Behind the Wheel

A Gentler Systems Analysis of Traffic Safety in Oregon

Yesterday, Oregon woke up to a strange sort of compliment.

Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety released their annual “Roadmap of State Highway Safety Laws” and put Oregon at the top of the heap. On paper, we were the traffic-safety honor student: strong seatbelt rules, solid child restraint laws, motorcycle helmet requirements, impaired driving provisions, graduated driver licensing, and more. The state scored near the top for having the “optimal” set of laws on the books.

If law were destiny, you’d expect Oregon’s roads to feel like a Subaru ad: safe, sensible, dog tested and parent approved.

Instead, our motorists drive like Huns on the way to sack Gaul: People treat crosswalk timers as countdowns—the zero doesn’t mean stop, it means “floor it before anyone tries to cross." Lane discipline is a wishful thought; zippering is for trousers. Pedestrians step into intersections with the wary body language of prey animals while virtually invisible between paltry streetlights and the local commitment to head-to-toe black. Freeways become low-key demolition derbies every time it rains, which is most of the year. The median highway speed is the posted limit plus fifteen, maybe twenty, depending on the collective's appetite for destruction.

The lived, embodied reality of Oregon traffic is not “model state for safety.” It feels much closer to “we have made a blood pact with entropy, and entropy called shotgun.”

That’s where Stafford Beer walks onto the Lake Woebegon soundstage with one of his most quietly devastating lines:

The purpose of a system is what it does.

Not what it says it does. Not what its designers wish it did. What it actually produces, reliably, over time.

If Oregon has “the best laws,” but still produces elevated deaths, weird enforcement patterns, and a steady stream of fines that function like regressive taxes, then maybe the traffic safety system isn’t primarily about safety after all. Maybe the system’s purpose is hiding in plain sight in its outcomes.

Let's take a look shall we? Gently, but without blinking.

When Rankings and Reality Don’t Match

The ranking is not fake. Oregon really does look great on paper.

We check all kinds of boxes: primary seatbelt enforcement, universal motorcycle helmets, ignition interlocks for repeat DUI offenses, open container laws, child endangerment enhancements, and so on. The checklist is long; the green ticks are satisfying.

But when you set down the report and look at what the roads actually produce, the picture changes.

Over the last decade, Oregon’s traffic fatalities rose much faster than the national average. Per-capita deaths sit above the U.S. mean. Per-mile-driven deaths are higher than they should be for a state with our legal framework and our “progressive” self-image. Rural roads are especially lethal, clocking in at more than twice the fatality rate of urban streets. The laws are platinum, the outcomes are bronze.

It doesn’t mean the laws are useless. It means they are operating inside a larger system whose real purposes—its true norths—are not necessarily aligned with safety.

To see those purposes, we have to stop asking what the system ought to be doing and simply watch what it does.

