Electric Eden Meets The Lost Folk

Well, what have we here?

We made a joke, of course.

That's what Electric Eden was — and still is — a sharpened stick whittled into a kind of prank, poking at the ambered reliquary of British folk tradition. We wrote a rules-light machine for breaking songs because we wanted to point out that the songs were already broken — and that the act of "preserving" them often meant flattening their edges and polishing away their teeth. We wrapped the whole thing in gleeful meta-commentary about NPCs with bunions and temporal interlopers who think they're fixing things while mostly just making new messes.

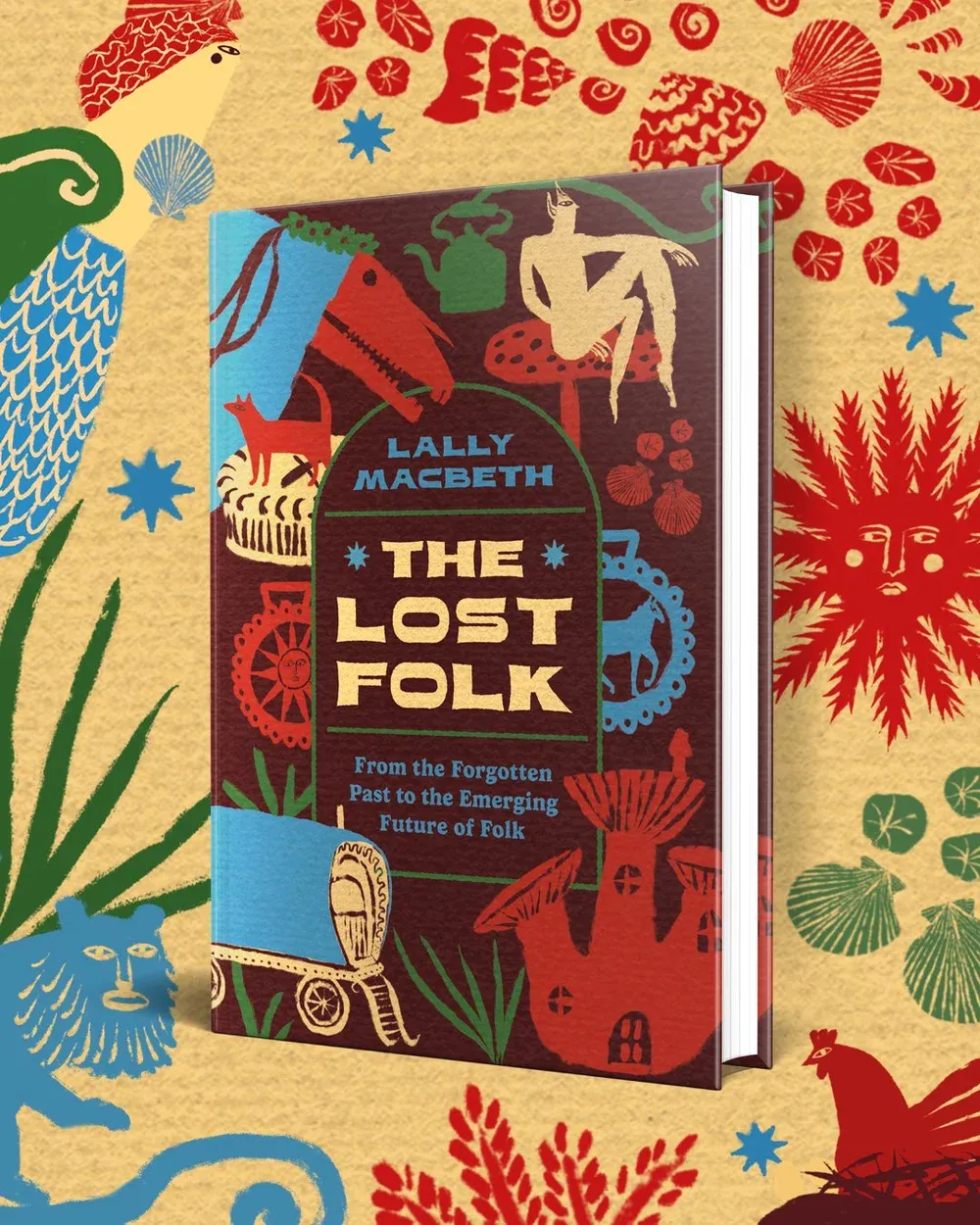

Then, just after we'd loosed that joke into the world, along came Lally MacBeth with The Lost Folk, and suddenly the joke wasn't a joke anymore — or rather, it was, but now it had company.

Parallel Inventions

What's eerie about reading The Lost Folk after Electric Eden is how much common ground there is beneath two very different surfaces. MacBeth is serious where we are satirical, tactile where we are abstract. She is out there in the field, camera in hand, kneeling in the grass or flipping through box files in some forgotten county archive, trying to map the living edges of a thing that refuses to sit still.

