it’s astronomical. By 2023, Bandai Namco reported over 500 million Gunpla units sold. That’s not just business. That’s cultural transformation. The act of building these kits is meditative, even empowering—but it’s detached from the narrative. You’re assembling a weapon that, in-universe, slaughtered thousands. It’s like selling luxury model guillotines from the French Revolution.

And Gunpla is just the beginning. Gundam Wing’s Toonami-era edits downplayed the politics. Video games like Battle Assault or Gundam Versus let players revel in carnage without consequence. The franchise’s anti-war message was drowned beneath the sound of plastic sprues and console clicks.

IV. The Pipeline: From Trauma to Toy

Here is the pipeline of military-entertainment ideology:

- Watch Amuro cry in the cockpit

- Feel his pain, his fear, his dread

- See the RX-78-2 rise like a god

- Want it

- Buy it

- Forget the pain

This is not incidental. It’s intentional.

Modern marketing doesn't separate meaning from merchandise. It fuses them. Gundam's anti-war narrative became the delivery mechanism for pro-war aesthetics. A 14-year-old sees a child soldier break down under pressure... and then begs for a perfect-grade kit of his suffering.

This isn't limited to Gundam. Call of Duty. Transformers. Paw Patrol. They all operate on the same axis: militarized iconography embedded in play, normalized through repetition, sold as empowerment.

What makes Gundam especially insidious is its self-awareness. The franchise built its own critique into the text. Char’s nihilism. Zeon’s moral ambiguity. Amuro’s breakdowns. And still—the marketing machine sold it as sleek and aspirational.

Recent fan posts capture the disconnect perfectly: “Just finished my MG Barbatos. This thing’s a beast!” No mention of Iron-Blooded Orphans’ child soldiers or mass graves.

Because play feels good. Because the RX-78 is beautiful. Because the message is easier to forget than the color scheme.

V. The Final Detonation

Fans will say:

- *"Amuro is a hero!"

- *"Stop overthinking it!"

- *"Let people enjoy things!"

But if your enjoyment requires you to ignore a franchise's core trauma, maybe you were never its intended audience.

Tomino didn’t want pilots. He wanted witnesses.

"If you can't admit Gundam is about child soldiers, maybe you're the one who's been brainwashed by the Earth Federation."

The mecha genre isn't power fantasy. It's power fatalism. The machine wins. The pilot screams.

VI. From Witnesses to Resistance?

The tragedy of Gundam is not just its misreading—it’s its co-optation. But not all fans miss the point. Subcultures exist around War in the Pocket, 08th MS Team, Thunderbolt—stories that center grunts, medics, and ghosts. Fans still post about Kamille’s psychic collapse or the terror of Zeta’s final arc.

These are the witnesses Tomino wanted.

But they are often drowned out by louder fandoms: the ones who cheer for the perfect head sculpt, who skip the dialogue for the next beam saber clash. These voices don’t need silencing—they need reminding.

Susan Sontag once wrote that images of suffering can desensitize as much as they can awaken. Gundam’s beauty risks hiding its pain. But every model kit, every rewatch, every mission replay is a chance to see it again—not as a celebration, but as a warning.

We can enjoy the builds. But we must never forget what they were meant to represent.

Individual heroics are temporary. One Year Wars are permanent.