A Simple Picture of a Complicated System

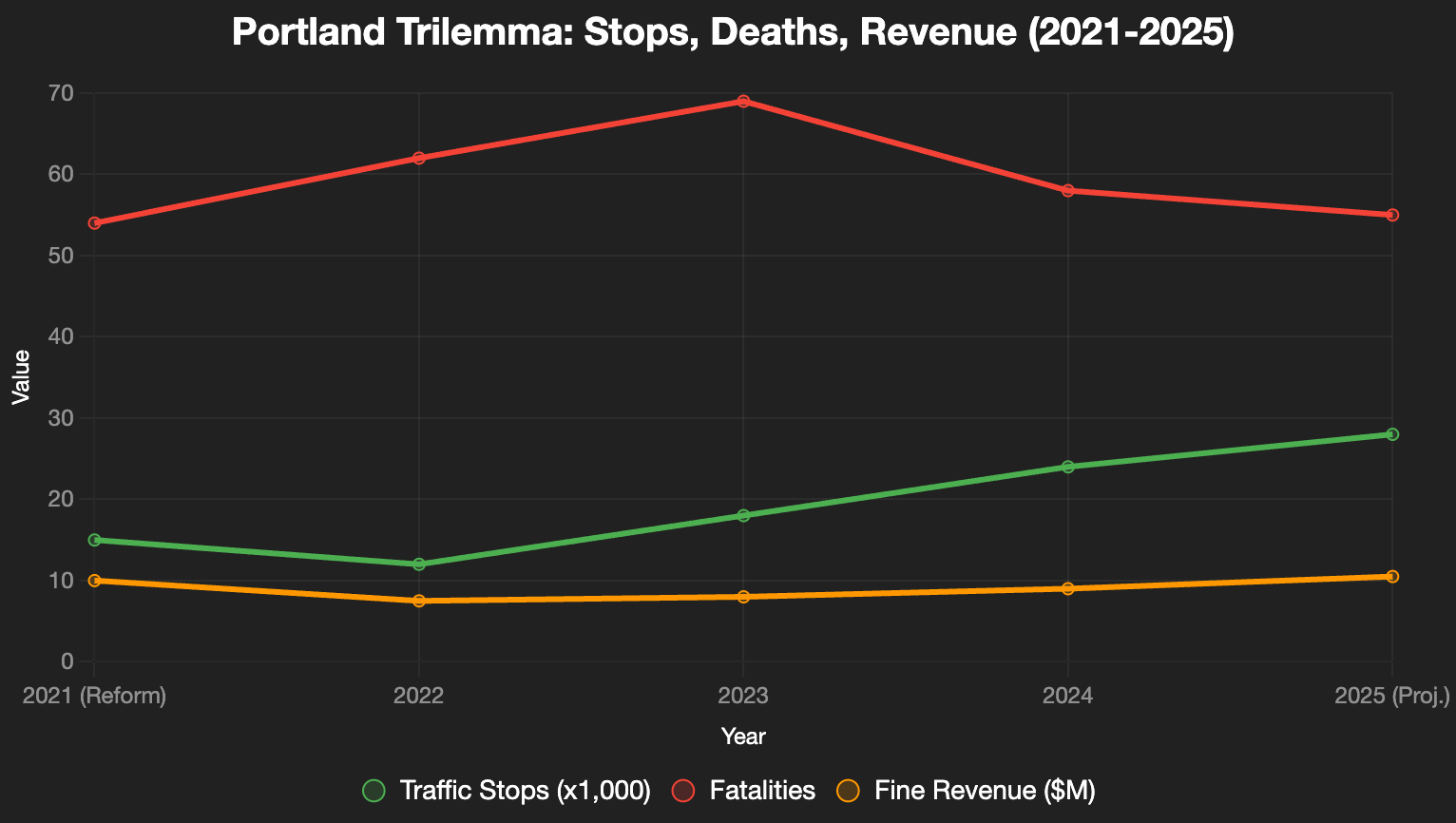

Imagine a chart with three lines running from 2021 to 2025 in Portland:

- Green: the number of traffic stops.

- Red: the number of people killed in crashes.

- Orange: total revenue from traffic fines.

The picture looks roughly like this:

- In 2021, you have a baseline year: a certain volume of stops, a certain number of deaths, around ten million dollars in fines flowing into city and court budgets.

- In 2022, reform arrives. After years of data showing racial disparities in stops and searches, and pressure during the 2020 protests, Portland scales back many low-level, discretionary traffic stops. Equipment violations and minor infractions aren’t prioritized. Stops fall.The result:

– Stops go down.

– Revenue from fines drops by about a third.

– Fatalities… go up. - In 2023, the trend hardens. Stops remain relatively low. Revenue stays in a painful trough. Deaths peak at their highest level in years.

- At that point, the system flinches. Whatever the intentions of the reform, three things are now true at once:

– People are still dying at unacceptable rates.

– Racial disparities haven’t disappeared.

– The city is losing several million dollars a year in predictable revenue.

So in 2024 and into 2025, the green line turns sharply upward. Portland ramps up enforcement again. Stops increase well beyond the reform low point. The orange line follows: revenue returns toward—and then slightly above—its old levels. The red line edges down, but not dramatically: deaths decline from the peak, yet remain higher than in the pre-reform year.

From a systems perspective, you couldn’t ask for a clearer confession.

The variable the system moves most aggressively to protect is revenue. The knob it turns to do that is stops. Safety improves or worsens at the margins, but rarely enough to drive decisions on its own.

Whatever the stated goals, the system behaves as if its primary purpose is stabilizing a stream of money. Safety gets managed. Equity gets aspirational memos. Revenue gets results.

POSIWID in the Rearview Mirror

Beer’s line lands a bit differently once you’ve stared at those three curves for a while.

If the purpose of a system is what it does, not what it says, then we have to admit some uncomfortable things about our current traffic regime:

- It consistently produces fiscal stability for municipalities that have baked fine revenue into their budgets.

- It intermittently produces safety improvements, especially when technology or targeted enforcement line up with where the danger actually is.

- It reliably produces inequity, because discretionary enforcement and flat fines fall hardest on those who have the least money and the least room to dodge attention.

None of these outcomes require villains.

Legislators can be entirely sincere in their desire for safer roads. Police officers can be genuinely committed to fairness. Administrators can be doing their level best to keep the city solvent. Advocates can be pushing for more laws in good faith.

But sincerity does not alter feedback loops. Intent does not rewire incentives.

A system that funds itself through tickets will, over time, find ways to maintain the ticket stream. A system that gives officers wide discretion over who to stop, where, and when will, over time, reproduce the same racial and economic patterns as the society around it. A system that measures success by revenue and citation counts will, over time, drift away from the messy, lagging, multifactor reality of actual safety.

That’s POSIWID: not an accusation, but a description.

The Trilemma: Safety, Equity, and Revenue

Portland’s five-year arc reads like a lab experiment in what happens when you pull too hard on one corner of a three-way tradeoff.

You can imagine three competing goals:

- Safety – fewer people injured or killed.

- Equity – fewer disparities in who gets stopped, fined, and searched.

- Revenue – dependable money for courts and city services.

In 2021, the system muddled through: middling safety, significant inequities, steady revenue.