And yet:

Her insistence that folk is mutable — "just as you think you have a grip on it, it slips" — could be a line lifted straight from our Wayback Protocol notes.

Her fury at the gatekeepers, those who "collect" and curate as though they own the song, hums with the same charge that birthed our Folknet, that absurd and not-absurd AI enforcer of canon.

Her reverence for the overlooked — for the women, the outliers, the eccentrics with sheds full of magic — mirrors our quiet hope that in the chaos of our joke, someone might hear the voices that had been written out.

It's less a coincidence than a convergence. The cultural air is thick with this idea: that tradition is not a museum piece but an unruly commons, a perpetual negotiation between memory and invention.

What MacBeth Saw That We Missed

If Electric Eden erred on the side of detachment, The Lost Folk invites us to close that gap. MacBeth's book is full of names, of stories, of small, fragile particulars: a tinted photograph of a great-great-aunt in Tudor dress; a forgotten model village crumbling under coastal rains; Barbara Jones arguing that beer labels are as worthy of preservation as tapestries.

She writes with a deep sense of care. Her collectors aren't just archival abstractions but people with lives, losses, and labor. Mary Neal teaching working girls to dance. Lois Blake reconstructing Welsh steps from memory. Elsie Matley Moore painting stained glass while bombs fell. Reading these accounts, you realize how many ghosts we left unacknowledged in our game's sly laughter.

Our bunion jokes land differently when you've just read about someone walking miles of hedgerows, notebook in hand, because they couldn't bear to let a song slip away.

The Earnest and the Electric

What MacBeth does in The Lost Folk is something we didn't — and maybe couldn't — attempt in a game format. She grieves. Not just for the lost songs but for the lost collectors, the forgotten archives, the municipal customs dying of budget cuts and bureaucratic neglect. She understands that every erasure is a small violence, that the absent harmony haunts the surviving melody.

By contrast, Electric Eden keeps its distance. Our satire collapses the tension of preservation into a kind of joyful chaos, where every intervention spawns a variant and no version can ever truly be "the one." That distance has its uses — irony is a safehouse — but MacBeth reminds us what's at stake when you step outside it.

Where the Joke Grows Teeth

And yet — this is the trick — her book sharpens our joke rather than dulling it. Because what The Lost Folk makes plain is that the amber we were poking at was never truly static. The canon has always been contested ground, shaped as much by improvisation, chance, and power as by any single hand.

MacBeth writes about collectors and curators as people, flawed and human, but also about the systems that elevated their choices to law. Cecil Sharp's "sanitised, classist, racist and very, very male" vision of morris dancing didn't emerge from nowhere — it was institutionally enforced, materially supported, systematically preferred over alternatives like Mary Neal's more inclusive approach.

Those systems, we now realize, were the first AI: not silicon, but class, access, and institutional gravity. Our Folknet — ridiculous, exhausted, desperately clinging to its preferred timelines — is, in hindsight, an unintentional homage.

The Municipal and the Meta

MacBeth's most provocative insight is her concept of "municipal folklore" — the way city councils unintentionally create new folk practices through civic rituals, parades, and charter days. This is exactly what we were satirizing with our mechanics of Canon Weight and NPC awareness: how cultural systems ossify through repetition, funding, and institutional authority, even when they pretend to be grassroots.

The difference is that she traces this process with forensic care, while we turned it into a punchline about temporal interlopers creating the variants that plague someone else's session. Both approaches arrive at the same recognition: that "tradition" is often a negotiated artifact of power, chance, and infrastructure.

What Gets Lost in Translation

Where both works might be accused of minimization is around the structural forces that decide which fragments survive. MacBeth gestures toward the violence of archival selection — whose stories are told, whose are silenced — but sometimes wraps it in the romantic intimacy of the "collector's eye." Our game sidesteps this entirely in favor of playfulness, treating systemic bias as a mechanics problem rather than a historical wound.

Neither fully grapples with what your user preference points toward: that individuals often lack the leverage to meaningfully challenge these systems. The collector with a shed full of objects, the game designer with a satirical framework — both are working within constraints they didn't create and can't fully control.

What Comes Next

So what do you do when your joke grows teeth? You lean into it.

If Electric Eden began as a satire about the impossibility of fixing a song, The Lost Folk reframes it as an invitation: not just to break things, but to look more closely while you're doing it. To remember that every time you intervene — in a ballad, a custom, a collection — you're standing on a scaffold built by someone else's labor, someone else's devotion, someone else's grief.

Maybe that's the quiet sequel we didn't know we were writing: a more grounded, more attentive Electric Eden, one that still delights in disruption but carries with it the humility of knowing that someone, somewhere, has been tending this fire for a very long time.

The convergence wasn't coincidental. It was inevitable. When the cultural air is thick enough with an idea, multiple hands reach for it simultaneously. MacBeth reached with archive gloves and a careful eye. We reached with dice and deliberate irreverence.

Both of us were trying to say the same thing: tradition is not a museum piece. It's an ongoing conversation between memory and possibility, and everyone gets to speak.