Feed Me Weird Things: A Quarter Century Later

The First Time I Heard It

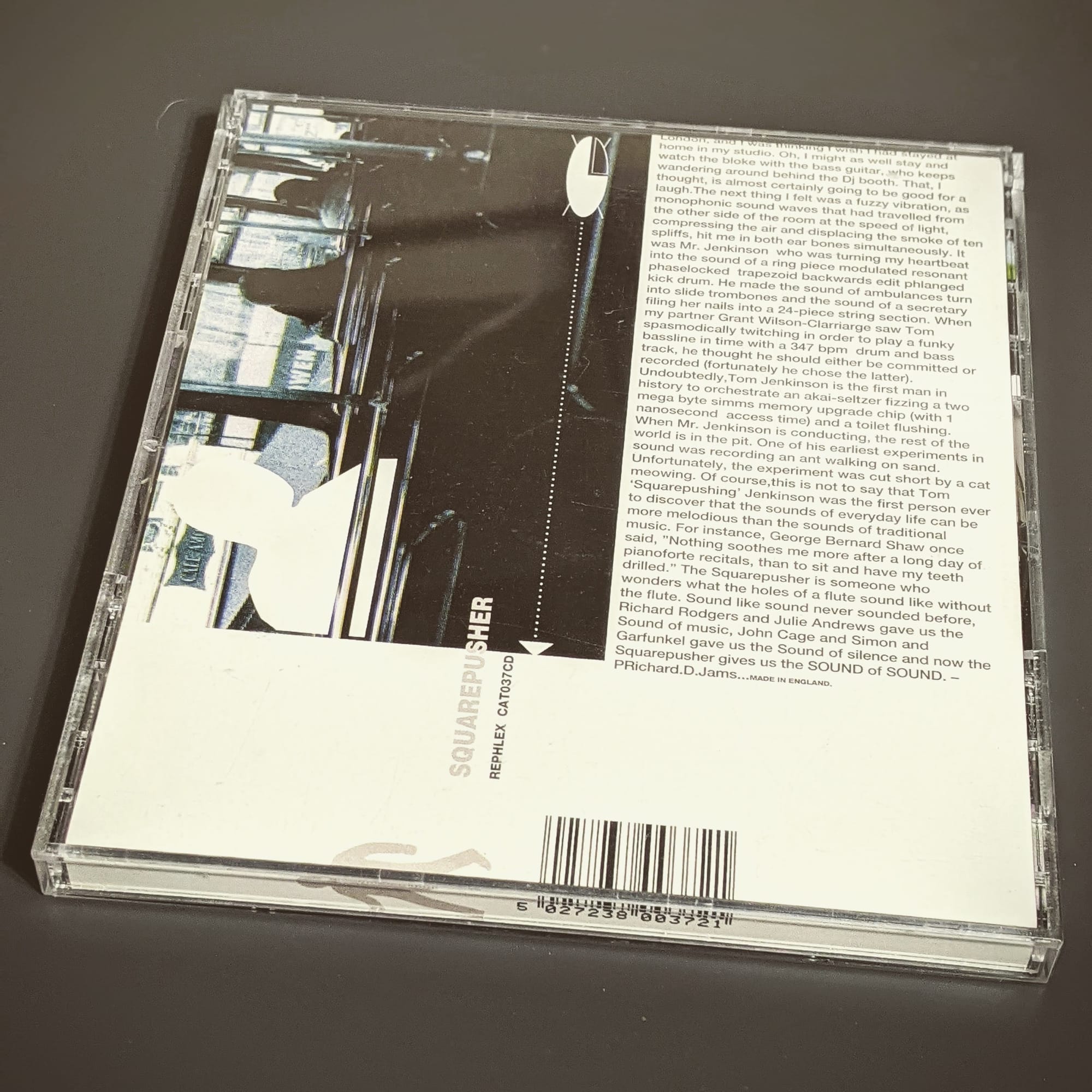

Feed Me Weird Things, the debut long-player from Squarepusher, née Tom Jenkinson, recently celebrated its quarter century anniversary, marked by a remastered reissue on Warp Records. Pictured here is the original 1996 edition, courtesy of Richard D. James's Rephlex label. In addition to playing Squarepusher's patron for this album, the Aphex man himself provided liner notes as manically dense and whimsical as the contents therewithin.

