Following the Thread (Backwards)

It started innocently enough, the way these things often do: Slayer's Seasons in the Abyss, put on after a long absence, and a technical question that hadn’t mattered the first time around. How clean the separation was between rhythm and lead. How intentional the overdubs seemed. And then, inevitably: where the hell did the bass go?

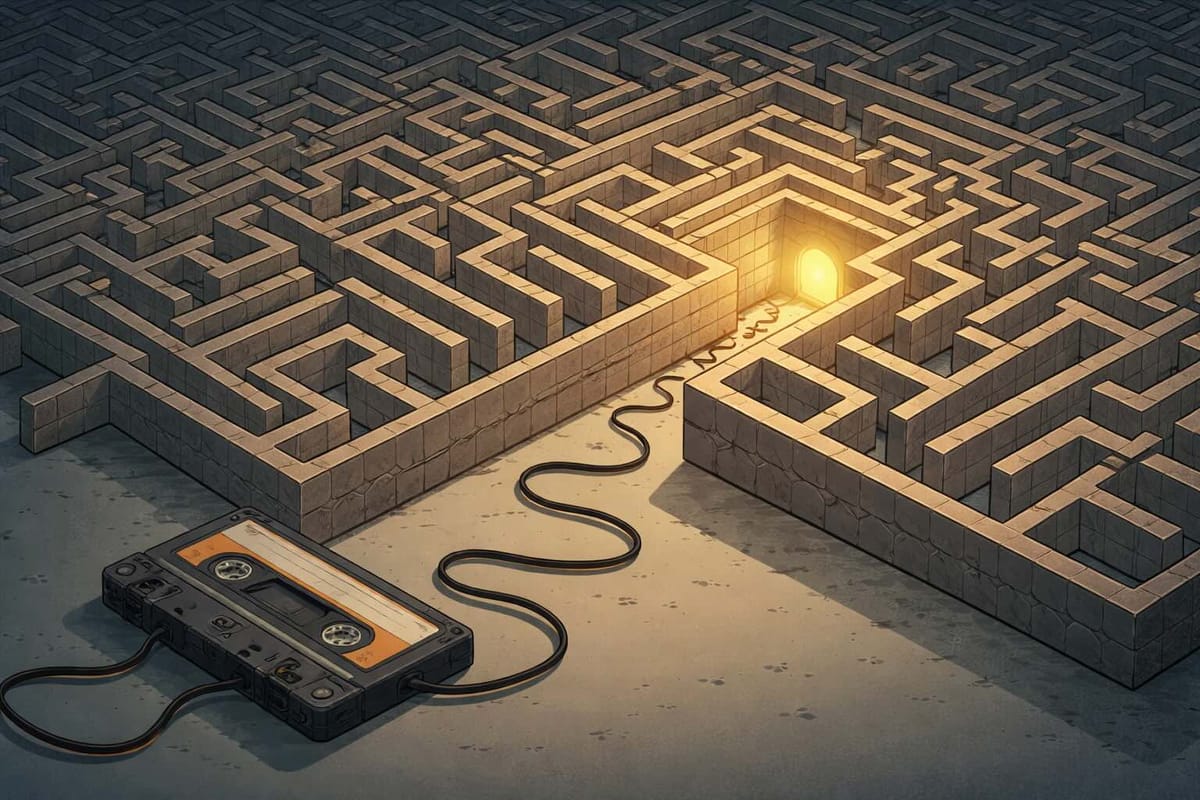

That kind of noticing is dangerous. Not because it’s wrong, but because it opens a door you didn’t intend to walk through. Once you hear absence as a choice rather than a flaw, you start listening for decisions. Once you start listening for decisions, the record stops being only a delivery system and starts becoming an object. The engine is still running, but now you can see the pistons and the missing catalytic converter.

This is not nostalgia. Nostalgia wants the past to return intact, glowing, morally uncomplicated. This is something colder and, oddly, more generous. An audit of affect. What does this actually do to me now, absent the old stakes?

The answer, it turns out, is: different things, depending on the material.