In 2022 and 2023, the city tried to optimize for equity. It reduced discretionary stops, particularly for low-level violations that historically landed disproportionately on Black drivers and low-income neighborhoods. Disparities narrowed. Encounters dropped. But the other two vertices of the triangle wobbled:

- Revenue fell sharply.

- Deaths rose.

By 2024, the system had had enough. Under political and fiscal pressure, the priority shifted back toward revenue and safety. Stops surged. Automated enforcement expanded. Some serious crash numbers improved. Disparities began to creep back.

What almost never happens is all three vertices improving at the same time. Under current design, you get at most two:

- Safety + Revenue (at equity’s expense), or

- Equity + Safety (at revenue’s expense), or

- Equity + Revenue (with safety getting worse).

The ranking we started with—the one that crowns Oregon for having “the best laws”—does not measure this trilemma. It mostly counts how many boxes are ticked on a policy wishlist. And checklists are terrible at capturing how a complex system behaves when those policies meet budgets, roads, habits, and history.

Everyone’s Doing Their Job. That’s the Problem.

One of the cruelest things about systems is that people can be doing exactly what they’re asked to do, exactly how they were trained to do it, and still end up contributing to outcomes nobody wants.

- Budget officers are told to balance the books; fines are one of the few levers they can pull without raising taxes.

- Police administrators are told to “do something” about rising fatalities; traffic enforcement is one of the visible tools they control.

- Officers are dispatched to where they’re told to go; those places often correlate with where people are already over-policed.

- Legislators are graded on whether they passed “strong” laws; adding more infractions is an easy way to show action.

- Judges are told to apply fines consistently; flat dollar amounts are simple, even when they’re regressive.

Each link in that chain makes a kind of local sense. Put them all together, and you get a system that:

- balances budgets on the backs of people least able to pay,

- tolerates a higher level of traffic death than it publicly claims to accept, and

- quietly undoes equity reforms while restoring revenue flows.

Not because anyone sat down and wrote “this is the plan,” but because this is what the structure rewards and protects.

The purpose of the system is what it does.

So What Would It Take to Change the Purpose?

Once you accept that the “real” purpose is expressed in behavior, not branding, the next question isn’t “How do we make people try harder?” It’s “How do we change what the system finds easy, and what it finds painful?”

There are a few patterns from other jurisdictions that at least point in a different direction.

One is decoupling revenue from enforcement. If cities don’t get to keep the money from fines—or only get a small, capped portion—the incentive to use tickets as back-door taxation weakens. In some pilots elsewhere, routing fine revenue to a state transportation fund or a general pool, rather than directly to local coffers, has reduced the pressure to write tickets for budget reasons. Where this has been combined with income-based fines (so a wealthy speeder pays more than a broke one for the same behavior), both equity and deterrence improved.

Another is deploying enforcement where the deaths actually are, instead of where the people are easiest to pull over. When departments stop prioritizing broken taillights on well-lit arterials in favor of speed and DUI checkpoints on rural highways and known high-crash corridors, total crash and injury rates tend to fall faster. The overall number of stops doesn’t necessarily go up; they just become more targeted and more aligned with risk.

A third is automation with guardrails: speed and red-light cameras that eliminate officer discretion, paired with sliding-scale penalties and strict limits on how revenue can be used. Cameras on their own can easily become pure extraction; cameras in a system that has been financially decoupled from fines can be a safety tool.

And finally, there is transparent accountability for the small number of officers who produce the largest share of discretionary stops and searches. In many departments, 10–20% of officers account for a hugely disproportionate share of racial disparities. Identifying and intervening with that group doesn’t fix the structure, but it can address some of the worst emergent behavior.

None of these changes are soft. They threaten budgets, habits, union power, political comfort. That’s exactly why POSIWID is useful: it tells you where resistance will be fiercest by pointing to the outcomes the system currently defends.

If revenue is the quiet god of the current arrangement, then any reform that doesn’t design a new god—a new way to fund what needs funding—will be fought, delayed, or quietly undone.

A Gentle Sort of Clarity

It’s tempting to end on a note of either outrage or resignation. Outrage at the thought that we’ve built a system that treats deaths as the price of doing business and fines as a line item. Resignation at the sense that the machine is too big to budge.

But our bias is toward a third option: gentle clarity.

Gentle, because everyone inside this system is, on some level, doing their best within the constraints they can see.

Clear, because the constraints themselves are cruel, and pretending otherwise doesn’t save anyone’s life.

Beer’s little aphorism is often read as a scolding. It can also be read as an invitation.

If the purpose of a system is what it does, then changing the purpose isn’t about writing better mission statements. It’s about changing what it does.

Taking money out of the enforcement feedback loop.

Putting bodies where the danger is, not just where the drivers are easiest to ticket.

Letting data show us which reforms stick and which ones the organism rejects.

Accepting that safety, equity, and revenue can’t all be maximized at once with the current wiring.

Rankings and report cards will keep telling us that Oregon is a model state. The roads, and the chart of stops/deaths/revenue, will keep telling us what the system is really optimized for.

If we want that purpose to change, the work is not to argue with the ranking. The work is to rewrite the ledger the system uses to decide what counts as success.

And then watch, very closely, what it does next.