I was introduced to Jenkinson's signature blend of fractured breakbeats—or broken beats—and virtuoso electric bass at an earlier location of Aquarius Records in San Francisco when proprietor Windy Chien popped on the "Port Rhombus" single and left me with a severe case of delighted WTFBBQ. We heard of a full-length in the works sometime thereafter, and this being the mid-1990s it required some looking high and low to acquire a copy of this rather pricey import CD that took its sweet time making its way to a record rack in Houston. I opted for the digital download of the reissue, so I can't comment as to whether the 2021 edition retains the crit-inflicting wall of text masquerading as line notes, but I would assume it does.

The Scene That Spawned It

In my mind the triumvirate of Richard D. James, Tom Jenkinson, and Mike Paradinas (the latter better known as Mu-Ziq, Luke Vibert, etc.) was responsible for creating a shard-laden, manically surreal electronic music that could not have come from anywhere or anywhen else than pre-millennium Britain. This was music born from a perfect storm of cultural, social, and economic factors: post-rave comedown culture, cheap sampling technology becoming accessible, the dole providing just enough safety net for musical experimentation, and pirate radio creating underground networks. It didn't reject the dancefloor so much as pave it over with a turbo-charged steamroller and put up a carpark designed by Escher, nor did it eschew grooves but adopt its own eyes-rolled-back, inward-fixated, bordering-on-a-seizure wobble.

That spark of converging factors gave us jungle, trip-hop, drum'n'bass, and IDM—though "intelligent" still makes my wife and me cackle; we ask what its antithesis would be: "ass-dumb"? The pretension of that label perfectly captures the '90s need to legitimize everything through academic-sounding categories, as if other electronic music was somehow "unintelligent."

Tracks like "Squarepusher Theme" felt like a jet engine trying to beatbox over a skipping jazz record—jittery, exuberant, borderline absurd. It wasn't just genre-defying; it was gravity-defying. The bass lines moved with liquid complexity while the beats splintered into algorithmic fragments, creating music that sounded simultaneously hyperkinetic and deeply musical.

Between 1998 and 2001, we visited London relatively frequently, experiencing this music in its native habitat through the record shops of Soho, Covent Garden, and Notting Hill Gate. It was a remarkable and unrepeatable experience of witnessing music happen in real time—walking into Rough Trade or Sister Ray and finding genuinely unprecedented sounds that had been pressed the week before. Geography mattered then in a way that seems almost quaint now when digital distribution flattens everything.

On Privilege and Perspective

Looking back from 2025, though, I'm aware of privilege dynamics that weren't on my radar then. What felt like genuine cultural immersion—tracking down records, experiencing "authentic" underground scenes—was indeed a form of cultural tourism enabled by having the resources to travel repeatedly to London and buy expensive imports. The artists creating this music were often doing so from necessity as much as passion, making art from economic precarity while I could engage with it as aesthetic adventure, collect it as cultural artifact, then return to Texas. That's a fundamentally different relationship to the music and the conditions that created it.

This awareness doesn't invalidate the genuine excitement of discovery or diminish the music's innovations, but it does reframe the experience. That moment was "unrepeatable" not just because the cultural and technological conditions changed, but because our understanding of what those cross-cultural expeditions actually meant has evolved significantly.

Revisiting the Artifact

I suspect that Squarepusher and this particular album introduced more people in the mid-'90s to the fretless magus Jaco Pastorius than a Goodwill milk crate of Weather Report LPs. Oh, and that George Bernard Shaw quote in the liner notes is legit. I could Google to confirm whether that is the origin of the pigeonhole "drill'n'bass," but I'll assume that it is.

The music endures, complex and thrilling as ever, even as we've grown more aware of the contexts that shaped both its creation and our consumption of it. Sometimes the most honest response to our past enthusiasms is neither pure nostalgia nor complete repudiation, but recognition of both the genuine artistic excitement and the blind spots that accompanied it.

And even now, more than a quarter century later, when those broken beats kick in, some part of me still wobbles across that Escher carpark, wide-eyed and weightless.