Some records still function exactly as designed. Not “important,” not “redeemable,” not even admirable — just effective. A few years ago I walked into a gun shop and heard Marilyn Manson's Holy Wood playing over bad speakers under fluorescent lights. Horrid human being. Compromised work at best. But still rocks. The mechanism engaged immediately, not for me, but for the room. The weapon wasn’t spent. I’d just stopped being the target demographic.

That distinction matters. “Selectively live” separates this from both the nostalgist fantasy (“music used to be dangerous”) and the dismissive one (“I’ve outgrown this”). Neither is honest. The mechanism is intact. The calibration is legible. My position relative to the barrel has changed.

Other records reveal something else under scrutiny. Dimmu Borgir's mid 2000's symphonic indulgence, once overwhelming and tailor-made for Hellboy trailers, now reads as theatrical staging — spacious mixes built to let orchestras breathe, spectacle doing legibility’s work. Entombed's Wolverine Blues by contrast, still hits physically. The bass is present, grinding like an outboard motor under the hull, and suddenly the inheritance from hard rock and punk becomes obvious. Different delivery systems solving the same problem: how to produce impact.

And then the thread keeps pulling.

From thrash to orchestration to groove, and suddenly you’re listening to documentation of Hermann Nitsch's Actionist processions — Gregorian chant rolling out of the speakers plus an actual honest-to-Guderian tank (yes, my inner WWII historian is trying to show off) rumbling past the living room. Here the spectacle stops pretending to be incidental. The ritual is the work. But the document enters your space without obligating you to enter the ritual. You can hear the scale, the absurdity, the historical weight, without enlisting.

At this point it would be easy to mistake the essay for a story about escalation: heavier, stranger, more extreme. But that’s not actually what’s happening. To test the method, you need a control sample.

Enter Buzzcocks.

No spectacle. No theory. No grand posture. Just sardonic observations about ordinary emotional failures, wrapped in fuzzy three-chord austerity that somehow never feels stingy. Two guitars, a muscular bass doing real labor, drums that move things forward, and Pete Shelley singing like someone thinking out loud rather than performing an identity.

This is the control condition because the mechanism was never built as a weapon. It doesn’t recruit. It doesn’t harden. It doesn’t overwhelm. It works like a tool — reliable, repeatable, humane. The compression is generous. The songs are short, but nothing feels withheld. They don’t age into spectacle because they were never calibrated for domination or myth.

And that explains, maybe, why they’ve never quite occupied the same American canonical tier as bands with cleaner narratives. They weren’t oblique enough, angry enough, tragic enough, political enough, scandalous enough. They didn’t signify anything beyond themselves. They wrote perfect songs about wanting things you couldn’t have and being disappointed by things you got. That’s harder to monetize as meaning.

Placed next to the weaponized records, Buzzcocks don’t feel diminished. They feel stable. They prove the method isn’t about demystifying the past or congratulating oneself for survival. It’s about watching what different machines were designed to do — and noticing which ones still function without needing a firing context.

The domestic context matters more than any of the theory. This listening doesn’t happen in isolation. It happens our home where my spouse's curatorial gravity is always present — Finnish folk, freeform radio, shared jokes that keep the whole thing from hardening into self-seriousness. A well-timed eye roll and a “Boys,” is an instant peer review of sonic testosterone therapy. “Moo. Moo. Moo.” to deflate Nitsch's bovine-butchering spectacle is continuity of practice.

The 1989 version of this observation would’ve been advocacy: Here’s why this matters. Here’s why you should care. Zines were engines then — recruitment, scene maintenance, belief propagation.

The 2026 version doesn’t do that work anymore. It doesn’t need to. This isn’t memoir, exactly, because the self isn’t the subject. It’s closer to auto-ethnography, treating one listener’s responses as data rather than destiny. Watching where things still work, how they work, and who they work on.

Here is a thing that once functioned as a weapon. Watch what it does now.

Sometimes it still fires. Sometimes it reveals its construction. Sometimes it becomes theater. Sometimes it becomes ritual. Sometimes it just keeps doing its job quietly, decade after decade, like a good tool waiting in the drawer.

The thread doesn’t lead to a conclusion. It leads back through accumulated layers, through rooms and systems and jokes and bodies that have changed. The charge is still there, selectively. The machine still runs. You don’t have to climb aboard to hear it pass.

You just follow the thread. Backwards.